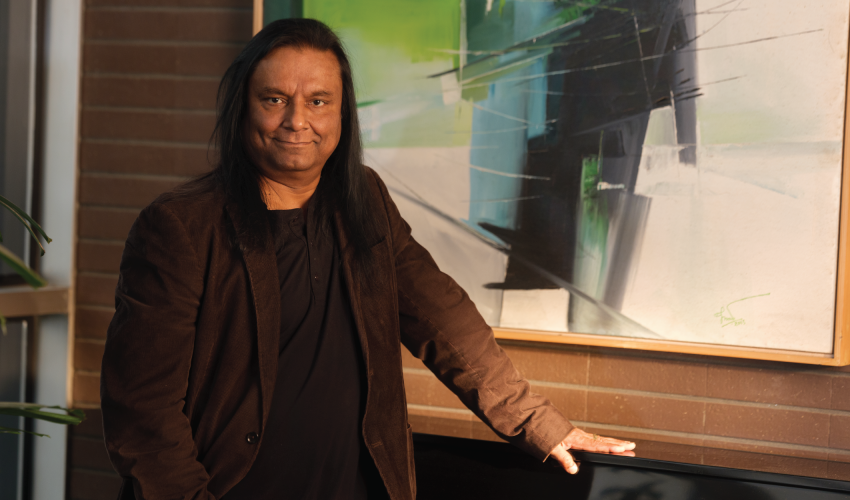

On a chilly winter afternoon, as the city of Dhaka moved to its usual rhythm, the MWB team arrived at the office of Vistaara Architects Pvt Limited in Gulshan. Inside the space that mirrored the man of the hour’s design philosophy – structured yet welcoming – Mustapha Khalid Palash greeted us with the calm demeanor of someone who has spent decades weaving art, music, architecture, and thought into a singular narrative. What followed was an in-depth conversation about his life, his work, and his perspective on the evolving architectural landscape of Bangladesh

By Ayman Anika

Mustapha Khalid Palash is not just an architect or an artist – he is a thinker who bridges the tangible and the abstract. His works – whether towering buildings or intricate paintings – are imbued with a sense of purpose, a deep reflection of the human experience.

His architecture speaks of bold forms and minimalist ideals, while his paintings reveal layers of emotion, often oscillating between harmony and conflict. For Mustapha Khalid Palash, creativity isn’t merely about aesthetics; it is a pursuit of meaning, a quest to connect the physical world with the philosophical one.

In a time when cities are growing rapidly but often without foresight, the architect’s voice stands as a call for balance – between progress and preservation, between innovation and respect for tradition. His journey, from a childhood steeped in art to becoming one of Bangladesh’s leading architects, shows how vision, rooted in integrity, can shape not only skylines but also conversations about identity and sustainability.

That afternoon, as we delved into his thoughts on architecture, it became clear that Mustapha Khalid Palash is not one to separate his craft from the world around him. For him, every design decision, every artistic stroke, is a response to a broader question: how do we live responsibly in a world that is constantly changing?

You grew up in a home surrounded by art, with both your parents being painters. Can you tell us about your childhood and how that artistic environment influenced you?

My earliest memory takes me back to 1965, during the India-Pakistan war. I dimly recall lying on my father’s chest, feeling the warmth of his embrace – a memory that marked the foundation of our deep bond. Time has an uncanny way of moving swiftly, and as I reflect on those days, it feels as though everything happened just yesterday or perhaps the day before. But the reality is, those moments were from a lifetime ago, yet their impact remains as fresh as ever.

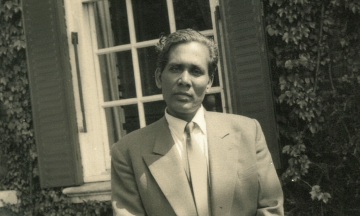

I was born in 1963 on Bailey Road, Dhaka. At that time, my father had recently graduated from what was then the Art College, now the Faculty of Fine Arts at Dhaka University. My mother was likely still a student there. As the second child and their first son, I suspect my father had a special fondness for me, which naturally strengthened our connection.

