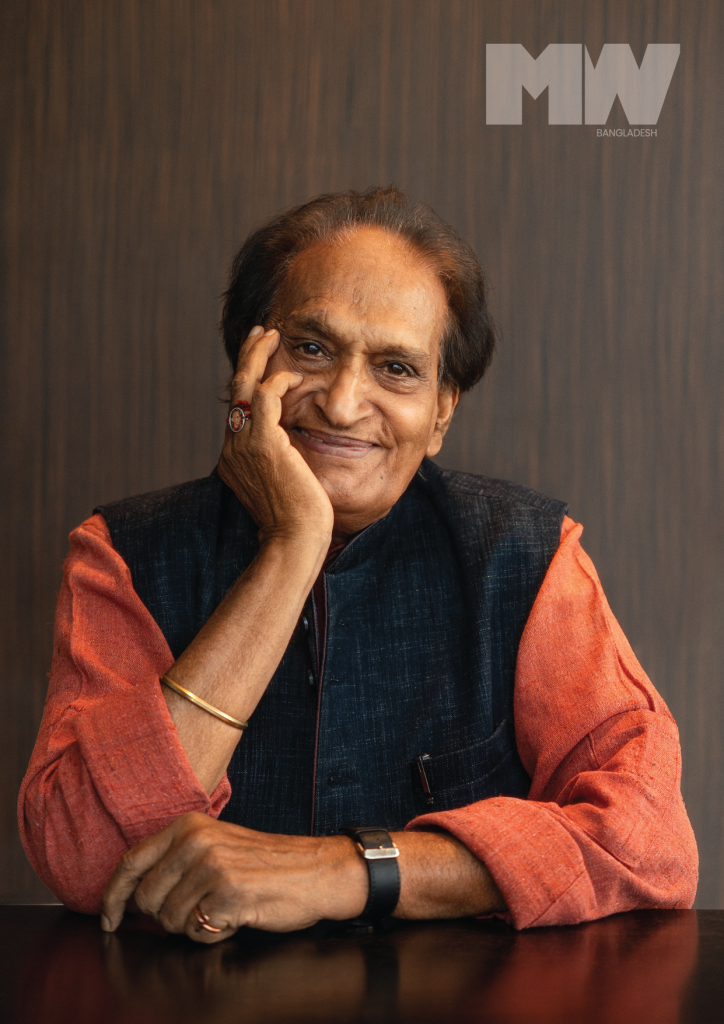

Celebrated photojournalist Raghu Rai on a new book and old memories

By Sabrina Fatma Ahmad

Interview by Neha Shamim

In the quiet pre-dawn hours, when the world is a soft murmur and the light is yet to kiss the horizon, there exists a realm where stories unfold in silence. Here, Raghu Rai weaves narratives not with words, but with the honesty of black and white, with the shades that lie between. His camera, an extension of his very soul, captures the essence of a nation in turmoil and triumph. From the haunting echoes of the Bangladesh Brutalities to the silent cries of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, Rai’s lens has chronicled the indomitable spirit of resilience and the poignant symphony of human emotions.

Through the eyes of icons like Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama, Rai has painted portraits of hope amidst despair, of serenity in the face of chaos. His photographs, a mosaic of life’s intricate tapestry, tell tales of the exodus of millions, the unspoken agony of refugees, and the valiant hearts of freedom fighters. Each frame a testament to the sacrifices etched into the annals of Bangladesh’s quest for liberty.

Awarded the prestigious Padmashree in 1972, Rai’s commitment to the unvarnished truth has garnered him not just accolades but a legacy that transcends time. His oeuvre stands as a visual diary of history’s most defining moments, a reminder that in the silence of a photograph, the echoes of history resonate the loudest.

The “Father of Indian Photography,” as Rai is often referred to, was in Dhaka recently, and spoke with MWB’s Neha Shamim about his new book, The Rise of a Nation.

