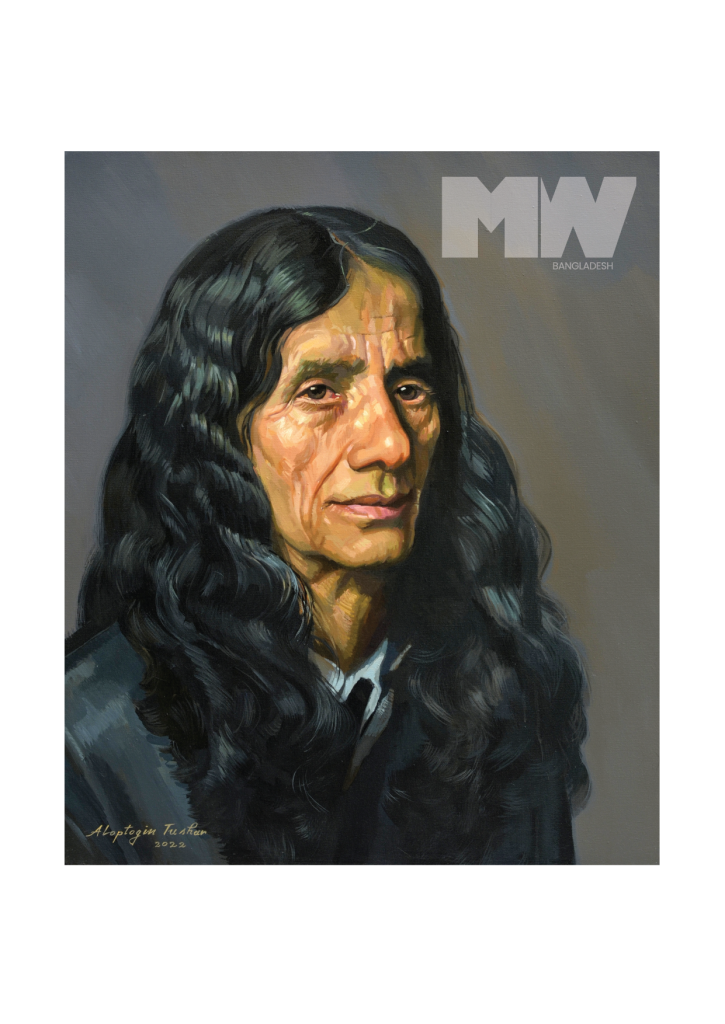

The story of Sheikh Mohammed Sultan, or SM Sultan to the wider world, reads like a fantastic folk fairytale. The son of a humble mason, whose remarkable talents are discovered by powerful patrons who send him to a foreign city, where he escapes the rigors of the classroom to explore the wider world, where he is feted and celebrated alongside masters, but at the height of all that glamor, he turns his back to the glitter and returns to the countryside where he lives as a recluse and champions for equity and the visibility through his stunning artwork.

Even after his death, his commitment to indigenous themes and unique style continues to inspire, celebrated through numerous exhibitions and collections. SM Sultan’s life and art were inseparable from the cultural fabric of Bangladesh. His legacy goes beyond art into the cultural and historical narrative he helped shape, earning the prestigious Ekushey Padak in 1982 and the Independence Day Award in 1993. On the occasion of his birth centennial, MW Bangladesh pays tribute to his extraordinary vision.

By Sabrina Fatma Ahmad

“If you’re trying to understand the life of Sultan, you must do so through the lens of his accidents,” says Nasir Ali Mamun, eminent photographer and long-time associate of the departed artist. We are speaking on the phone, and this is in response to a question about the plans for the centennial celebrations, so naturally this begs a request for clarification. “There are happy accidents, and there are some unfortunate ones, which mark his journey,” he continues. “Ultimately, SM Sultan was propelled by an internal philosophy that gave little regard to things that contemporary social conventions put a lot of value on; we can admire his way of thinking, but it would be hard to emulate him.” Mamun, who is a member secretary of the Sultan at Birth Centenary: National and International Celebration Committee, provides an example with the context of Sultan’s birth year. “He was born in a remote village, and largely had a nomadic life, so there are very few documents that can settle the argument. Various reports and papers have put down different dates, such as 1923 or 1922 or even 1925 as his year of birth, but Sultan himself affirms that he was born on August 10, 1924, so that is the one we go by, and according to that, this year, we celebrate his 100th.”