By the late 1960s, around 1968 or 1969, I was just five or six years old. I have vivid memories of holding my father’s hand as we joined torch-lit processions, chanting slogans like “Jeler tala bhangbo, Sheikh Mujib-ke anbo” (“We will break the jail’s locks and bring Sheikh Mujib back”). I can also recall sitting on the back of his motorcycle at dawn, heading to the Ramna Batamul to attend musical programs by Chhayanaut. Those early experiences with him shaped much of who I am. Until his last day, I remained inseparably attached to my father.

My love for drawing, I believe, was innate. My parents would often bring home small Maoist Chinese booklets from events celebrating Pakistan-China friendship, and I used these as my sketchbooks. It might seem unusual to imagine books becoming sketchpads, but that was our reality. At the time, being an artist meant living on the fringes of society. Financial struggles were constant, and buying a sketchbook for a child was considered a luxury.

Despite these challenges, my father found ways to nurture my interest in art. He worked at the Small and Cottage Industries Corporation and designed signboards for an insurance company on the side. At home, he would outline letters on the boards, and during the day while he was at work, I would fill in the colors. I was just seven or eight years old, yet my father trusted me with this responsibility. Trust, I have learned, builds confidence, and that belief in me was a cornerstone of my development. Over time, I became his assistant, learning nearly all the technical skills I know today under his guidance.

During the turbulent years from 1969 to 1971, I watched my parents actively participate in the independence movement, creating banners, posters, and alpana designs. Inspired by their dedication, I immersed myself in these artistic activities. After Bangladesh gained independence, drawing became more than a hobby – it became an obsession. Every day, I would draw after school until it was time to go out and play.

One poignant memory stands out. Seeing how deeply I was drawn to art, my parents stopped drawing altogether. It took me years to understand why. Practicing art in a struggling household was not just a luxury but an almost impossible endeavor. Yet, they made sacrifices, especially my father, to pass on their knowledge and skills to me. Their sacrifices remain etched in my heart.

By the time I finished school, I was already a budding artist. From designing alpana for February 21 commemorations to creating stage backdrops and Shaheed Minar models for my school, I embraced every artistic responsibility with enthusiasm. Alongside these, I was deeply involved in extracurricular activities like scouting, cultural programs, sports, and publications, all while excelling academically.

A defining moment in my life came in 1978 when I was in tenth grade. At the age of sixteen, I held my first solo art exhibition. Senior members of the Students’ Union, with whom I had been active since the sixth grade, encouraged me to showcase my work. The exhibition was inaugurated by the renowned artist Quamrul Hasan and attended by distinguished guests, including folklorist Professor Mansuruddin Ahmed and war hero Gazi Golam Dastgir, Bir Pratik. That event was a turning point, and from then on, everyone assumed I would pursue a career in fine arts.

However, the financial struggles of an artist’s life loomed large. My parents, having endured those struggles themselves, didn’t want me to face the same challenges. After finishing high school, I found myself at a crossroads. Despite my deep desire to study fine arts, my parents persuaded me to consider other options. I eventually took the admission test for Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology’s (BUET) Department of Architecture, ranking sixth on the merit list. Although my heart was heavy, my father reassured me, saying, “Architecture is also an art form, and an architect can be an artist too.” His words proved prophetic.

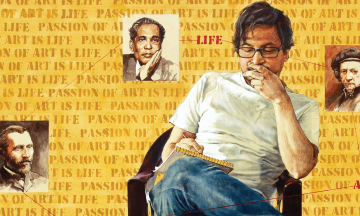

At BUET, I discovered how seamlessly art and architecture could coexist. I had the privilege of learning from legendary artists like Samarjit Roy Choudhury and Hamiduzzaman Khan, who served as co-instructors. Their guidance, along with the mentorship of other celebrated artists, nurtured my passion for art alongside my architectural studies. Years later, encouraged by Professor Hamiduzzaman Khan, I held my second solo exhibition in 2009 after a 30-year hiatus. This was followed by a third solo exhibition in 2011, inspired by Professor Nisar Hossain. Since then, I have participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions both locally and internationally, finding joy and purpose within the artist community.

Today, I feel immense gratitude for being part of this artistic family. While I never formally studied fine arts, the regret has diminished over time. As an architect by profession, I find profound happiness in identifying myself as an artist in thought and practice. The lessons, sacrifices, and love from my childhood continue to guide me, shaping both my art and my life.