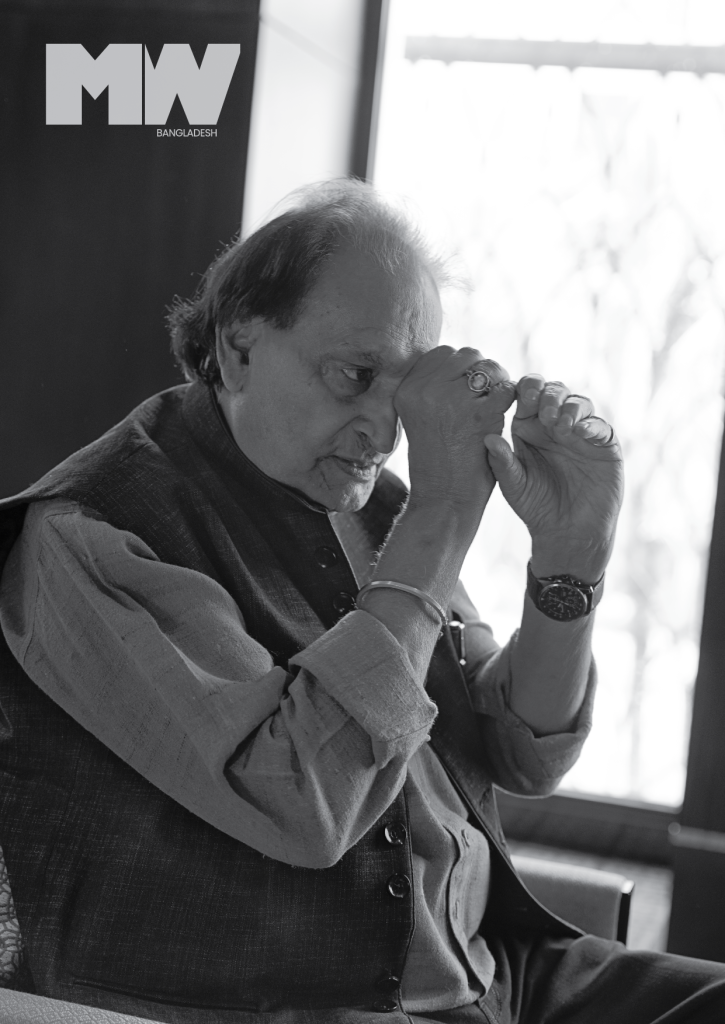

“I see a tall, dark man in his early 80s enter the sitting area,” says Neha, of her first glimpse of the man behind the legend. “He is wearing a red kurta with the sleeves folded, a dark navy blue sleeveless vest, and black pants paired with black leather chappals. People surround him as he enters the room. I think to myself, maybe that’s what fame brings – company.”

The interview

“Divine energy is always around us, so if you stay connected, you feel beautiful.”

What inspired you to take up photography?

“Accidents can happen in life; we all know that. My father was in the government’s irrigation department. He was head of the administration – the chief engineer. He also wanted his son to become an engineer. And in our times, we were not given choices; we were ordered to obey and to follow. I studied engineering and worked in Punjab in the government for a year, and didn’t really enjoy it. I came to Delhi, and I stayed with my brother S Paul, who was a well-known photographer.

My brother’s suitcase would be full of photographs, equipment, and hardly any clothes. His friends were always talking about lenses, cameras, other photographers and their images. It was as if nothing else existed. I watched this for a few months. Then one day, I decided to go with one of my brother’s friends to visit his village. Before going, on a whim, I asked to borrow a camera from my brother, who obliged, explaining how it worked and setting the exposures. I used it to take a few pictures. When my brother went to process these shots, he was impressed enough to send one to The Times, London.

In the mid-60s, The Times, London was one of the biggest newspapers. It used to carry a half-page photo of something unusual or ironic or strange. They paid a good amount for photos like this. The first photo I had taken with my brother’s camera was published in that section. Seeing my name with the picture, and seeing everyone’s reaction to seeing my picture in The Times, London, I thought this was something I could pursue. And that’s how I started taking pictures.”

