Rani Hamid is a powerful soul who has mastered the battle of minds, rising as a true queen in the game of kings. From the start of her chess journey, she has dominated with sharp intellect and strategic brilliance. Her mental resilience and tactical genius have made her a formidable force on the chessboard, securing victories in countless tournaments. As the reigning queen of chess in Bangladesh, Rani Hamid has shattered barriers, proving that in the battle of minds, there is only one true victor, one who can outthink, outlast, and outmaneuver their opponent.

By Neha Shamim

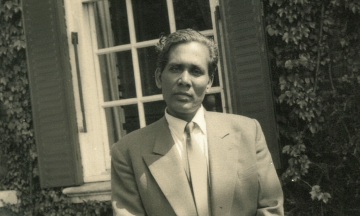

Rani Hamid’s introduction to chess was a turning point in her life. Born in 1944 in Sylhet, Bangladesh, her early interests were in outdoor sports like badminton and Athletics. However, it was after her marriage and move to Dhaka that her husband introduced her to chess, a game that would become her lifelong passion. Despite starting later in life than many competitors, and without any formal coaching, Rani Hamid quickly developed an extraordinary skill for the game, showcasing an innate ability for strategy and a mastery of patience.

Her chess journey began in the 1970s, a time when competitive chess was largely male-dominated, especially in South Asia. Rani defied expectations, balancing family life while focusing on mastering the complexities of the game. Her first breakthrough came when she entered a local competition, and from there, she rose rapidly through the ranks, earning widespread recognition for her intellect and tactical brilliance.

In 1985, she earned the prestigious title of Woman International Master (WIM), becoming a trailblazer for women in chess in Bangladesh. Over her career, she has won the Bangladesh Women’s Chess Championship over 20 times and represented her country in numerous International chess tournaments including the Chess Olympiads, cementing her legacy as one of the greatest chess players from South Asia.

This month, MW visited her at her residence to catch up on the story of her remarkable journey.

How did your early life and upbringing in Sylhet influence your journey into chess?

My father was very fond of chess and played it often. When I was young, I participated in many different sports, but at that time, kids typically didn’t play chess. It wasn’t considered normal for children to engage in the game back then. Whenever my father played, I was fascinated by it, but we weren’t allowed to touch the chessboard. Instead, we played outdoor sports like hadudu, basketball, running and numerous other local outdoor sports. Although I played many sports over the years, chess wasn’t one of them. My father taught me which piece made which move, but we weren’t allowed to play, as it was considered a game for adults.

Your husband Colonel Hamid introduced you to the game. What got you hooked?

After the Liberation War, the Bangladesh Chess Federation became a member of the International Chess Federation in 1979. In 1976, there was an advertisement in the newspaper about the first chess competition for women in Bangladesh. My husband came home and told me about it, knowing my interest in chess. I kept wondering if I should participate or not, after all, I didn’t even leave the house much, and I had four kids to take care of.

At that time, Dr Akmal Hossain, the national chess champion, was my neighbor, and I used to play chess with him occasionally. This gave me the confidence to participate in the women’s chess tournament in 1977. Dr Hossain supported me greatly in my journey. As a housewife who rarely left the house, he not only encouraged me but also took me to the tournament and stayed with me while I played. To my surprise, I became the champion in my first tournament, and that was the beginning of my chess career.

Even now, I continue to play, as I don’t have much work and I enjoy it. Bangladesh Biman has supported me a lot, providing tickets for my annual trips to London for tournaments. Thanks to their help, I was able to keep going.

Were there any other South Asian women who were known in the chess circle back then?

There were few female chess players from India who were very renowned at that time. I used to have a good rivalry with them and played intense matches. They used to come with their personal coaches which I never had but still I managed to beat them.

Tell us about your book Mojar Khela Daba?

After few years being a chess player, my husband suggested I write a book, which I later published under the title Mojar Khela Daba. I noticed that when women from rural areas came to participate in tournaments, they knew how to move the chess pieces but didn’t know how to write or understand the rules of the game.

Six months after publishing my book, I saw participants had learned not only how to write, but also the rules and other basic technical openings of chess from my book. I update it from time to time, as rules change or new ones are added. After that, no one said they didn’t know how to write. I also organized chess tournaments for women during that period.

To get so good at any field requires time and dedication. How did you manage this time?

