InterContinental Dhaka has been part of some notable historic milestones in the formative years of Bangladesh

By Mohammad Atiqur Rahaman

“‘There is always a second bomb, I remember the King David in 47’ – I heard Clare Hollingworth urge the hotel guests to leave quickly just after a bomb blew up in the lobby while I was there to buy some smokes.” Remembering Hollingworth, the first English war correspondent to report the outbreak of World War II, described as the scoop of the century, Hugh David S Greenway, an American journalist of Washington Post, recalls a scene from the premises of InterContinental Dhaka (ICD), in August 1971.

From Spanish Civil war of the 1930s to the current ongoing conflict in Ukraine and Russia, hotels have played a pivotal role in war correspondence. During the Liberation War of Bangladesh, InterContinental Dhaka, referred to as “Dacca” at the time, was the sanctuary of choice for journalists covering the political turmoil between West and East Pakistan along with diplomats and other foreigners.

InterContinental Dhaka, previously known as “Hotel Inter-continental Dacca,” holds a remarkable legacy that encompasses the memories of the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, significant events from the Liberation War, and has a long-standing heritage of luxurious hospitality in Bangladesh since its inception. Throughout the war, InterContinental Dhaka witnessed significant historical events, including discussions on power handover after the 1970 election and the brutal genocide carried out by the Pakistani Army.

“In the name of God and a united Pakistan, Dacca is today a crushed and frightened city.” These are the indelible words written by Simon Dring, which captured the Pakistan Army’s brutal operations against unarmed Bengalis in East Pakistan during March 1971. It appeared on the March 30, 1971 issue of Daily Telegraph.

Could we imagine what would happen if the 27-year-old British reporter Simon Dring could not find sanctuary at the InterContinental to notify the world about the brutal genocide of Pakistani Army in Dhaka? It could have limited or slowed down media coverage, led to massive loss of evidence, and delayed international responses that would have significant implications to the struggle for liberation.

March 1971 marked a momentous period in the struggle for Bangladesh’s independence. It began with widespread protests on March 1, triggered by the decision of Pakistan’s military dictator, Yahya Khan, to indefinitely adjourn the National Assembly. In response, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman rallied the people and called for a non-cooperation movement. From that point until March 25, the movement for independence in East Pakistan steadily gained momentum through various incidents. Among these significant events, one that stands out is the memorable March 7 speech delivered by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman at Ramna race Course (now Suhrawardy Udyan) which Simon Dring listened to from the InterContinental Dhaka.

Dring was one of 35 journalists from the US, Australia, Britain, Canada, France, Japan, and Russia staying at Hotel Intercontinental to report on the impending constitutional crisis in East Pakistan sparked by Bangabandhu’s demand for independence. Until that moment, the world had not been paying much attention to the plight of the Bengalis. Pakistan was a strong ally of the US in the global politics of Cold War, and the US was providing substantial military aid to Pakistan in its fight against the spread of communism.