Raghu Rai started learning photography in 1962 under his elder brother Sharampal Chowdhry (better known as S Paul), who is a photographer. In 1965 he joined The Statesman newspaper as its chief photographer.

“When I picked up the camera and looked through the viewfinder, all my energies were focused on what I was looking at. That was something very different for me. The camera was an instrument to have a closer look at life”

How did your parents react to this?

“My father, who wanted me to become a full-fledged engineer, was very disappointed. Somebody asked my father how many sons do you have? He said: “I had four sons, two of them have gone photographer” … [laughs] He was not happy. I worked very hard. In a year’s time, my photos were in papers, magazines, and he realized that what I was doing was important, and good.”

He saw the recognition that you were getting.

“Yes, exactly. In 1971, I was just 4-5 years old as a photographer, and my coverage of Bangladesh refugees, war, and surrender gave me so much importance, not only in India but in the world capitals. When I came back, it was for the first time that the Indian government honored a photographer. Because, you know, at that time, 10 million refugees had come into India, but Pakistan’s propaganda was such that nobody believed in the Indian government. And when I took my pictures around the world, and had exhibitions, I had great reviews. 10 million refugees coming into India became a reality for the rest of the world.”

Raghu Rai received the Padmashree Award, the fourth-highest civilian award of the Republic of India in 1972 for his work on Bangladesh’s Liberation War.

What difficulties did you encounter in the early years as a photojournalist?

“I didn’t believe in difficulties. I don’t think I was trapped in any psychological or personal implications of things that I had to do. I worked very hard. I won’t call it difficulty; competition gives you a new awareness. I played the game with my heart full, and put all my energies into it.”

How did you come to be assigned to cover the Liberation War in Bangladesh?

“I was the chief photographer with The Statesman newspaper in Delhi. Our head office was in Calcutta, where thousands of refugees were coming in from Bangladesh. Our editor felt that only the chief photographer could do justice to the situation. So I flew down to Calcutta, met the local reporter there, and we went straight towards the Jessore border from the airport. It was the month of August, and it was pouring. And I see, my God! Children, ladies, old women, walking in the rain. The magical thing maybe for me was, that it’s known that we as individuals, if we are creative people, we interpret our childhood memories somehow or the other. Now in my case, my childhood memories were just this – when the Partition took place, we came from Pakistan into India, into the borders, walking in the rain. I don’t remember much, but maybe in my subconscious, when I saw the same thing happening here in front of me, hundreds of people walking in, I could see myself as one of the boys walking in with them! That gave me the inspiration and energy to go on and capture every aspect, every suffering.”

Let’s talk about The Rise of a Nation.

“I had taken several trips, from August to December [of 1971] until the war was won. I went to Calcutta, I would go to the Manipur border, to the other borders to photograph the refugees coming in. Over the last few weeks, we went into Jessore, because the Pakistan army by then was withdrawing. Jessore was close to India, so they had already withdrawn from there, and had gone into Khulna and other areas. We went in from Jessore road into Bangladesh, photographing houses burning, women and children fleeing to safety, and all the while getting closer to the real emotional landscape of Bangladesh.

It was a very sad thing to see the Muktibahini – simple guys who just wanted to defend their nation – carrying old rifles, squaring off against the Pakistani army which had the latest weaponry given to them by America.

During the final weeks, as the Pakistani army began to withdraw, the Indian government was monitoring the situation, as Indira Gandhi, who was a tough prime minister, was concerned about the influx of refugees. I went with the army through the Khulna side. I was with the First Column, which means the tanks and soldiers that go for frontal attack. The Pakistani army was withdrawing and Indian army was advancing, guided by the Muktibahini. Both parties knew the landscape, which meant we stayed off the main road and moved along the railroad, under tree cover. There was an officer assigned to me from Delhi. The tanks were rolling, generating a lot of noise, the soldiers were moving. The Pakistani army fired an “air burst” which explodes in the air, raining splinters on the enemy. The first one that was fired was 250m away from us. The second, 200m, the third, 150m.

