By Hammad Ali

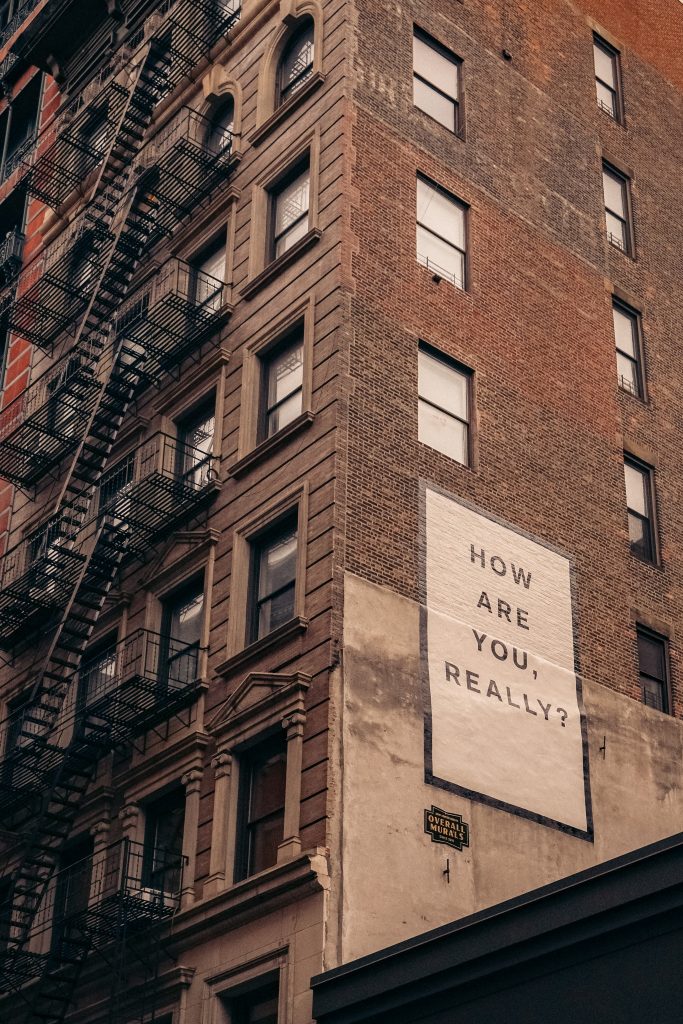

We need to change how we talk about mental health

A lot has been said about the stigma associated with someone coping with mental health issues, or openly seeking out treatment for it by visiting mental health professionals. Full disclosure, I myself have been guilty in the past of trivializing mental health concerns, albeit not in the same way. Today, as someone who personally has been struggling with nearly a decade of depression, but also constantly working on learning more, I see the flaws in my thought patterns in my younger days. I thought I would write a little today about some of the unhelpful beliefs many of us harbour about those of our loved ones who are fighting mental health challenges.

My family has a history of Type 2 Diabetes. Type 2 Diabetes is when your pancreas does not make enough insulin anymore. Insulin being the hormone needed to metabolize all the glucose we consume; this means that the glucose runs amok in the bloodstream instead of being properly processed for energy. Over months and years of this, this causes vein and nerve damage, as well as failure of major organs. Type 2 Diabetes can be caused by lifestyle, but the bottom line is, once someone’s pancreas has started failing to provide enough insulin, they now have a valid medical condition.

I now bring your attention to how we often tell someone with depression, for instance, that it is “all in their head”. Indeed, we are right. There is enough reason to believe that depression, panic attacks, generalized anxiety disorder etc. are often the result of brain chemistry, of the brain not regulating hormones adequately.

Which, to me, is the whole point. I mentioned Type 2 diabetes above, because when someone informs us that they are diabetic, we know what actions to take to make them feel cared for. If we are inviting them to a meal, we are mindful of the food options available. If they are somehow depending on us for their daily schedule, we take care that they have meals on time and have the opportunity to medicate themselves as needed. The one thing we do not do, at least I hope we don’t, is tell them “Oh it’ll be ok! Diabetes is just all in your pancreas!”

Because, you see, that would be theoretically correct and practically useless. Diabetes is in fact all in your pancreas, in the exact same way depression is all in your brain. They are both consequences of inadequate hormone regulation, manifesting in physical symptoms and hindrances to a regular lifestyle. In fact, the two share a few more parallels. Just like Diabetes is usually a lifelong condition, but can be kept from affecting one’s day to day to life inordinately through proper medication and lifestyle changes, depression is also usually long-term but can be managed. Point being, they are both medical conditions, have a lot in common, and while care must be taken to manage them, neither is a reason to feel ashamed of oneself. And neither can be managed by “cheering up” and “looking at the bright side”.

I am glad to say that at no point in my life did I think that cheering up, smiling more, and watching Adam Sandler, is the cure for depression.

I am glad to say that at no point in my life did I think that cheering up, smiling more, and watching Adam Sandler, is the cure for depression. And yet, I have been guilty of unhelpful thoughts about my own mental health challenges. For a large part of my youth, I struggled with depression, and felt that my loved ones are to blame. If only they cared about me a little more, I would not be feeling this way. Alternatively, if they truly even care about me at all, why are they okay with me feeling this way?

Some ten years later, I sought out professional help for my depression. Today, nearly sixteen years later, I have fresh perspective on the way I used to feel back then. Even at that age, when I had the flu, I went to the doctor. I did not ask my best friend, whom I have known for almost thirty years now, to fix it for me. I did not ask my siblings or cousins to put my leg in a cast that time I fractured my ankle. Nor have I ever asked my mother, blessed be her memory, to fix my eyesight because I am tired of wearing glasses.

The point I am trying to make is, even as a child I acknowledged that all those other things are healthcare issues. And when encumbered by these issues, I went to a healthcare professional, not ask my best friend to do something. Yet, I treated my mental health with a cavalier attitude that, over a span of years, only made it worse. More importantly, it costed me friendships with people I wore out with the constant demand that they help me fix it.

Today, I still struggle with mental health, but I am seeking professional help for it. I am mindful of my triggers, and manage my lifestyle to make it as less intrusive as possible. Best of all, I do not unduly burden my loved ones with my issues. Sure, I love them and I know they are there for me. But the crux of what I am trying to say today is, mental health is a healthcare issue. We need to treat it as such, even when it is happening to us. Especially when it is happening to us.

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema