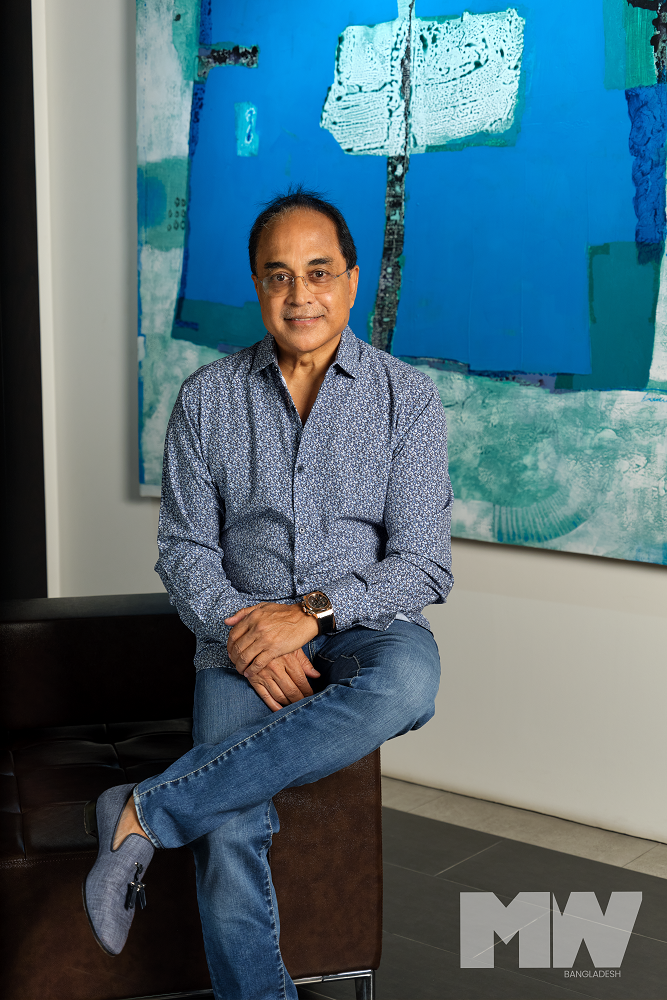

Industrialist, freedom fighter, philanthropist, and patron of the arts, to name just a few. It is not an exaggeration to say that one needs a bookmark when listing the diverse roles and responsibilities Anjan Chowdhury has shouldered in his lengthy, storied career. The MWB team made it over to his Banani office one rainy morning for a conversation and insights from this polymath from Pabna

By Sabrina Fatma Ahmad

The late Samson H Chowdhury left some big shoes to fill. The visionary who took a Tk5,000 loan from his father to start a small pharmaceutical company with three friends in 1958 eventually grew it to a multi-billion-dollar conglomerate that encompasses everything from drugs to food to media and more. The apples falling from this tree would have to roll very far to outrun its shadow.

“I’ve always been changing my mind about what I wanted to be,” his youngest son Anjan Chowdhury jokes, when asked about what it was like to grow up in the Square family, adding that aviation and architecture had the highest appeal for him. Although he got to try out both (he is currently President of the Aviation Operators Association of Bangladesh, and while he didn’t pursue architecture, he has designed a building), the young boy who would one day take the reins as Chairman and Managing Director, had his eye on the ball from the very beginning. “It was a brilliant childhood,” he recalls, adding that he grew up in Pabna, near the banks of the Ichamati river, in the bosom of a large, but close-knit family that included his grandparents, paternal uncles and their wives and children, along with his own parents and siblings. He remembers his father as always on the move, traveling to Dhaka for work, and frequently flying off to West Pakistan, which at that time was where all the major administrative work used to happen. It was his mother who nurtured her three sons and daughter, and also doled out discipline as necessary. His father’s approach, Anjan Chowdhury recalls, was to explain with logic. “Honestly, when I was younger, I would have preferred a slap or two over the expressions of disappointment” he jokes.

It was a balanced childhood, with emphasis on discipline and routine, but with plenty of time for curiosity and play, creating a strong foundation that would carry him through his life, and providing him with valuable lessons to draw from.

