MWB Desk

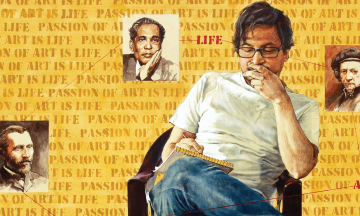

Recently, the play Begum’s Blunder – an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s famous work Lady Windemere’s Fan – opened to rave reviews in Dhaka. MWB had a quick chat with the play’s producer, the multi-talented Sadaf Saaz about why this play works so well in the present day, Dhaka Lit Fest, and how she manages to keep so many irons in the fire.

I want to start with your latest project, the play Begum’s Blunder which is a re-telling of an Oscar Wilde play from over 130 years ago. Could you please tell us a bit about the origins and motivations behind this idea? Why this particular work, and what makes it so relevant to our country in the present day?

Oscar Wilde’s classic is really a timeless story which brings out the hypocrisy of our society, as well as the double standards that women face, along with being fun and entertaining at the same time. The play has strong women characters who face their own restrictions and dilemmas in an unforgiving society – somehow this idea of being a “good woman” and “bad woman” is still very much part of the part and parcel of what women have to face even today when they think or behave independently or out of the norm.

We loved the idea that we could bring a story originally meant for aristocratic 19th century London, and set it in 1920s British Raj in Bengal, and still make it relevant for today’s Dhaka. Naila Azad did a brilliant job of adapting and directing this work for our context, as well as keeping the crisp witty dialogue of the original but making it very much our own through the costumes, the language and the references. We had sort of “piloted” this in a much smaller version in our small pocket theatre space a few years ago, and it had really connected to Dhaka audiences. Expanding the production to an 18-member cast, with elements of intersecting performative art forms, enabled us to really explore not only the drama unfolding, but also connect to audiences on various levels.

Bringing together a group of actors from diverse backgrounds, generations, and experiences was a challenge and a delight too. The play was therefore important to us in various ways – to experiment with various art forms to tell stories, to use different creative spaces, to put on a show that would connect across generations and backgrounds; to be able to tell a story that would make people think but also just be great to watch for pure entertainment – and to prove to ourselves that live theatre is still very much a powerful medium to tell these stories.

You do so much work, frequently with several irons in the fire. One of the many roles you wear is activist. How do you view your creative pursuits in relation to your cultural/social activism – are they related?

Being an activist in the cultural sphere for me is more about working to ensure that different cultural and creative forms can be showcased, bringing out different perspectives and encouraging and supporting excellent creative work to happen. The idea is to work towards enabling artists and performers to have the platform and freedom to express themselves, and doing whatever is needed support and nurture literature and the creative arts in the cultural space. In “growing” economies, often the creative arts are not given as much importance without there being any direct economic benefit – and hence we find a lack of patrons and support without being able to “show” any direct “return on investment” in these areas. Performances like Begum’s Blunder begin to show sponsors and promoters that there is an engaged and vibrant audience for this kind of content; that it could have great returns too eventually. To work to create an atmosphere where one strives for excellence and doesn’t settle for mediocrity is key for me.

As for bringing through activist messages through certain work – yes we do projects we believe in, but the idea is to show the different layers of the human condition and tell stories which mean something, without being prescriptive or encourage cultural “propaganda.” Being part of a hegemony which only encourages certain types of thoughts, or encourages cancel culture without a deeper thinking of issues, is something which one needs to be aware of; which is the anti-thesis of what we are trying to do.

Dhaka Lit Fest has to be the most daunting undertaking of yours. What is it like handling an event that big and complex? How do you see the future of lit fests in Bangladesh?

Dhaka Lit Fest has really been an incredible journey – from holding a small intimate festival in 2011 to our mammoth 10th event last year – where we had over 375 events over four days. As a live literary event there are continual challenges – but I think our strength has been staying true to our vision of continually striving to keep both the substantive curatorial part to a high standard, alongside the logistical side to be working like clockwork – and not forgetting the empathy and human connection to our audiences as well as our authors and artists.

Handling both the logistic as well as the curation site together is important – as both are needed to be done well for a good experience. One of the biggest challenges has been how to make this sustainable – especially given that the previous model has been to have these events for free. We introduced a small fee last time to Dhaka Lit Fest, to make this more of a festival for the people rather than fully sponsor led. In festivals abroad each session is usually charged for – so we do think that good art and culture should be supported by tickets, not just by a few big sponsors who may not always be willing to spend, or may change priorities.

Literary festivals though still prove that there is something precious and unique about coming together as communities, talking and having an adda – and dipping into topics and cross-cutting conversations – which ironically may be less accessible through our algorithm generated social media narrow silos. The great feedback and success of our last festival I think showed how people do want to get together in real-time and debate, discuss and experience literary, stories and cultural performances.

Your journey has been a fascinating one, and not at all predictable. You were born in the US, but you grew up in the UK, and yet you live and work in Bangladesh. You studied molecular biology but are known for your work in poetry, the arts, enterprise, activism. Do you see a particular lane as your calling? Is it all of the above?

I think it is all of the above! I feel that even all these seemingly different parts of me connect in a way that makes sense more than ever now. I do have several areas I want to focus more in going forward though – and platforms like festivals, productions and events that I put on through Jatrik help open people’s eyes to how other people think – and this intersectional way of looking at the world, will be more important going forward.

Could you tell us a bit about any projects you have in pipeline? Any thoughts or desires to dip into other areas? I read somewhere that you were working a novel? What’s next for Sadaf Saaz?

I hope to do much more in the creative space – by experimenting with events and productions, continuing works like Begum’s Blunder. I am writing a novel which I hope to finish one of these days. I also want to focus on my new bio and healthtech company EskeGen! A part of that would also be getting young people more interested in science and the amazing possibilities ahead – and hope to use the different platforms and mediums to do this too.