By Amreeta Lethe

Our educational institutions have not updated their curricula in decades, wilfully ignoring (and sometimes erasing) the contributions of women in literature. Is it any wonder that our mass media marketing messages completely miss the plot?

In the first couple of years of my undergraduate degree, when classes had been forced to move online due to the pandemic and there were a scarce few ways to meet and keep up with one’s classmates (which, admittedly, I did poorly), I had made a reputation for myself as the student who picked fights with their professors in nearly every course I was in.

It was always the same fight, too, if you could really even call it that. My professors and lecturers would share with us their department-approved – and sometimes dictated – course outlines, and I would ask them where the women were in their syllabi. The question had been asked, answered, and debated so often and in so many courses that I used to be able to categorize the responses according to the arguments made, although I can’t remember them all anymore.

Responses would usually begin with a pause, a laugh, or some vague appreciation of the question signaling a crumb of critical thought, after which, depending on the kind of course, there would be some sort of an explanation.

The best of their times?

The historical era-focused courses – your Romantics, Victorians, and Restorations (not to mention most of the Intros to) – probably had my least favourite response: “The authors we’re reading are simply the best of their times, or those who best represent the literary era we’re discussing.”

Ah yes, the literary canon. If pressed further on the criteria upon which these men and their works had been so dubbed, or what the women had been up to back then, I would usually be hit with a defeated “Well, we can’t possibly teach every author from that period” or “Take it up with the people who decide your texts.” God forbid the discussion take up too much of the class time; there were, after all, a trimester’s worth of texts to finish.

There were rarely discussions on how the literary canon had been decided or who had decided on it in the first place; of course, historically, it was always men of very particular race, class, and social standing. And there were rarely, if ever, discussions on where the women were in such times and what they had been writing, let alone attempts to deviate from the usual lesson plan to look into it.

In the worst of cases, we received half-hearted explanations about how most women did not have the means to be writing all those centuries and decades and years ago – either they were not writing novels when novels were the new, hottest thing on the block, or they wrote far too little about the truly important, transcendent matters of life – leading up to thinly veiled implications that what they did write was probably not good enough for the canon being taught.

We never discussed why all the literary eras worth basing entire courses on seemed to have been ushered in by men, or why women’s writing never elicited the same, course of literary history altering response.

And so the women led no movements. And so they did not write.

The canon is male, by default

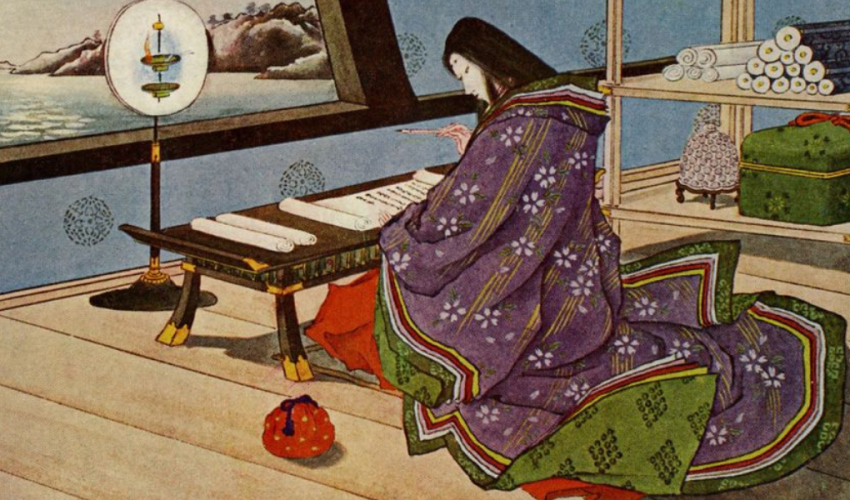

The ever shifting goal-posts never seemed to stay still for long enough for women to be included in the abundance of texts being taught. Who cared if the first recorded author, poet, and biographer in the world was an ancient Mesopotamian High Priestess, or that the world’s first novel is popularly credited to a Japanese woman?

Neither was a white, cishet man writing about the war or himself, so what did an English department care for them? But that is at least eight other cans of worms, a couple of which we might get to later in this piece. No promises.

The worst of the lot was probably a couple of courses I’d taken on Modern American drama and contemporary literature in translation. Still no women. What could I even ask anymore? Were women writing 50 years ago? Are women writing now? Apparently not.

Quite the existential crisis there. Each trimester, I complained to my mother, an English Lit major herself, about the “fights” I’d been picking, and told her I hoped it would change with higher level courses. Maybe when we got further enough into literary history, things would change. But here we were, with no Modern American or contemporary writers who were women.

My instructors for these courses offered no excuses; sometimes they explained, and at others they were apologetic, empathetic towards the indignation I felt. But it is also difficult to blame the issue on individual members of the faculty, especially when they themselves are often teaching courses in isolation, and may not know about or have enough access to the syllabi of other courses to notice the trend of leaving women out of numerous consecutive courses.

The dearth of women in the curriculum is emblematic of greater systemic issues, both within academia and without. Even now, when I try to Google the authors whose existence I keep yelling in class about, I am flooded with results titled with notions of a “female canon” or several that can only stand in opposition to the existing canon – which is certainly not genderless, so then, by default, is it male?

Real inclusion is still a fantasy

Then there is the issue of optics. Because it is popular and fair game now to present as liberal, especially among institutions and corporations, and institutions run by corporations, the aesthetic value of being saviors and allies of the oppressed is far too marketable to resist. Real inclusion remains a far-off fantasy, however.

After all, it is far easier to arrange seminar after seminar – that can be publicized, no doubt – to wax poetic about some depoliticized and defanged version of feminism, and far easier to dress in purple and hand out flowers to colleagues on International Women’s Day, than it is to develop structures that accommodate women and their needs instead of making them adjust.

And so the canon does not shift, and the curriculum is not deviated from. And so the women do not write.

There is no easy way to resolve such an issue that does not call for the dismantling and decentering of the literary canon, and a complete overhaul of what is taught and how. However, gender itself cannot be a sole focal point for such an overhaul, considering that women are not a monolith of some kind with homogenous “women’s struggles” that can be solved using a one size fits all solution.

Patriarchal notions do not exist in a vacuum, and are inextricably tied to cisheteronormativity, capitalism, and class struggle, indigeneity, and other forms of minoritization – oppressions as manifold as one’s intersections. And so, any attempt to include rather than merely appear inclusive is bound to take radical structural change.

It is important to understand that inclusion must go beyond tokenistic representation, and thus cannot be caught up with merely ensuring the presence of more women and people from other underserved communities for the sake of checking diversity boxes or filling quotas.

I expect little from bigshot companies and corporations which, every year for IWD, spend millions to then come up with the blandest, most tired ideas for ad campaigns. Ah yes, women can handle both the office and the household, saying nothing of the decades of their lives spent doing unpaid domestic labour. And yes, women – who are, for some reason, all “bhabis” – do deserve to get free coffee upon bringing their “bhaiyas” to your overpriced coffee shops, saying nothing of how, even a cup of free coffee on IWD necessitates the presence of a man for some inexplicable reason.

Nafisa Tanjeem recently published an excellent piece in New Age titled, “On corporatised, NGOised, and lifestyle celebration in Bangladesh” for IWD 2023, delving into how these annual ad campaigns are done merely for sake of optics, severed from women’s struggles for liberation of any kind.

But universities – universities ought to be different. Humanities departments in particular need to sort out their identity crises and priorities of wanting to be radical and marketable simultaneously, and failing to do either well enough.

Amreeta Lethe is the Editor in Chief of The Dhaka Apologue