Nasir Ali Mamun on photography, legacy, and the art of patience

By Ayman Anika

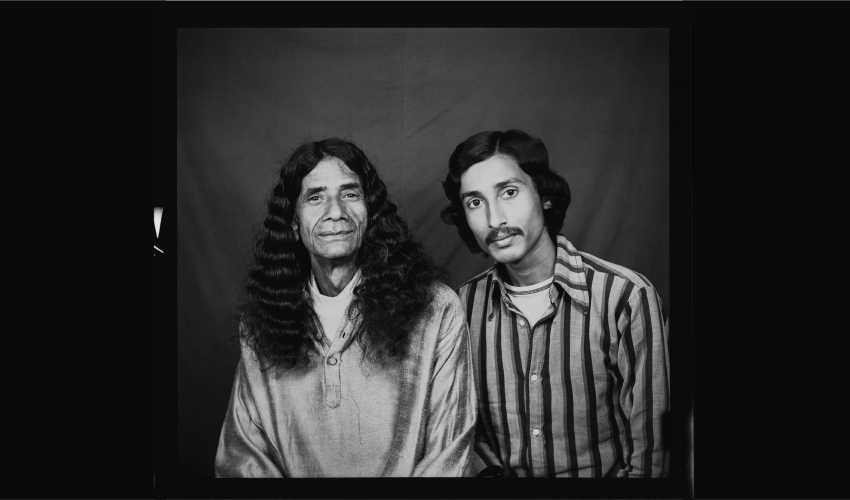

Nasir Ali Mamun, known as the “Poet with the Camera,” has been a groundbreaking force in Bangladeshi portrait photography since the 1970s. His iconic black-and-white portraits of figures like Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Mother Teresa, and Dr Muhammad Yunus capture the soul and history of a generation. Driven by a profound love for light, shadow, and subtlety, Mamun sees his camera as a pen that writes visual poetry. Now at 72, he envisions creating a “Photoseum” to showcase his collection and inspire young photographers to follow their own artistic instincts, much as he has throughout his career.

MWB sits down with the “Camerar Kobi” to discuss his artistic philosophy and dreams.

Poet Shamsur Rahman gave you the title “Camerar Kobi” or “The Poet with the Camera.” What inspired this title?

I once asked the same question to the poet, and he simply replied, “Why not?” Shamsur Rahman told me that while he writes poems with a pen, I craft them with my camera – that there’s something distinctly poetic in my style. This is why he called me camera kobi. He admired how I captured the play of light and shadow with subtlety and authenticity, seeing me as more than just a traditional portrait photographer. I believe this is why he chose to honor me with that title.

Your career has spanned several decades. How has your perspective on portrait photography evolved over the years?

The dream of photography sparked in me when I was an unhappy child. My only access to see, read, and “consume” photography was through newspapers. I became a regular reader of images, studying newsprint photographs of celebrities with great care and curiosity. It was an insecure journey when I first believed I could become an image-maker.

With no formal training or guidance in photography, I borrowed a camera in 1967 and took my first few photos, starting with my elder brother. That “first click” felt like pressing down on planet Earth itself! The mechanism and power of creativity through a camera utterly captivated me.

Since childhood, I have been a fan of great personalities. In 1971, I inaugurated portrait photography in Bangladesh, beginning to capture the influential minds of my generation. After the Liberation War, I noticed that most Bangladeshi photographers were nature-focused, with only a few venturing into portraits. Portraiture was largely unknown and undervalued. I wanted to chart a new frontier.

The 1970s were a time of global upheaval. Oil prices soared, food crises loomed, the Vietnam War neared its end, but conflicts continued across the planet, leaving people hungry. In July 1969, humans landed on the moon, and astronauts captured portraits of Earth from there. It was a thrilling moment for civilization, yet the world faced profound crises. Amid the challenges and pain of the 70s, I pioneered portrait photography in Bangladesh to document the rich history of our country’s most inspiring figures.

We all experience change at different points in our lives. These changes come in countless forms, similar to those you see in nature. In my portraits, you’ll find a consistent tone, akin to the sound of a behala [violin]. This tone is poignant, evoking memories of nostalgia. The lives of the people I have photographed – poets, writers, and musicians – carry the same resonance as a violin’s tone. Their lives are defined by the interplay of light and shadow. They never sought popularity, and as a result, they were often not widely recognized or celebrated by the general public – just as my work didn’t attract a large following.