By the time I started playing chess, my kids were all grown up, and I didn’t need to attend to them as much. I always had domestic helpers at home so could manage time for chess. I truly enjoy playing chess. So guess, when you have love and have passion for something you can always make time for it. In fact, I encouraged everyone in my family to take up chess, my sister, my sister’s children, and even my grand-daughter Samaha, who is very talented at the game.

How did it feel to win your first national chess title in 1979, and how did that moment impact your career?

It was a very special and joyful moment for me. The next day, news of the championship, along with my picture, was published in newspapers across the country. It was a truly satisfying experience. Having already won three times before, I had developed a taste for victory. The widespread publicity I received encouraged me to take the game more seriously.

Tell us about participating in your first International tournament.

The first Asian Women’s Championship was held in Hyderabad, India, in 1981, where participants from various Asian countries competed. Surprisingly, no one knew me or expected me to win. However, when I started winning the first five or six rounds consecutively, everyone was shocked—how could a newcomer win so many matches in a row?

At that time, the famous Khadilkar sisters from India—Vasanti, Jayshree, and Rohini—who had already participated in and won international women’s championships, were also competing. The Khadilkar sisters’ coach was visibly concerned. He approached me and asked several technical chess-related questions, but I didn’t know the answers, even though I kept winning. Later, I realized he was gathering information to help prepare his player, Rohini, for our match.

During my match with Rohini, my husband noticed that her sisters and their coach were in another room, planning and analyzing my previous moves. The match was very intense. Rohini kept going to the back room for advice and returned with the right moves, eventually leading to her victory. I finished third in that competition. At that time, supervision wasn’t as strict, and the Indian players took full advantage of that.

You’ve won the Bangladesh Women’s Chess Championship over 20 times. What was your mindset going into each competition?

I don’t overthink before my matches. I practice normally at home—I eat, sleep, and play. I enjoy the game, which keeps me going. However, I tend to make small blunders that have cost me matches. In the 5th Chess Olympiad, I lost a match despite having plenty of time, rushing a move in just 10 seconds while my opponent only had two minutes left.

Sometimes, opponents take 10-15 minutes to respond, and the wait makes me tired or impatient. I should be more patient, but I often rush and make mistakes. For example, I lost a match against the American champion due to a rushed move, even though they had only two pieces left. It’s a bad habit that sometimes costs me dearly.

How do you handle it when you lose a match?

Losing really bothers me. I often ask myself, ‘How did I lose? Where did I go wrong?’ I keep analyzing the game until I fully understand what happened. Winning doesn’t affect me as much as losing does. I don’t mind losing to an opponent who plays well; what disheartens me is losing because of my own silly mistakes. That’s when I feel truly frustrated.

How has the chess landscape in Bangladesh changed since you started playing, especially for women?

It has changed dramatically. Now, Bangladesh Police, Navy, and Ansar support players by recruiting them, providing a monthly salary along with rations, and covering expenses for international tournaments. So yes, the chess scene has changed remarkably compared to when I started.

When you participated in the Chess Olympiad in 2024, who were your toughest opponents throughout the time?

Every player is skilled. When I won against Argentina in the Olympiad, people were really excited. Since Argentina is well-known for football and quite popular in our country, everyone found it amusing that we beat them, especially since our football team could never compete with Argentina.

What is one life lesson you learned from chess that you apply to your daily life outside of the game?

There are many lessons to learn from chess. We must make the right moves at the right time; otherwise, it will impact our game. Similarly, in life, we need to make the right decisions at key moments. If we fail to do so, we may find ourselves stuck. To defeat the king, you must think carefully before each move, just as in life.

At 81, you’re still active in the chess community. What keeps you going, and what are your future goals?

I guess my love and passion for the game have kept me going. Sports are in my genes. My whole family is involved in sports. All three of my sons are well known for their athletic prowess, having represented the country in various sports. My eldest son, Kaiser Hamid, is a legendary football player. He played for the famous Mohammedan Sporting Club for over 10-12 years and was the captain of the Bangladesh national football team. My second son, Sohel Hamid, is a former national squash champion and also represented the country in handball. He was also a skilled cricketer and served as the ex-General Secretary of the Bangladesh Squash Federation. My youngest son, Boby Hamid, is a renowned former national handball player. My husband, Lt. Col. M. A. Hamid, was a distinguished swimmer and football player in the Pakistan Army. He was the founding president of the Handball Federation and received the National Sports Award in 1987 I suppose all these factors have helped me stay involved in sports for so long.