Lesson One: Discipline is everything

That gentle childhood is a far cry from his present reality. In the Square Group alone, he manages more than 31 ventures of the Group in the capacity of Chairman & Managing Director respectively. He is also associated with various trade bodies, professional and social organizations outside of the family business. He is currently President of ATCO (Association of TV Company Owners), served two terms as Chairman of Micro lndustries Development Assistance and services (MIDAS) and is currently a Director, and Chairman of Society for the Promotion of Bangladeshi Art (SPBA) and President of Annada Gobindo Public Library, Pabna. And we’re not even done listing his full portfolio.

How does he manage his time and energy not just to participate, but lead? He credits his father with being a role model for discipline. “He’d be up and ready and at work before any of us” he recalls, saying punctuality was paramount. Anjan shares with us anecdotes of colleagues and journalists who learned the hard way just how important it was to show up on time. He credits his mother Anita Chowdhury – lovingly remembered by the company as ‘Square Mata’ – with fostering a work culture based on dignity, equality and cooperation. “I delegate responsibilities to my colleagues at various levels, and make them stakeholders in their work. While I am around to guide and to support, I don’t believe in micromanaging them. When they ask me what happens if they make mistakes, I tell them it’s okay to make mistakes as long as you learn from them.” This frees up his plate for his interests outside of the Square Group, of which there are many, and we decide to dig in.

Lesson Two: Be a patriot

Of the many transformations Anjan would witness in the country, the Liberation War was the first major paradigm shift. He is a freedom fighter, having received commando training in Dehradun cantonment in India and served in the Bangladesh Liberation Force. He thinks of this time as a ‘loss of innocence’, having witnessed his comrades dying. “We’d never seen a gun in real life before that!” he exclaims.

“The growth we have seen post 1971 would have been impossible without Liberation. We would simply not have had the freedoms or opportunities that we enjoy today. It was a privilege to be part of the effort in achieving that Liberation, and now that we have a free country, it is our responsibility to nurture it”

He doesn’t dwell on the darker details however, seeing it as a blessing to have had the opportunity to be part of the movement that liberated his beloved country. Shortly after the war, he left the country to pursue higher studies at the University of South Florida. “It gave me a sort of detachment from the horrors of the war, you know” he explains, acknowledging that this was a privilege, when he has seen many of his contemporaries who stayed behind who remained stuck on the past, unable to move forward or escape the trauma. For Anjan Chowdhury, it would not to do to remain stuck when his country needed him to move forward. “I tell my colleagues you are contributing to the nation through your activities. You feel good about it. You are in a noble profession. You are not only supporting your families, fellows and colleagues. You are also supporting the nation. This is the satisfaction I have that I share with my colleagues.”

His time in America taught Anjan about efficiency and dignity of labor. “There is no job that’s higher or lower than others” he says, saying this is a principle he has taken to heart and the culture within his organizations is to treat everyone as equals, regardless of station.

In fact, something that would become a motif for the entire conversation is that he never assumes credit for any of his successes. A true team player, he will talk excitedly about his vision, but be very liberal with giving kudos to everyone involved in realizing that vision, making it a shared success – a rare quality in Bangladeshi leaders.

Lesson Three: Quality is key

Anjan Chowdhury has produced many feature films, short films, telefilms, single dramas and drama serials. He received the National Film Award 2010 as Best Producer in the year 2011 for Monpura, repeating his success in 2020 for Bishwoshundari, and he also had the pleasure of watching Hawa, a film he produced under Sun Music and Motion Pictures Ltd, reach dizzying heights of international acclaim.

His foray into film stemmed from a sense of dissatisfaction, he tells us. Being tasked with launching the Meril brand, he had a chance to travel throughout Bangladesh. “I’d be on the road, chugging cans of V8 juice that served as my breakfast and lunch, before stopping at a hotel or rest house for the night in whichever district we were visiting, to grab my first actual meal and get a night’s sleep before waking up the next morning and doing it all over again. “My father had always insisted on quality, and this is what he had built the Square reputation on, so having that was a privilege, it was still a challenge to get people to get on board this new brand. There were so many clients who wanted the “pay later” option, which we were solidly against.” This practice frustrated Anjan Chowdhury, but not as much as the quality of existing advertisers and marketing services responsible for building the brand story. It was this sense of dissatisfaction with what was available at the time that made Anjan decide to take matters into his own hands. He started making the ads himself, and this was a natural progression from writing and making ads to writing and producing films, dramas and more. He produced Kobori Sarwar’s directorial debut Ayna in 2006. Eventually, his deep involvement in films and television led to the establishment of Maasranga Television in 2009.