As a child, did you always envision yourself becoming an architect?

Ever since I was a child, I had a natural inclination toward creativity and crafting. If I saw colors, I wanted to paint. If I saw a harmonium, I wanted to sing.

This desire was perhaps inevitable, given the environment I grew up in. I come from a family of artists, where art and creativity were a way of life. My elder sister sang Lalon’s songs beautifully, with a voice that could touch the deepest corners of the soul. My father played the flute with a gentle mastery, filling the air with melodies that lingered long after he stopped. My brother, on the other hand, had a flair for reciting poems with emotion and power. Each of them contributed to a home filled with artistic expression and inspiration. In such an environment, my own passion for art felt natural and inevitable.

My love for art found its first major milestone when I had my first solo art exhibition while I was in class 10. It was an extraordinary experience for someone so young, and it only strengthened my determination to pursue art as a career. At that time, I was euphoric, brimming with excitement and hope. I dreamed of a future where I would dedicate my life to art, creating works that would inspire and move people.

But as I grew older, reality began to set in. I saw my parents’ struggles first-hand – struggles that came with being artists in a world where art was often undervalued and economic stability was elusive. They worked tirelessly to support our family, but it was clear that the life of an artist was far from easy. Watching them navigate these challenges, I began to understand the difficulties that awaited me if I chose to pursue art as a career. My parents, deeply aware of these realities, gently discouraged me from following in their footsteps. They knew how much I loved art, but they wanted me to have a life where I wouldn’t have to constantly worry about financial instability.

It wasn’t an easy decision, but I eventually heeded their advice. With a heavy heart, I decided to explore other avenues. That’s how I found myself enrolling at BUET to study architecture. At first, I wasn’t sure if architecture could ever replace the joy and passion I felt for art. But as I delved deeper into my studies, I discovered something surprising – architecture, too, was a form of art. It allowed me to think creatively and design spaces that were not only functional but also beautiful.

Architecture became a new medium for me, one that combined my love for creativity with a practical approach to problem-solving. It taught me how to blend aesthetics with utility, and in doing so, it gave me a new perspective on art itself. While I was no longer painting or crafting full-time, I realized that the principles of art – balance, harmony, and expression – were deeply embedded in architecture.

Even as I pursued my career as an architect, I never let go of my passion for art. It remained a constant in my life, a source of joy and solace. Over time, I was able to craft a dual career, balancing my work as an architect with my identity as an artist. This duality has been incredibly rewarding, allowing me to explore the intersection of two fields that I love deeply. Looking back, I feel fortunate for the way things turned out. While my path wasn’t the straightforward journey I had envisioned as a child, it has been one of growth and fulfilment. I’ve had the privilege of combining practicality with passion, creating art in both traditional and unconventional ways. My dream of being an artist never really left me – it simply evolved into something broader and more dynamic.

Were there any specific mentors or figures in your early career who significantly influenced your creative vision?

My father. He has always been my biggest support, mentor, and friend. From a very young age, he not only nurtured my creativity but also taught me to see the world through a lens of curiosity and imagination. He was the one who introduced me to art in its most organic form.

When you founded Vistaara, what was your primary goal or vision for the firm?

As a matter of fact, Vistaara was founded in 1994 under the proprietorship of my wife, architect Shazia Islam and upon quitting BUET as Assistant Professor, Vistaara was enlisted as a limited company and I became the Managing Director of the company. Then I ventured into real estate as Development Entrepreneurs Limited, or in short, DEL. Later, we added “Vistaa,” which led to the name Delvistaa. Vistaara, on the other hand, is my consulting firm, and we also have the Delvistaa Foundation – a philanthropic organization that supports education and helps the underprivileged.

The turning point came when we won the competition for the People’s Insurance Company Limited building. Shortly after, I took on the Bashundhara City Shopping Complex project and decided to leave my teaching position at BUET.

The Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters is often celebrated for its modern design and functionality. And so is the Bashundhara City Shopping Complex. What were the key challenges in designing such large-scale commercial spaces?

Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters is a sustainable building in two ways. Grameenphone adhered to the tagline “Give more to earth.” From this idea, we created the entire building, and then we went on to win an international competition.