Now, I live in the future, having done everything I can for my country. I have published a book and supported local players in improving their game. Whenever I meet young players, I encourage them to play better by giving them tips. I also encourage their guardians to support their participation in sports. Time will tell.

You have met Susan Polgar, the strongest female chess player in history. How did it feel meeting her in the Olympics and what did you guys talk about?

Susan and I started playing together when she was 14 and I was 33. In 1981, in London, she looked older than her age. Her mother often vented about how men dominated the chess scene. Even after qualifying, officials wouldn’t let Susan play on the men’s team simply because she was a woman. The Polgar sisters—Susan, Sofia, and Judit—were trained by their father in various activities, including swimming and chess. He was very proud when the youngest sister, Judit, played on the men’s team, sitting at the first board while male players sat behind her. He worked very hard to help his daughters become top players in the world.

Susan, the oldest daughter, really likes me. She posted about me on Facebook with the caption: ’80 years young, Rani Hamid.’ She was happy about my win, and her post went viral, receiving a lot of appreciation from people.

How was your experience playing against some of the best chess players in the world and winning to highly skilled opponents?

I have many sweet memories from playing against top players on the international stage. In the latest Chess Olympiad 2024, I played eight games and won seven of them. I was shocked, as I thought the level of competition among women would be higher, and that at my age, I wouldn’t be able to win so many games. The other players were also surprised that I won so many matches.

There are a few other matches against top international players that I recall with great pleasure. In 1981, in Dhaka, I defeated the then national champion of Pakistan, Shahzad Mirza, in just 28 moves. The crowd was both surprised and thrilled, giving me a big round of applause. This game is featured in my book Mojar Khela Daba.

I have also beaten world junior champion Springer Leshay of Barbados and drawn games with notable players such as Hikaru Nakamura, the world’s No. 2 chess player, and Grandmaster Nana Alexandria during the Chess Olympiad. They were top players at the time.

Another notable moment was in 1983 at the Loyd Masters Chess Tournament in London, when I won against a Spanish woman Grandmaster. After the match, everyone came to congratulate me, and I was initially confused. It was only later that I learned that by defeating her I had earned my very first International Master norm. I hadn’t realized that winning this match could grant me a norm. Today, all players are well aware of these milestones.

A REMARKABLE JOURNEY

Rani Hamid’s remarkable journey in the world of chess is not just a testament to her individual talent and perseverance; it symbolizes the broader evolution of women’s participation in a game once dominated by men. As she continues to break barriers and redefine the chess landscape in Bangladesh, her story resonates with aspiring female players everywhere. Through her tireless advocacy for women’s chess, Rani has become a beacon of hope and inspiration, demonstrating that with dedication and resilience, any obstacle can be overcome. Her achievements, including multiple national championships and the prestigious title of Woman International Master, are not merely accolades but milestones that pave the way for future generations. Rani’s efforts in founding the Women’s Chess Organization and publishing educational resources reflect her commitment to nurturing the next wave of female chess talent. By empowering women to take up the game and providing them with the necessary support and resources, she is ensuring that chess remains an accessible and inclusive sport.

Moreover, Rani’s ability to maintain a balance between her family life and her passion for chess serves as an inspiring example for many. Rani Hamid’s three sons have also represented the country in various sports. Her eldest son, Kaiser Hamid, is a legendary football player. He played for the famous Mohammedan Sporting Club and the national team for over 10–12 years. Her second son, Sohel Hamid, is a former National Chess Champion and also represented the country in handball. Her youngest son, Boby Hamid, is a former renowned national handball player. Rani Hamid’s husband, Lt. Col. M. A. Hamid, was the founding president of the Handball Federation and received the National Sports Award in 1987.

In the chess community, Rani Hamid is not just a player; she is a pioneer who has navigated the complexities of gender dynamics within the sport. Her encounters with formidable opponents, such as Susan Polgar, showcase her resilience and determination. These experiences have only fueled her desire to continue competing and mentoring.

As she looks to the future, Rani remains optimistic about the potential of women in chess. With her ongoing efforts to motivate young players and engage their families, she is helping to create a brighter and more inclusive future for the game. Ultimately, Rani Hamid’s legacy will be defined not only by her victories on the board but also by her unwavering commitment to empowering women and inspiring them to carve their own paths in the world of chess. In doing so, she is ensuring that the game continues to evolve, welcoming new talent and ideas while celebrating the rich history and potential of female chess players everywhere.