SCHOOL OF LIFE

And indeed, it seems like a series of unexpected events governed the trajectory of this incredible artist’s life. Born in a remote village in Narail, to a humble mason, Sultan may have ended up in obscurity like so many nameless children born around the same time in the same area. However, destiny had other plans for him. His father, Sheikh Mohammad Messer Ali, worked as a mason, and young Laal Miah, as he was fondly called, was his apprentice. Even as a child, Sultan felt a strong artistic urge, seizing every opportunity to draw with charcoal, and developed his talent depicting the buildings his father worked on.

When Sultan was 10 years old, Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee – the illustrious son of Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee, a renowned Bengali scholar and thinker – was visiting the Narail Victoria Collegiate School, and Sultan drew a pencil portrait of the visitor. The pencil sketch impressed Dr Mukherjee and others. This would be an early example of the child’s emerging talents being recognized by important patrons. His humble background would probably have cut him short by financial constraints, especially since he dropped out of school after only five years and didn’t complete his matriculation – but for this kind of attention. In 1938, Zamindar Dhirendra Nath Roy, an art aficionado, became the patron of Sultan’s works and brought him to his residence in Kolkata where he stayed for three years.

This restless push-pull of academia and the art world would characterize his whole life. In Adam Surat Tareque Masud’s short biopic on Sultan, celebrated filmmaker Alamgir Kabir narrates: “Having been raised in the freedom and wiles of the village, his temperament was not suited for the confines of academia.” Sultan arrived in Kolkata as a penniless youth, yet he was fortunate to find warm and nurturing support from important figures. Aspiring to join the prestigious Calcutta Art College, Sultan excelled in the entrance examination, securing the top position. However, his lack of a matriculation certificate initially disqualified him under the existing regulations. Thanks to the advocacy of Professor Shaheed Suhrawardy, who had seen his work, Sultan was granted special admission. While his brief foray into academia gave him some exposure to a variety of styles and techniques, his restless nature once again got in the way, and Sultan was unable to complete his degree. He left the college and embarked on a career of freelance painter of portraits and landscapes in Kolkata, expanding his travels and increasing his exposure to the figures and ideas that would inform his work.

After some success with his exhibitions in India, Sultan came to Dhaka, to find himself disqualified to be a teacher at Zainul Abedin’s Government Institute of Arts in 1948 because he had no academic certificates, to find himself to be perceived as “a painter who cannot even hold a brush” by some critics, according to Ahmed Sofa’s discourses. This may have impacted him in a way. After teaching art at Parsee School in Karachi, starting 1951, when he made his final return to his homeland in Narail, he chose to teach art to the village children.

In 1954, the then District Magistrate of Jessore, Ghyasuddin Ahmed Chaudhury, came to know about Sultan, recognised his greatness, helped in setting up an art school at Narail and offered him patronage. His son, Enam A Chaudhury, who became friends with the artist, also provided support, like setting up the Institute of Fine Arts and Shishu Swarga.

In Adam Surat, Sultan says: “I have a special interest in trying to help village children. My main concern is not to teach them; rather I like to encourage their own self-expression. I show them drawings. They have a tendency to draw according to certain rules and conventions. I try to help them bring out their own inner vision in their art. Then I see their innate talent bloom.”

INFINITE AURA

While it took some time for the establishment to acknowledge SM Sultan’s worth, he had never been without admirers who recognized his talent, in highly transformative ways.