At the start of my career, I had neither the money for a camera nor film. I lived in poverty, yet found contentment in the work I created. One-third of my life has passed in scarcity, much like the lives of the subjects in my portraits. These photos tell stories of insufficiency, neglect, and pain. It wasn’t a conscious decision; instinctively, I captured most of these photographs in black and white. Throughout different times, if you look closely, you’ll notice that my photos reflect the climate and natural beauty of Bangladesh. For example, my portraits of poet Shamsur Rahman embody the essence of Dhaka. I didn’t photograph him in a high-rise building, but rather in secluded spaces or on the banks of the Buriganga.

Yet, anyone looking at those photos can sense the bustling life of the capital through them. Likewise, my portraits of SM Sultan are imbued with the depth of shadows in black and white.

To me, the camera is like a paintbrush or a pen. The play of light and shadow in black and white is an art form, timeless against a world of color. I don’t merely press the shutter; rather, it’s the “hard drive” of my heart that captures the moments. Inspired by rare faces, I invite shadows into my portraits.

You’ve photographed many notable personalities in Bangladesh. Who was the most challenging subject to capture?

There isn’t a single person who comes to mind; instead, I’ve had different experiences with various personalities. During the 70s, photography mainly fell into three categories: photojournalism, studio photography, and freelance photography. Freelance or creative photographers generally focused on landscapes or cityscapes. However, no one was truly dedicated to portrait photography.

Just before the Liberation War, I began my journey in photography, a period that posed significant challenges. The personalities I captured in my portraits were exceptionally unique –figures like SM Sultan or Dr Muhammad Yunus. You won’t find another SM Sultan or another Dr Yunus. Each is distinct in their own way, and working with such individuals requires deep reflection on their life, work, and personality. It’s akin to extracting rare pearls from the ocean.

Even now, I sometimes struggle because capturing the essence of a person’s life isn’t easy; it takes great effort to truly understand and reflect who they are in a single image.

You’ve mentioned that true photography requires more than simply clicking a button. What do you feel is ‘missing’ in much of today’s digital photography?

I always say that photography is an art. Painters create with their brushes and colors, while writers express themselves with their pens. At their core, they are all creators, artists with passion in their hearts. Similarly, a photographer is an artist, crafting with a camera.

In our time, everything was manual – no digital conveniences. We worked with film and manual cameras, and producing a photograph was an incredibly time-consuming process. We had to take the film to a photo lab, develop it, and print it in a darkroom. Though the process is much easier now, one thing remains essential: a photographer must have a true understanding of their camera. The bond between a photographer and their camera is lifelong, and I believe this relationship is crucial.

Today, we are witnessing a revolution – the rise of nanotechnology. However, I was born with an analogue camera in hand, so I don’t consider myself part of this digital revolution.

A true artist respects nature and its rhythm. It takes immense patience, sacrifice, and dedication to truly master the art of photography. If you genuinely want to be a photographer, you must accept the sacrifices it demands. How many are truly willing to make these sacrifices? Very few, I would say.

Your photo album ‘Ananta Jibon Jodi’ features Humayun Ahmed. Could you tell us about the experience of capturing such an iconic figure?

Humayun Ahmed was a very busy person, so when he asked me to take his photos, I asked if he would be able to give me the time needed. However, he struggled to set aside enough time for the sessions, and soon after, he became unwell, which prevented me from continuing with the project. Despite this, I had a very good relationship with him. After his passing, his publisher approached me, asking if I could complete the project. Although I was initially sceptical due to the quality of the existing photos, I ultimately finished the album in memory of Humayun Ahmed, as he was truly a warm and beloved person.

If you could have one more opportunity to photograph any person you’ve ever worked with, who would it be?

There are indeed people who come to mind. One of them is Nelson Mandela. I tried to reach out to him while he was alive, but unfortunately, I couldn’t get in touch. Similarly, I’ve always wanted to work with Noam Chomsky, and I even attempted to contact him while I was in New York. However, as these are highly renowned personalities, there are many restrictions in place, making it diffcult to connect with them.

What gives you peace of mind these days?

At 72, I’ve decided to avoid ceremonies and functions as much as possible. Some people think this makes me appear arrogant, but that’s not the case. I simply prefer to write and savor my solitude. I’ve recently begun working on a biography, a project that may take years to complete.

I am also an avid collector, with a collection of stamps and coins from the British period. I dream of curating an institution, the “Photoseum,” where the younger generation can explore my portrait photographs alongside my collection of works featuring other writers and poets.

In a world full of fleeting images, what advice would you give photographers on creating work that has depth and stands the test of time?

I would say, don’t follow anyone’s advice blindly; instead, listen to your heart. In my time, we only had analogue cameras, but now the younger generation has access to new technology. My advice is to use these tools to create something unique, something with lasting value.