Given that Monpura, Hawa and Bishwoshundori received critical acclaim as well as financial success, we were tempted to ask how Anjan Chowdhury measures his films. His answer was a modest “I cannot take credit for their success; it is all due to the skill of the director and the team. I will choose a project to work with if I like the story, and a director to work with if I like their work, but once I do, I don’t interfere with their vision.”

Lesson Four: Education is an investment in the future

As well as being a Regent Board Member of Pabna Science & Technology University since its inception, Trustee Member of the Education, Science, Technology and Cultural Development Trust (ESTCDT) of lndependent University of Bangladesh, Anjan Chowdhury is Chairman of Society for the Promotion of Bangladeshi Art (SPBA) and President of Annada Gobindo Public Library, Pabna. He contributed to the establishment of ASTRAS Municipal Primary High School, Square Kindergarten and Square High School and College. He founded Dishari Computer Training Institute which is focused on developing IT skills from a secondary level among poor and meritorious students. It is pretty apparent that he highly values education.

“It began with me wanting to establish a school in my hometown Pabna, where the teachers would not be involved with coaching after classes. All the teaching should happen during the designated school hours. Also, if the staff members from our companies could be subsidized, they could enroll their children in the school without there being any of the social comparisons you unfortunately see in other private schools, then it would provide an equitable learning environment for all the students.” He reports with some pride about the success of the school, although he is quick to place all the credit on the shoulders of the principal of the institution. “I can’t personally go give a lot of time to any of these educational establishments, but I have been very lucky to find people who are really doing a good job and executing these plans well” he adds.

Anjan does admit to a level of frustration regarding the overall quality of education in Bangladesh, contrasting with the kind of education he received in his youth. He believes he was blessed with teachers for whom the job was a vocation and a calling, rather than the means to economic survival, and that made a big difference. He is firmly opposed to the idea of coaching centers and cram schools, and believes the students’ time would be better spent in libraries, in watching good films, in practicing sports, rather than finishing in a coaching center what should have been completed during the school hours. He believes quality education should be accessible to all, because students are an investment in the future, and is of the opinion – which he admits may be considered controversial in some circles – that private universities should be free from politics.

“In education, we need to focus less on finishing a set curriculum, and more on the knowledge we are gaining. We need to understand what the world is looking for, what the market demands. What good is a degree if you don’t have the skills that your future employer is looking for?”

Lesson Five: Don’t fear the future

Our conversation went over to more of Anjan Chowdhury’s “extra-curriculars” because of course the man has also achieved much in the fields of music and sports. Anjan Chowdhury is a sports enthusiast and received the National Sports Award 2009 from The Ministry of Youth & Sports for his contribution to the development of sports in Bangladesh. He is Vice President of Bangladesh Olympic Association (BOA) and a Councilor and Former Vice President of Bangladesh Football Federation (BFF), Councilor of Bangladesh Cricket Board, Director of Abahani Limited (Football Club). He founded and lead the Pabna Pirates Football Club and Pabna Pirates Cricket Club, and was formerly a member of the Finance Committee of Kurmitola Golf Club (KGC), a former Executive Committee Member of Bangladesh Golf Federation, Adviser of Pabna District Sports Association and Samson H Chowdhury Tennis Complex, Pabna.

As I pause to catch my breath just running through his sports involvements to ask about his overview of the sports situation, he heaves a sigh and admits there is a lot of room for improvement. “Sports happen at a district level, and are under the purview of someone called the ‘Krira Shikkha Officer’, and I am not sure exactly what these people are doing, because where are the players? What’s the point in building stadiums which will only end up as grazing grounds for cattle because there aren’t any players?” He elaborates that there needs to be better recruitment practices, training, and overall oversight if we are to see any real improvement. “And I agree with you that we should be investing a lot more in our women’s [cricket and football] teams. They’re doing well; they deserve better from us.”