When he realized that the Calcutta Art College wasn’t for him, the artist began to travel through India, soaking up the scenes, paying through his art. He visited Delhi, Agra, Shimla, Lahore, Kaghan Valley and Kashmir. At Shimla in 1945, a few local art enthusiasts organised a solo exhibition of Sultan’s paintings – his first ever, and it was quite the debut, Enam A Chaudhury tells us. The Maharaja of Kapurthala inaugurated the show, and later invited the young artist as his personal guest at Shimla and Jalandhar. At Shimla, Sultan also developed a friendship with the young Amir Habibullah. He spent long periods with him as his personal guest. Later on, he went to stay with Amir’s father-in-law, the Nawab of Amb. Those were the days when he kept on painting beautiful landscapes of Kaghan Valley and the arduous life of its hard-working people.

In 1950, Sultan toured New York, Washington, Chicago and Boston in USA where he held five exhibitions of his works. Later on, he held four exhibitions of the same in London, UK. Out of these, one was joint, in which Sultan’s paintings were exhibited along with works of Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Matisse, Vincent Van Gogh – some of the greatest in the world of art. This was his experimental landscapes era, which drew some comparisons to artists like Picasso and Van Gogh.

In an interview with Weekly Prahar on May 6, 1987, Sultan addressed these comparisons, in his gentle way:

“There are some differences between Picasso and me. Picasso shifted from figurative art to non-figurative art, and I shifted from non-figurative art to figurative art. Picasso painted a picture of the violence inflicted on Guernica. I painted a picture of sacrifice.”

In late 1975, Sultan graced the National Art Exhibition with his presence. His inaugural art exhibition in Dhaka and his second in Bangladesh, which was held in 1976.