So, each project has been a different learning process for me – for example, Bashundhara City Shopping Complex has been a learning process for me in terms of technology and Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters has been another learning process for me in terms of sustainability. When we were working on Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters, we tried to see the concept of office building in a new light – as a workspace. We asked ourselves: How democratic could it be?

In a democratic once setup, as seen in some organizations like Grameenphone, there are no visible hierarchies. There’s no concept of “boss” or “subordinate” dominating the space. Everyone gets the same chair, the same table, and similar surroundings – what differs is job responsibility. It is a no-wall office. This design removes physical barriers, making the space more open and equal. The reasoning behind such designs is rooted in fostering collaboration. After that, we took more initiatives to break out of the conventional norms.

The pandemic highlighted issues in traditional office setups. Previously, most offices didn’t prioritize fresh air or ventilation. Fresh air is not just a luxury; it’s essential for life. Poor air quality can lead to exhaustion and negatively impact productivity. In most offices, there isn’t enough supply of fresh air and so, employees feel burnt out very easily.

However, in Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters, there is approximately 30% of fresh air. As per regulations, offices need to have around 12% of fresh air. So, you see, Grameenphone is doing far better in terms of indoor environment air quality (IEQ). We have addressed the six principles of sustainability. In sustainable design, there’s a balance between capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operational expenditure (OPEX). A good lifecycle cost analysis shows that investing in sustainable materials leads to long-term benefits. So, after considering all of these factors we have designed Grameenphone Corporate Headquarters. I have worked on some remarkable buildings, blending innovation with sustainability. I’ve completed 27 projects on Gulshan Avenue so far, starting from the Rangs Babylonia to projects like the Mobil House and the Eastern Bank. One notable innovation is how we’ve improved building e ciency. For example, we’ve added a structure detached from the main building – about 25 feet apart – serving as a screen, for shading purposes. The sunscreen is made from photovoltaic glass, which essentially acts as solar panels. It serves a dual purpose: first, shading the entire building, reducing heat gain; and second, it generates power. These see-through panels act as blinds, merging aesthetics with functionality.

Take the concept of the Mobil House as an example – it features a screen in front that enhances the building’s design while also shielding it from external heat. The straight wall design, combined with thoughtful detailing, makes it both sustainable and visually appealing.

Your designs frequently incorporate a cubic architectural style. How would you describe your signature style?

I would describe myself as a modernist. My designs often feature masculine elements, with a focus on clean, bold forms. I don’t believe in adding extravagance or unnecessary ornamentation – simplicity and functionality are at the core of my work.

I also draw inspiration from Brutalism, a minimalist architectural style that prioritizes the natural expression of materials and structures over decorative elements. It’s about letting the design speak for itself without relying on embellishments.

With urbanization increasing, what do you think architects can do to ensure green spaces and eco-friendly designs in Bangladesh?

Let me start with a story. I have an air purifier in my bedroom, and when I smoke a cigarette, it registers a pollution level of 36. However, the moment I open my bedroom window, the number jumps from 36 to 80. This stark difference highlights the alarming state of outdoor air pollution. If the air inside a closed room is cleaner than the air outside, it’s a grim reminder of what we’re living in. Imagine the constant exposure people face when they’re outdoors, especially those who have no choice but to work or commute in this polluted environment.

We often direct our blame toward cars, accusing them of contributing to air pollution. But what we fail to acknowledge is the massive pollution caused by air traffic. Every day, around 300 flights fly over our heads, burning jet fuel. The pollution caused by these flights is far greater than what a few vehicles on the ground can produce, yet this issue is often ignored.

Another major concern is the location of our airport. We’ve built it right in the middle of the city, surrounded by densely populated neighborhoods. What happens if a flight crashes? The potential for disaster is unimaginable. With such a high population density, the consequences would be catastrophic. Compare this with Malaysia, where its main airport is located 72 kilometers away from the city. They’ve ensured safety and minimized the impact on the urban environment. We could have adopted a similar approach, but instead, we prioritized convenience over long-term sustainability and safety.

The same lack of planning is evident in other infrastructure projects, such as metro rail stations and elevated expressways. These projects seem impressive on paper, but in reality, they fail to serve the majority. Who uses the elevated expressways? Only about 5% of the city’s population owns cars. The remaining 95% are left to deal with worsening tra c congestion, noise pollution, and lack of proper public transport solutions. We’ve created a system where a small elite benefits at the expense of the majority.

Now, let’s talk about greenery – or rather, the lack of it. We’ve systematically destroyed the cityscape without any conscious effort to preserve or integrate nature. Take the Moghbazar-Mouchak Flyover, for example. The people living below it don’t get sunlight anymore. They live in permanent shadows, surrounded by honking vehicles, pollution, and chaos. The air quality is abysmal, and the noise is unbearable. This is not progress; it’s a crisis. Dhaka is like a cancer patient, and instead of addressing the root cause, we’re trying to treat it with topical treatments. It’s heartbreaking to see what we’ve done to this city.

But while progress is inevitable, it doesn’t mean we should abandon nature. We don’t have to go back to living in caves, but we need gardens, big playgrounds, and spacious footpaths where people can walk safely and comfortably. We also need adequate green spaces between buildings to act as soaking grounds for rainwater. Without these, we’ve turned the city into a heat island. The lack of greenery and proper planning not only impacts the environment but also significantly affects our mental and physical health.

Architects and urban planners have a crucial role to play. They should strive to ensure that a city provides the minimum urban amenities that any civilized society deserves. This includes well-designed public spaces, efficient transport systems, and a healthy balance between development and nature. Sadly, these considerations have been sidelined. Ours is the only city in the world without proper traffic signals – a simple yet essential feature of urban planning. This isn’t just an architectural failure; it’s a systemic issue that reflects a lack of foresight and responsibility. We must rethink our approach to urban development. Progress shouldn’t come at the cost of our environment, safety, or quality of life. It’s time to make conscious decisions and build a future that prioritizes sustainability, inclusivity, and the well-being of all its citizens.

Outside of architecture, painting, and music do you have any creative pursuits that bring you joy?

I love collecting – whether it’s stamps, coins, or even boarding passes. These items hold sentimental value for me, as I see them as a way to store memories. Someday, I hope to share them with my grandchildren, telling stories about the times and places they represent.

I even once curated a library with books from the British Council. I can’t bring myself to throw those books away – they’re a part of my journey. You could say I’m a philatelist at heart, cherishing the beauty of preserving the past in tangible ways.

Lastly, what advice would you give to young architects aspiring to create?

Tough days are ahead for us. We may not notice it yet, but many of our key industries are gradually coming under the control of foreign entities, whether from neighboring countries or other parts of the world. Take the garment industry, for instance, or even the telecom sector –their influence is becoming increasingly evident and pervasive. Unfortunately, architecture is now facing a similar kind of invasion.

We have fought hard to elevate the standards of architecture in our country, often against significant odds. Yet, despite this progress, we seem to be moving backwards. Ours is a nation with a rich tradition of story-telling through art forms like patachitra and rickshaw paintings –deeply cultural and uniquely our own. But when it comes to architecture, we lack a deeply rooted identity that ties us to our heritage. This is where the problem begins.

Developers, in their pursuit of higher profits, believe that hiring foreign architects and contractors will automatically elevate the prestige and marketability of their buildings. They assume that this will lead to higher prices and better sales. But this is a misguided notion. How can foreign architects, unfamiliar with the nuances of our climate, culture, and traditions, truly design buildings that resonate with our context? Only local architects, who have grown up experiencing this environment, can understand the intricacies and deliver designs that are practical, sustainable, and reflective of our identity. This isn’t to say foreign architects lack skill, but they lack the understanding of our country’s unique needs. For instance, even in a neighboring country like India, I would say that apart from a handful of master architects, most others lack the vision to create something extraordinary. Their work often doesn’t rise to the level of being contextually or climatically appropriate. This should serve as a wake-up call for young architects in our country.

Our young architects need to be prepared to navigate these challenges. They must be ready to face the influence of foreign trends and practices and defend the relevance of local designs. The key to success lies in sincerity, integrity, and commitment to their craft. Studying architecture isn’t just about mastering technical skills – it’s about understanding the local climate, cultural context, and how modernist techniques can be adapted to create meaningful designs.

Another important lesson for young architects is to embrace simplicity. Avoid unnecessary extravagance in design. Architecture should serve its purpose without being burdened by excess. A good design is one that blends function, beauty, and sustainability seamlessly.

Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika

- Ayman Anika