By 50m, I had already taken all the worthwhile shots I was going to get of our progress, and the attacks. Fearing that the very next explosion could injure us or worse, we packed up and ran for more than a kilometre in the opposite direction. There was a tea stall on the other side of the road where we stopped for tea and buns. My guide went to find out more information. After two hours we learned that several Indian soldiers had been badly wounded, but they had also managed to capture a few Pakistani soldiers who had been injured and left behind by their compatriots. I saw them being brought in on stretchers, and on the shoulders of our soldiers, and my major told me that this could have happened to us. That’s what I photographed extensively. I photographed the large abandoned building where some soldiers were holding a defensive position. I photographed that, the wounded soldiers – theirs and ours – some of the intriguing moments of suspense. We came back after that.

A few days later, the Indian Defence Ministry informed us that they were going to Dhaka, because the Pakistani army was about to surrender. I flew in with the army officer I had accompanied across the border. We arrived at 2:30 in the afternoon and it was an amazing experience. Things had turned around completely and the Pakistani soldiers were throwing down their arms and walking in with their heads bowed down in shame. Since it was winter, the light was decreasing fast. There were generals of both armies, and members of the international press. I photographed them all. I was sitting almost 2 feet away from Lieutenant General [Amir Abdullah Khan] Niazi and Lieutenant General [Jagjit Singh] Aurora. But Lieutenant General [Jack Farj Rafael] Jacob was the real true engineer of the surrender. General Niazi and the Pakistani army had sent a request to Indian Army that they would not surrender to General Jacob, because he was Jewish. The government of India accepted this, so General Aurora, who was the commanding officer in Calcutta flew in, and accepted the surrender, while General Jacob was there in the background.

When I was doing my book, I met with General Jacob, who was still alive, and he gave me the whole story. He says you know Pakistani soldiers were withdrawing. They largely withdrew to the Dhaka cantonment area, but wherever we went, we couldn’t find any Pakistani soldiers. There were 90,000 of their soldiers to our 3,000. Our advantage was in the fact that we had aerial reinforcements. General Jacob sent a wireless message to General Niazi, asking to meet with him alone. He had with him a draft of the surrender. I met with General Niazi alone in the office and let him know that he was surrounded, with our aircraft overhead. Niazi had his family and children with him in Dhaka at the time, and I assured him that no harm would come to them, or to his 90,000 troops stationed inside the Dhaka cantonment area as long as he surrendered.” General Niazi was incensed and refused to surrender, and General Jacob, who admitted he had been aware he had taken a huge personal risk by coming unaccompanied, left his counterpart alone with the draft for two hours, and by 5pm all the parties had gathered at the Suhrawardy Maidan for the formalities of the surrender. I had flown in by helicopter, and got photos of all the parties flying in by helicopter, of Gen Niazi looking humiliated, the signing itself, which took an hour to complete, Gen Aurora addressing the people. There was so much excitement, our Bangladeshi friends hugging. I took the pictures in slow shutter speed, racing against the waning winter light. Everything was over within a few hours.”

And a nation was born

“Absolutely. A victorious nation. There was so much joy and happiness. My story was complete. I did another small exhibition twelve years ago in Dhaka, with a small book. Then comes Durjoy Rahman, a great art collector, and he had seen my work, bought some of my pictures, and he decided to meet me in Delhi. He wanted to acquire some of the images which were an important documentation of Bangladeshi history. I was intrigued by this Bangladeshi man who had turned up after 45 years, and he passionately displayed so many emotions when viewing the materials, and when he said he wanted 100 images, we agreed to do a big book on the Bangladeshi refugees, the war, and I waived any fee for it. I had also been wanting to bring out a powerful, well-edited volume. Now that we have done it, I promise you it’s a visual history of Bangladesh Liberation War, and the price paid for it. It is a rare document. I wish I was grown up enough when we were fleeing Pakistan to India, that I could have done similar documentation for my own country, but now when I look at the whole experience, let me tell you, histories are written and rewritten, but visual history cannot be re-written. It is the final documented evidence of what happened. This is my offering to Bangladesh, and whosoever has seen this book just loves it. It is a great experience for me, and very fulfilling.”