“It gives me immense pleasure to see the growing awareness of and appreciation for the wealth of artistic talent in our country. A few decades ago, it was foreigners who recognized the fantastic art we were producing, and snapping them up at unbelievably low prices. We now have a healthier pool of Bangladeshi buyers and collectors who are now investing in our art, so our artists are getting both the recognition and the compensation for their craft from their own countrymen”

He brightens up more when we talk about music. Anjan Chowdhury is the President of Bonomali Performing Arts Center, Pabna, and initiator of the hugely successful Dhaka International Folk Festival, which started in 2015. “First and foremost, my hometown is in Pabna which is a cultural hub, very close to Kushtia, which is the origin of Baul music. I grew up listening to the most fantastic folk music. My parents were both great enthusiasts.

The idea of Dhaka International Folk Fest started from the desire to have a folk music festival on an international scale, which would include folk musicians from other countries. We wanted to give international recognition to local musicians through this initiative. But how to do this? Instead of bringing the local musicians to foreign countries, I thought about bringing the foreign talents here so they can perform alongside us and let them ‘discover’ our local talent. A big venue like the Army Stadium, security guaranteed by our company. It was a great way to promote our music, and also create a better brand for Bangladesh.”

The Dhaka International Folk Festival is currently on hiatus since Covid, and also with respects to the current economic situation. Anjan Chowdhury, who has been recognized by the Government of Bangladesh as a Commercially Important Person (CIP) since 2005 and one of the highest Taxpayers of Bangladesh since 2008 for his continuous contribution to the economic development of the country, explains the complicated taxes and funding issues involved in bringing the foreign performers into Bangladesh in the light of the ongoing dollar crisis.

This is the perfect segue to ask him if he is afraid of the future. He pauses thoughtfully before providing a cautiously optimistic no. “The whole world is in a crisis, this is true, but I have faith that we will pull through. We are extremely fortunate to be food-sufficient; because that would have made things much harder, and for this, we have to thank our farmers who have saved us time and again with the sweat of their brows. We are deeply indebted to them.”

Reflecting on the rising prices of essentials, he acknowledges that there are artificial problems created by hoarders, but also says that the consumers hold more power over the market than they realize. “Think about the insane prices of chilli peppers. If the nation as a whole decided to abstain from eating chilli peppers for one week, what do you think would happen to the prices?” He provides the example of food prices skyrocketing during Ramadan, a phenomenon unique to our region, whereas in other countries, festival seasons usually mean sales and discounts.

Final lessons

Our conversation ends with one of the communal lunches we have heard about; everyone seated together and enjoying a hearty meal without a thought to issues of hierarchy. We discuss Dhaka Diorama, and Anjan Chowdhury refuses to play favorites about his opinion of the artists. We talk about the future of art in general, and he is of the opinion that the perceived threat of AI taking our jobs is not an immediate concern, because humans are exponentially more creative than any existing algorithm; unlike many leaders of his generation, he does not view the future generations with suspicion or condescension. ‘Young minds work in ways we cannot even conceive of. We need to respect their perspective and listen to their ideas” he tells us.

As someone who has invested in practically every sector in Bangladesh, Anjan Chowdhury has much to be proud of. But the message that keeps coming across from him is the believe in the power of collective effort. At every stage, he has deflected praise to heap the credit on his partners and collaborators in each project. Every story begins with a dream that originated in his beloved hometown of Pabna. Every philosophy pays homage to the life lessons he has gleaned from his parents and teachers. Any hint of pride that we see, is bestowed on the people he has worked with, be it the students in the schools he has established, the athletes in the sports clubs he has founded, the many artists and directors and musicians he has worked with, or even the visual artists whose brilliant canvases cover the walls of his office.

Though he will be the first to say he isn’t “that closely involved” with many of the initiatives under his watch, without a doubt it is perhaps a certain magnanimity of spirit on his part that has allowed him to achieve so much.