A QUICK LOOK AT THE GAME OF CHESS

Whether or not you know how to play chess, it is likely that you have used chess analogies in your life. Maybe you have used phrases like – “I’m just a pawn in the game,” or “you’re playing checkers while they are playing chess,” or simply “checkmate.” Chess is often seen as a model for war, or any kind of battle. So pervasive is the influence of chess in our culture, that the ability to play chess is often equated with mental clarity, or a high IQ. So where does this game come from, and just how did it get so popular?

Perhaps specifics are hard to pin down, but it is said that chess was born in India before the sixth century AD. Known initially as Chutaranga, it spread through the region of Persia (what is now Iran) and then to the Arab world, where the term “Shah Mat” meaning “the King is dead” was used. And so we have the origins of a term recognized throughout the world as the definitive statement of victory: checkmate. Chess was very soon being played in Central Asia as well, as confirmed by archaeological finds in Uzbekistan. Around the year 1000 AD, chess invaded Western Europe, and in the late 1400s, it evolved to its current form, where the rules were formalized in a way that would be recognized today.

Today – those who play chess and those who do not play chess – all recognize immediately the pattern of a chessboard. The board comprises 64 squares which alternate between black and white. The white piece generally moves first, and this rule, observed to this day, goes all the way back to Renaissance Europe. The players each start with 16 pieces. There are eight pawns, two knights, two bishops, two rooks, one queen, and one king. Each of the pieces move uniquely: pawns, for example, move forward unless they are capturing a piece, in which case they move diagonally. The King can move only one square in any direction. The Queen, the most mobile of the pieces, can move horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, in any direction, for any amount of spaces.

While the basic rules of chess are simple enough, it goes without saying that getting good at chess involves aptitude for a certain type of thinking. It is often thought that chess players are simply innate geniuses, and while there may be some truth to that – after all, there are many child prodigies in chess – the fact is an immense amount of study and discipline goes into mastering the game. Memory and pattern recognition play a large part, as does the study of previous games. Chess players study a tremendous amount, from books analyzing patterns to websites that deconstruct famous matchups from the past. In this way, they build up tremendous repositories of knowledge inside their minds.

In today’s digital world, it is easy for a beginner to dip into the game. Matches can be played online, and a tremendous amount of learning resources are available at your fingertips. If your dream is to follow in Rani Hamid’s footsteps, the world of chess awaits you!

THE REAL QUEEN’S GAMBIT

Susan Polgar, born in Budapest on April 19, 1969, is a beacon in the chess world. At 15, she ascended to the pinnacle of female chess, a prodigy whose brilliance was undeniable. Polgar became the first woman to qualify for the Men’s Zonal World Chess Championship in 1986, when she was just 17. From 1996 to 1999, she reigned as the Women’s World Chess Champion, a testament to her strategic genius. In 1991, she shattered barriers, becoming the third woman to earn the Grandmaster title. Her legacy is not just in her victories but in her relentless promotion of chess, especially through the Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence (SPICE) at Webster University. Polgar’s influence transcends the board, weaving into the very fabric of chess education and advocacy.

TRIPLE THREAT

The Khadilkar Sisters—Vasanti, Jayshree, and Rohini—weren’t just chess players; they were a movement. Jayshree Khadilkar Pande, the torchbearer, became India’s first Woman International Master (WIM) in 1979. She dominated the Indian Women’s Championship four times, leaving a mark with a peak FIDE rating of 2120 in 1987. Vasanti Khadilkar Unni, with her graceful yet fierce gameplay, not only bagged the first Indian Women’s Championship but also jointly claimed victory at the 1984 British Ladies’ Championship in Brighton.

Then came Rohini Khadilkar, the youngest, yet the boldest of them all. She smashed records, winning the Indian Women’s Championship five times and the Asian Women’s Championship twice. Rohini also shattered another glass ceiling by becoming the first female chess player to win the Arjuna Award in 1980. Amidst these achievements, the sisters stayed grounded, helping their father manage Navakal, their family-owned newspaper. Their chessboard conquests played a pivotal role in advocating gender equality in sports, inspiring a generation of young girls across India to chase their chess dreams.

Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim

- Neha Shamim