Abak Hussain

First things first: Not having been invited to the premiere at Cannes, and with general release specifics still up in the air, I have not yet seen Francis Ford Coppola’s long-gestating epic Megalopolis. With a pained sense of FOMO, therefore I admit that despite being a 20+ year love-hate fanboy of the director, I am not yet qualified to dive into a discussion or review of one of the most significant slow-burn cinematic happenings of modern times. The only other equivalent events I can think of are Terence Malick’s existentialist comeback The Thin Red Line (1998) and Stanley Kubrick’s return the following year with the highly divisive Eyes Wide Shut (1999). And now we have Megalopolis – a star-studded, big budget film with a premise both epic and intimate, by one of the most important film-makers of our time, but one who, like a child at play – or like most creative geniuses, if you will – is as good as building up his own legacy as he is at tearing it down.

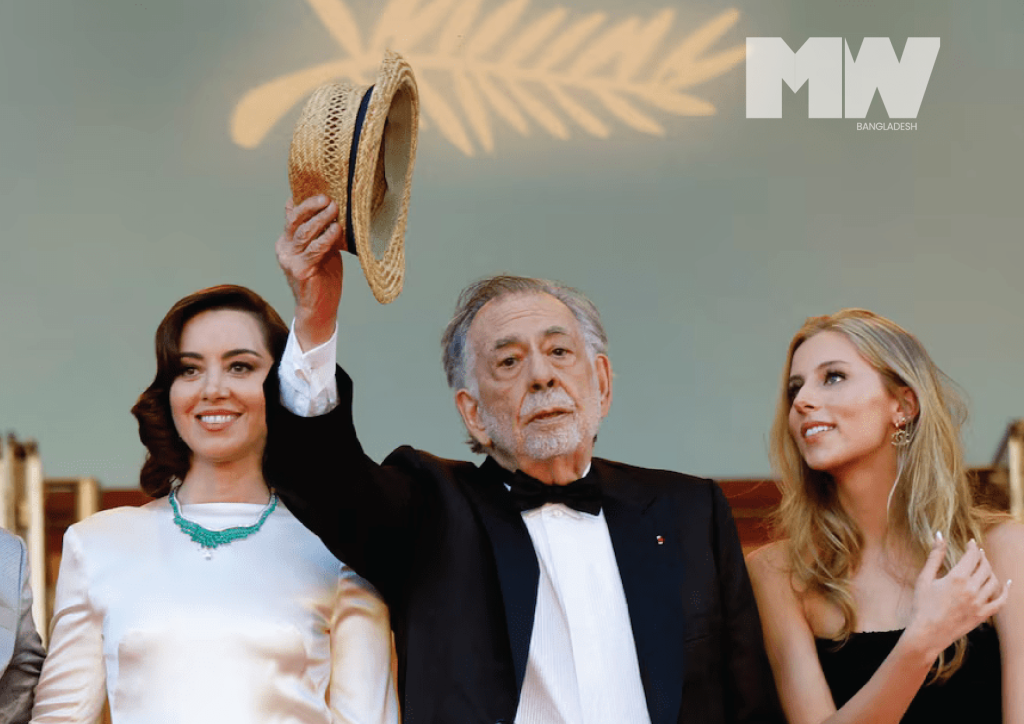

Early reports of the reception are a mixed bag – as expected, they are contradictory and a bit confusing. There was a 10-minute standing ovation. No no, it was booed. But no, some people were simply silent, trying to process what they had just witnessed. And the standing ovation? Let’s face it, when the 85-year-old Francis Ford Coppola is in the same room as you, it does not matter what he has just screened, and it does not matter if the picture makes sense or not, you stand and applaud, and if you can get near him, you prostrate yourself at his feet and you say: Thank you for all you have done, especially back in the Seventies. Thank you for tearing up the movie-making playbook created by a conservative and capitalistic studio system and bringing the art form back to the hands of the artists. Thank you for kicking down the doors to usher in New Hollywood, making way for the Martin Scorseses and the Steven Spielbergs and the William Friedkins and the George Lucases, all those radical visionaries who would not have been able to fly under the claustrophobic studio system that was once ruled by the likes of John Ford and William Wyler. New Hollywood, starting in the late-Sixties and collapsing sometime in the early-Eighties, was the hottest party in the American film business, and keeping a watchful eye over it all, egging on the youngsters like a mentor, or shall we say, ahem, like a Godfather, was Coppola.