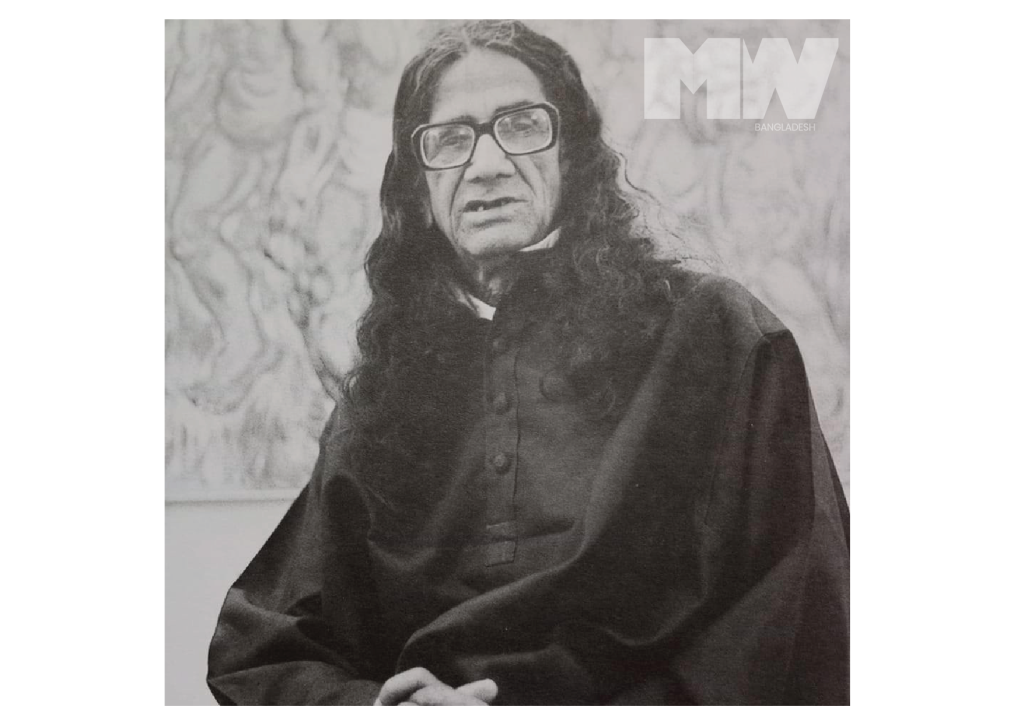

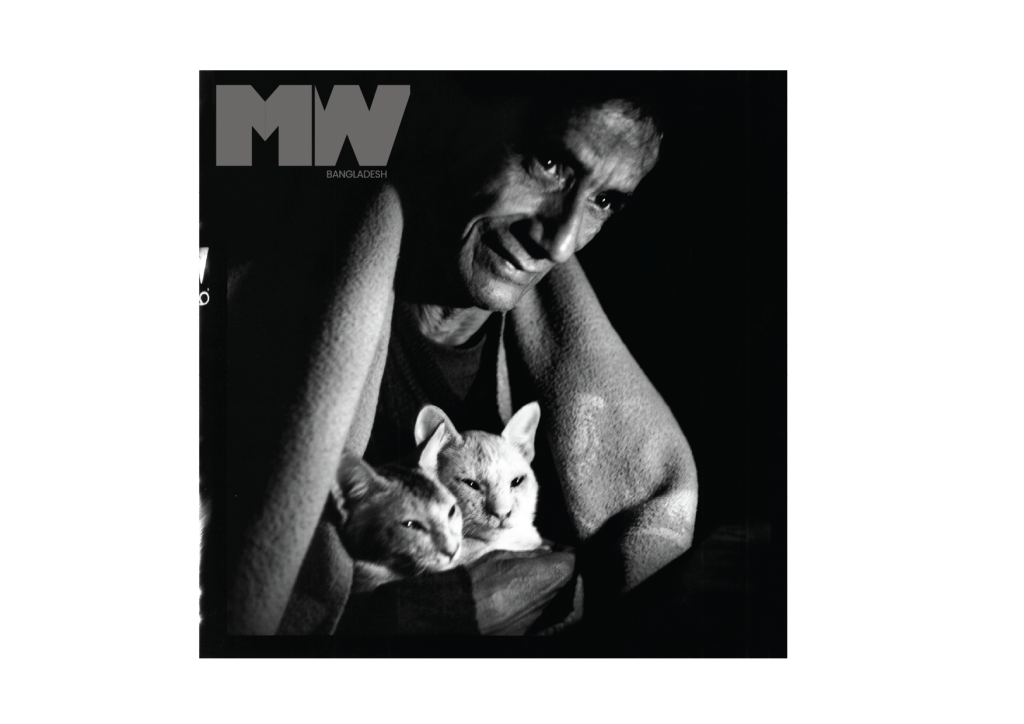

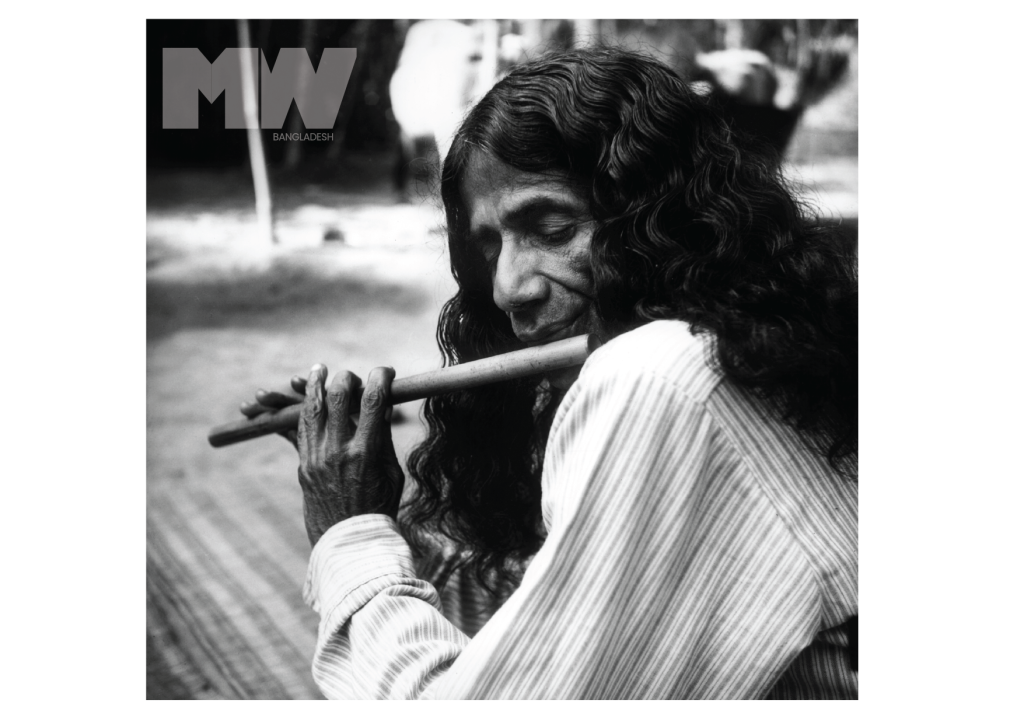

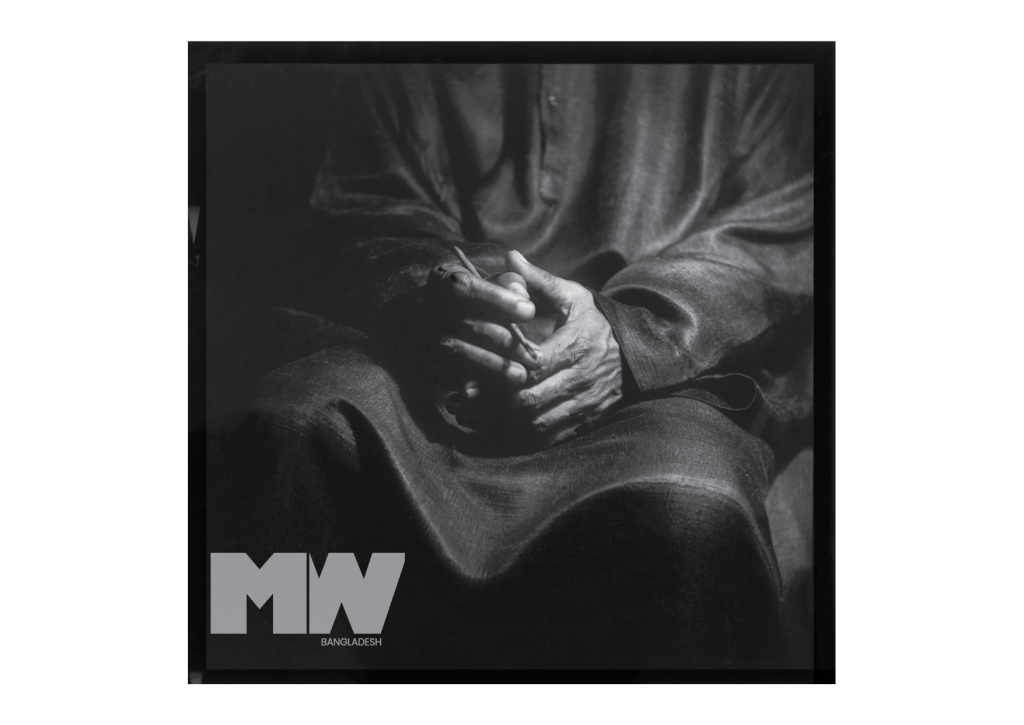

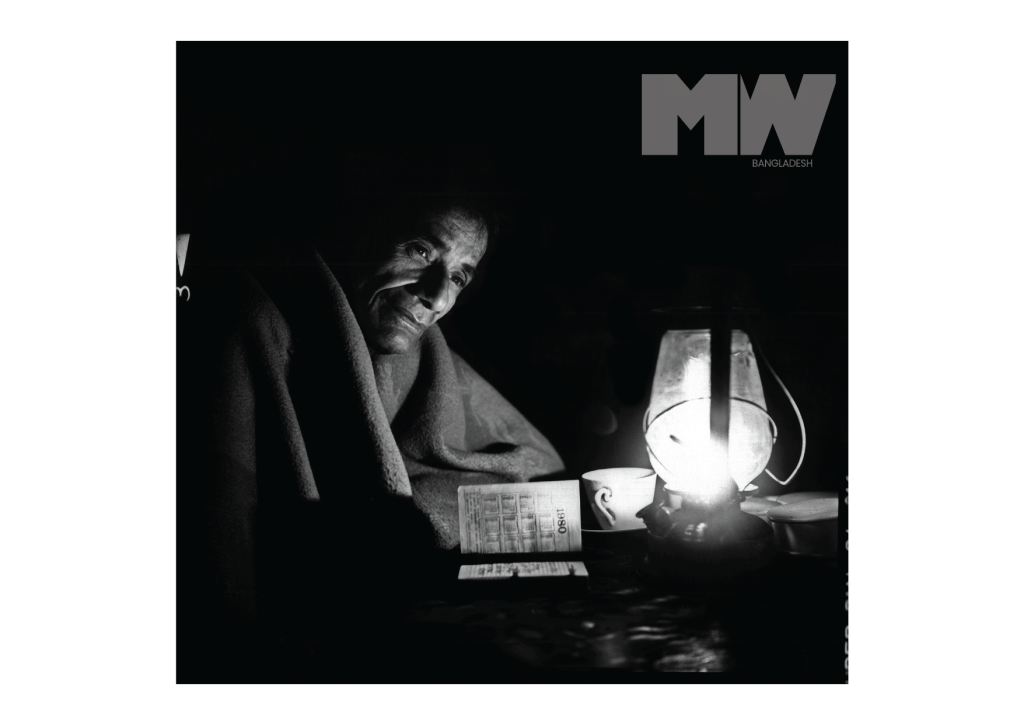

Over the phone, Nasir Ali Mamun is telling us about his own fateful first encounter with the artist. “I first met SM Sultan back in 1976, at the Shilpa-kala Academy. Actually, I had seen him the year before, but hadn’t plucked up the courage to approach him. He was already such an acclaimed artist, so I wasn’t sure how he would react to me. When I did seek him out, he was staying at the Academy, and I remember seeing him in his quarters there, sitting on the floor, eating a simple meal out of a tin plate, which he shared with several cats that surrounded him. Contrary to my expectations, he was soft-spoken and polite, addressing everyone he met as ‘apni’ and we got to chatting. I felt confident enough to ask him to continue our conversation in Ramna Park, where he let me take his photos.”