“Histories are written and rewritten, but visual history cannot be re-written”

Raghu Rai left The Statesman in 1976 to work as picture editor for Sunday, a weekly news magazine published in Calcutta. Impressed by an exhibit of his work in Paris in 1971, Henri Cartier-Bresson nominated Rai to join Magnum Photos in 1977. Rai left Sunday in 1980, and worked as a picture editor and photographer at India Today during its formative years. From 1982 to 1991, he worked on special issues and designs, contributing picture essays on social, political, and cultural themes.

For Greenpeace, he completed an in-depth documentary project on the chemical disaster at Bhopal in 1984, which he covered as a journalist with India Today in 1984, and on its ongoing effects on the lives of gas victims. This work resulted in a book, Exposure: A Corporate Crime and three exhibitions that toured Europe, America, India, and Southeast Asia after 2004, the 20th anniversary of the disaster. Rai wanted the exhibition to support the many survivors through creating greater awareness, both about the tragedy, and about the victims who continue to live in the contaminated environment around Bhopal.

Rai has produced more than 18 books focusing on the culture and people of India, including Raghu Rai’s Delhi, The Sikhs, Calcutta, Khajuraho, Taj Mahal, Tibet in Exile, India, and Mother Teresa. His photo essays have appeared in many magazines and newspapers including Time, Life, GEO, The New York Times, Sunday Times, Newsweek, The Independent, and the New Yorker. He has served three times on the jury of the World Press Photo, and twice on the jury of UNESCO’s International Photo Contest.

Your contributions to the field of photography have earned you several awards and accolades –

“Including being a Friend of Bangladesh –”

Of course. Which of these achievements holds the most personal significance for you, and why?

“Every gesture brings richness and meaning, and is humbling. You don’t compare. At different times, every gesture brings warmth of expression.”

What legacy do you hope to leave behind through your photographic works?

[Laughs] I am an explorer who waits for the Divine to come in and help me. Whatever I have done, I’m sure, if it has a touch of Divinity, it will touch many hearts. How and where, it remains to be seen. When you work passionately as an explorer committed to the energies floating around you, you don’t look towards this end of the spectrum, at legacy and recognition. It doesn’t matter.”

Having experienced our war, and coming back to an independent Bangladesh today, how do you feel?

“Lots of love and warmth and connectivity. As I said. You call yourself Bangladesh. We call ourselves India. We are the same people. You practice Islam, mostly. When I walk into a church, I become Christian, when I step inside a mosque, I think as a Muslim. I am a Hindu when I step into a temple, and I am a Sardarji when I go to the Gurdwara. I have to receive that energy and purity of the people praying. If I don’t become part of them, I will not be able to receive it.”

The interview ends after many charming personal anecdotes, from his friendly competition with his brother S Paul and his good friend Kishore Parekh, to almost losing the negatives of his 1971 footage, to his personal opinion about Mother Teresa, about whose work he gushed at length.

“The interview ends, and for me, it becomes a cherished moment. I wish I could have tea with him and listen to more of his stories, but I decide it’s best to leave him with his peers,” says Neha Shamim. “I stand there in shock, realizing that the way Raghu Rai shared his stories wasn’t just an interview. It was a man who had seen everything – pain, poverty, love, death, genocide – and lived through it all, passing his wisdom to someone just starting out in life. It feels like he took me on a journey through time and then brought me back.”

- Sabrina Fatma Ahmadhttps://mansworldbangladesh.com/author/sabrina-fatma-ahmad/

- Sabrina Fatma Ahmadhttps://mansworldbangladesh.com/author/sabrina-fatma-ahmad/

- Sabrina Fatma Ahmadhttps://mansworldbangladesh.com/author/sabrina-fatma-ahmad/

- Sabrina Fatma Ahmadhttps://mansworldbangladesh.com/author/sabrina-fatma-ahmad/