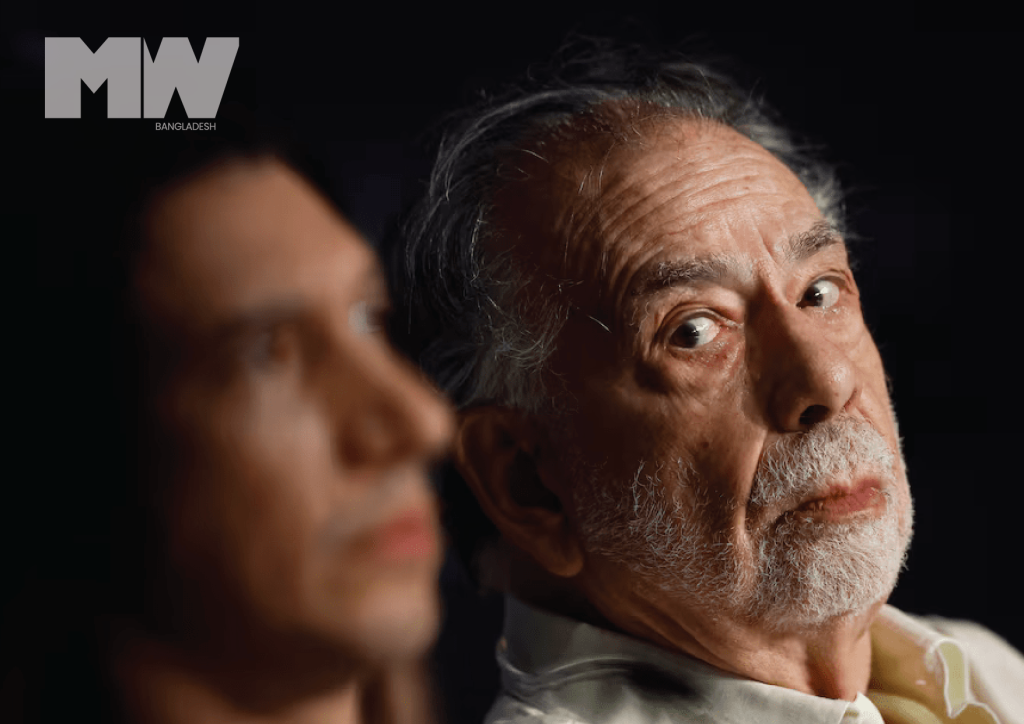

Charting Coppola’s involuntary legacy is a fool’s errand, and I have no wish to embark upon it. But how to describe the soul of the artist himself, one who has been to hell and back, one who has been praised and damned with equal vigor? A crew member from the set of his latest film, according to a story in The Guardian, said: “This sounds crazy to say, but there were times when we were all standing around going: ‘Has this guy ever made a movie before?’” How does one explain such a statement, a sentiment echoed by much of the cast and crew who were frustrated to death by Coppola’s approach, slogging his way through a troubled production that bewildered critics on opening night, one critic saying it was as if someone had snuck into the editing room and randomly stolen footage from the rough-cut, so random does the film seem at times? How does one explain this sort of on-set behavior and this sort of result from a man whose trophy cabinet contains five Oscars, two Palme d’Ors, and six Golden Globes?

The answer, I personally believe, lies in Coppola’s highly personal view of art. Coppola has always viewed cinematic art, I think, as the commitment to throw caution to the wind and push the medium forward. This is how he did it in the Seventies, and while he has gotten old and the world around him has changed, his creative soul is still very much New Hollywood. After Scorsese made those controversial “not cinema” comments regarding Marvel and superheroes, Coppola was the first to run to his boy Marty’s defense, because if anyone harbors contempt for money-grubbing studio executives, it’s Coppola. Arguably, the late-capitalist studio system of today is much worse than the era of Classical Hollywood. The environment might have been stifling in the Fifties, but there was still a balance between art and commerce. But now in the multiplexes, the game is called make money or go home. This is why when you go to the theater, you are surrounded by franchises and sequels, all buried under an avalanche of brain-numbing CGI which infantilizes the audience right after taking their money. Where is the authorial vision? Where is the reckless creativity that spills a director’s innermost anxieties onto the screen: Taxi Driver, The Exorcist, Apocalypse Now, Jaws? Simply put, giving a blank check to a brash, young genius is too expensive and too risky. Movies are screen-tested multiple times and audience reactions are gauged. The rough cuts are scrubbed and edited to an inch of their lives. Committees comprising of executives in suits sit around talking about demographics, and the science of how far a movie will climb in the box office, and if anything needs to be added or subtracted to avoid offending group X, or to curry favor with group Y. The result is usually an inoffensive, easily digestible movie, watchable in the afternoon, forgettable by morning, full of sound and fury and lazy special effects, signifying nothing.

In an interview with The Guardian’s Steven Rose about 14 years ago, Coppola had said: “I don’t think things through; I feel them through. And I know that half the time I might not land right, and maybe there’s a pleasure in that, but in my life I have to say, that’s served me well. When you’re this old guy dying, you don’t wanna say: ‘I wish I had done that and that.’ In my case, I did it. I did all the things other people would just regret that they didn’t try. Because, in the end, you die. You don’t get any award for just being conservative.” Back then, Megalopolis was already on his mind. Will the initial bad reviews hurt him, or is he, as this quote suggests, beyond giving a damn? One thing is clear though: from what we have seen regarding the reception to the works of Malick, Kubrick and a few others – when you make your own passion project exactly your own way, far, far away from the commercial status quo, the immediate reactions may be hurtful. Only in time, maybe a couple of decades, will we know if it was all worth it.

Abak Hussain is Contributing Editor at MW Bangladesh.

-

mw

-

mw

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain

-

Abak Hussain