The friendship that formed there lasted throughout the years, and Nasir Ali Mamun would go on to extensively document the artist’s life, and be witness to the many ‘accidents’ that created all the various plot twists in the story of SM Sultan.

In 1984, the Bangladesh government conferred the Ekushey Padak on SM Sultan and Cambridge University declared him the Man of Asia.

He was honoured with Swadhinata Padak in 1993 and Charushilpi Sangsad Sammanana in 1986. The Bangladesh government accepted him as the resident artist.

Apart from being awarded prestigious awards, accolades, and being featured in top art institutions, Sultan received wide press coverage and laudatory critical reviews in renowned newspapers like The New York Times, Washington Post, The Telegraph, The Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, and many more.

OF ART AND OWNERSHIP

Perhaps the most interesting twist in the tale comes with his decision to return to Narail in the 50s, at what was then the height of his fame and acclaim. Eschewing all the glitz and the glamor, he retired to the banks of the Chitra, leading the life of a recluse, squatting in abandoned temples and ancient ruins, occasionally even sleeping under trees, according to Adam Surat. The local villagers grew accustomed to the odd sightings of Laal Miah in his signature black Panjabi and his long curly hair, and the sound of his flute at night.

From the 50s to the early 70s, he remained in self-exile, until his personal life took a curious turn. As he became accustomed to the locals, he met a destitute widow who had two daughters. “Sultan became involved in a relationship that can hardly be explained in usual norms,” says Alamgir Kabir, describing the artist as a “confirmed bachelor” who stayed away from any amorous entanglements. The deep affection and care the women bestowed on him brought him out of his exile and back into the world of art. For about a decade or so following the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, what now seems Sultan’s most fertile phase, a re-envisioning of the community has taken place through a utopian “communistic vision.” And this gave rise to myriad imageries of a vigorous peasant population set against the rural landscape – gigantic canvases dominated by muscular peasants in a revolutionary spirit that endures to this day.

The hardships of the villagers that he experienced had a profound impact on his life, and his art. The dreamy blue watercolor landscapes, the impressionistic renderings of fields and nature, began to give way to works where the farmers began to take center stage on the canvas.

In an interview with Weekly Prahar on May 6, 1987, Sultan highlighted the inspiration behind his depiction of farmers with muscular forms.

“Farmers are the true heroes of our land,” he explained. “Can a hero ever be frail? They are the very heart of our existence and thus must be portrayed as robust. They drive the plough into the harsh soil to yield our crops, yet they often endure hunger and poverty. The reality is our survival hinges upon their labor. Despite their real-life emaciation and deprivation, I choose to represent them as symbols of strength. I hope that this portray-al will reflect a vision of prosperity and respect for their vital role,” said the iconic artist.

In his peasants-as-the-hero landscapes, Sultan inserted the issue of “ownership,” about which Professor Burhanuddin Khan Jahangir dedicates a few lucidly written passages in his book titled Deshojo Adhunikota: Sultan-er Kaaj (lit. Indigenous Modernity: Sultan’s Work) to outline the “radical seeing” the pioneer modernist has given rise to.

This “radical seeing” of ownership was also applied to other aspects of his life. Nasir Ali Mamun, who visited Sultan in the abandoned zamindar house he was living in during the later part of his life, talks about the overgrowth, the snakes, and other creatures that had to be gently routed out before the place became inhabitable, the dimly lit corridors where he set up his “studio,” were surprising to the photographer, but what frustrates him, and other scholars of the artist, is how little regard Sultan placed upon his own things, including his art. Forgoing the expensive art materials he surely had access to, especially after his resurgence in the 70s, Sultan devised his own canvases out of jute, which he treated with gab fruit resin used by fishermen, and mixed his own paints made from locally made materials, to make art and art supplies accessible to the impoverished masses he lived with. He also showed little regard for his pieces once they were finished, abandoning some, leaving others to rot. Adam Surat documents large pieces that ended up functioning as ceilings or wall partitions in some hut, while others made their way to grand displays in exhibition walls, private collections and the living rooms of the wealthy. The artist didn’t seem particularly concerned about any over the other.

A lot of his earnings from his re-emergence into the literary scene, went into his dream of promoting the artistic talents in his village. He first established the Nandan Kanon Institute of Fine Arts in Narail in 1953. In 1978, SM Sultan established Shishu Swarga at Kurigram on the outskirts of Narail town to teach painting to children. He also commissioned an engine-driven boat, financed by funds raised by Ahmed Sofa, for the students so that they could learn boat riding and enjoy the serenity of nature. But by the 80s his health was in decline, and he was unable to further many of his plans.

Sultan died in Jashore Combined Military Hospital on October 10, 1994. He was buried at the yard of his own house in Masimdia-Kurigram area of Narail town. The artist left behind a rich legacy of celebrated works such as “First Plantation” (1975), “Char Dakhal” (1976), “Harvesting” (1986), and “Fishing-3” (1991), alongside countless other master-pieces, which have lost been lost due to the passage of time.

Before our phone conversation is cut short by a call to prayer, Nasir Ali Mamun is talking about the July Uprising, the spirit of students and the working masses teaming up to protest against inequalities, and the role of visual art in the revolution. “To think that these young minds, who would choose art to carry their message, that the walls and streets, not just in Dhaka, but around the country, would be colored by the protests, is the culmination of the things that SM Sultan stood for. I truly believe that he was with them in spirit during those weeks. They may never have met him, but anyone who views those giant canvases can feel the raw power coming from it, imbued with a sense of justice.”

An artist who renounced imposed ideas to create revolutionary art, using sustainable, indigenous materials, who lived and died by his personal philosophy? 100 years after his birth, he’s never been more relevant.

Photography by Nasir Ali Mamun/ Photoseum©

In Association With HSBC