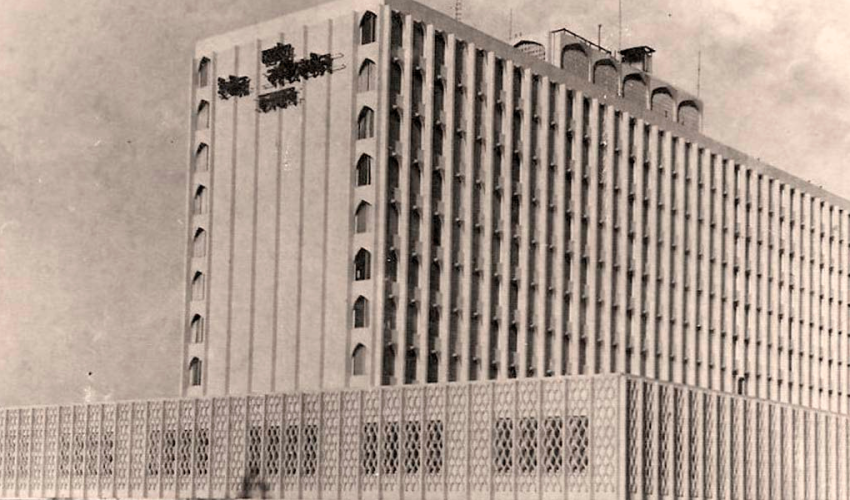

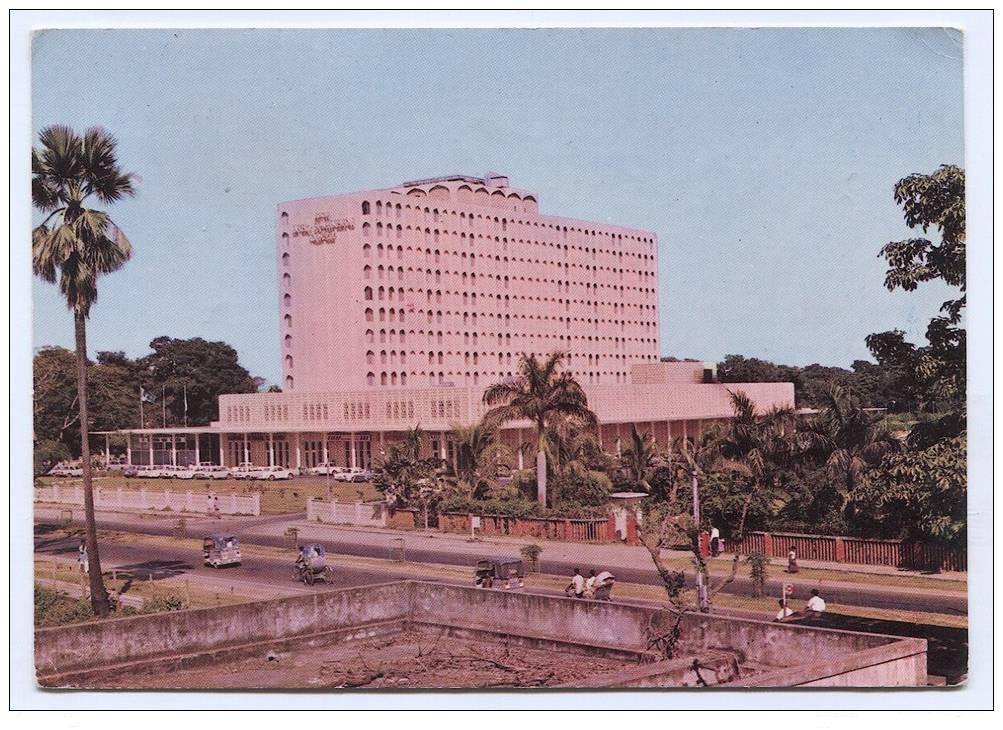

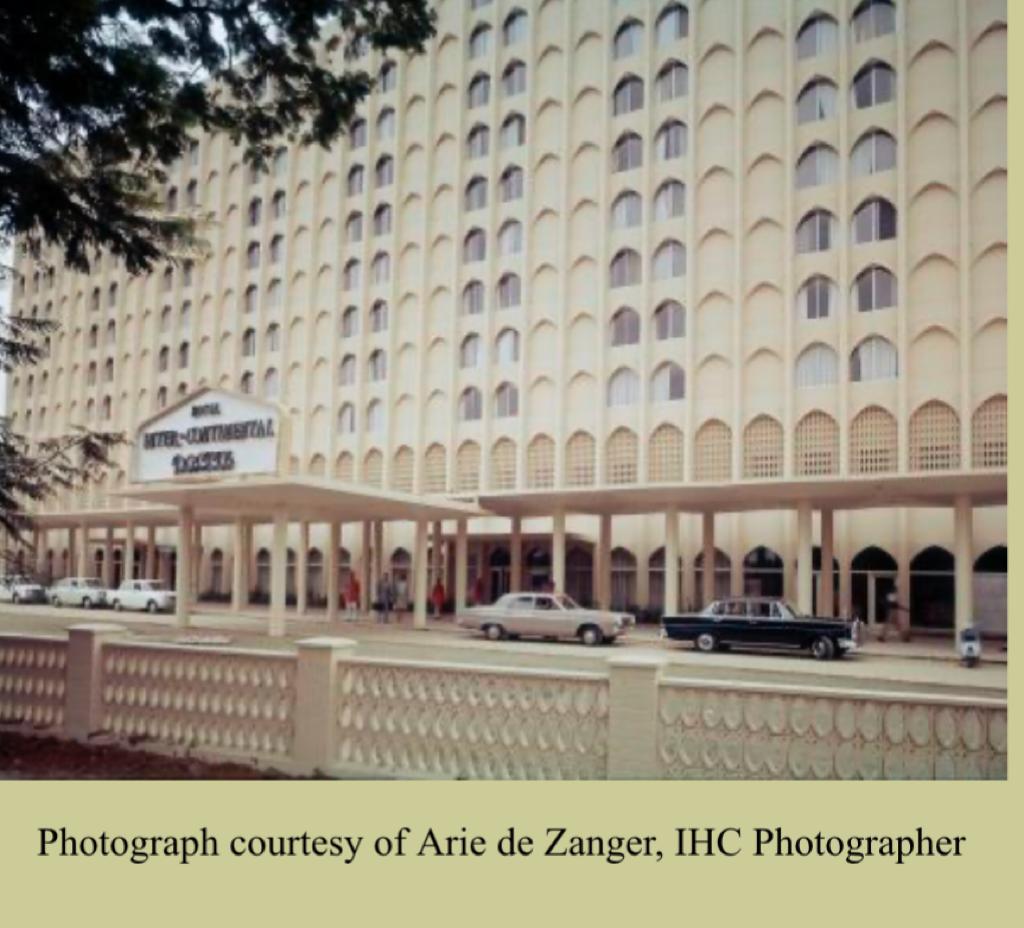

Earlier, on February 5, 1966, Bangabandhu publicly declared the Six Points, widely known as “charter of freedom for Bangladesh’s struggle for independence” in Lahore. Serendipitously, Hotel InterContinental in Dhaka commenced its operations on November 15, 1966. Famous American architect William B Tabler designed this iconic building and most of the original structure still stands today, notwithstanding the renovations over the years.

After winning the general elections in December 1971 with an unprecedented victory by Awami League, the first major talks over Pakistan’s political future took place between General Yahya and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in mid-January in 1971 in Dhaka. President Yahya Khan, before leaving for West Pakistan, affirmed the accuracy of Bangabandhu’s statements about their discussions, acknowledging him as the future prime minister of the country.

ICD gained political significance when Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), visited Dhaka with his team for three days of negotiations starting from January 27, 1971, at InterContinental Dhaka. However, these discussions turned out to be unproductive, lacking any meaningful results. On February 15, 1971, ZA Bhutto announced that the PPP would not attend the National Assembly session in Dhaka due to the unlikelihood of reaching a compromise on the six-point declaration by Bangabandhu. Consequently, President Yahya Khan postponed the National Assembly session on March 1, 1971, leading to massive protests in Bangladesh.

The hotel garnered attention again when Bhutto returned to Dhaka next month to participate in ongoing negotiations between Bangabandhu and President Yahya. While the President stayed at the President’s House, Bhutto’s team stayed at the ICD. However, outside the hotel, a group of Bengalis protested by shouting slogans against Bhutto and displaying their disapproval by showing him their shoes.

In the evening of March 25, 1971, President Yahya Khan unexpectedly departed from Dhaka to Karachi, leaving negotiations with his team and Bhutto unfinished. Prior to leaving, he informed General Tikka Khan, the zonal martial law administrator, that military operations would commence that night, but only after he had safely arrived in Karachi. This information was then relayed to General Khadim Hussain Raja. At midnight, the Pakistan army launched a brutal crackdown on unprotected civilians at midnight, resulting in one of history’s most horrific massacres, infamously known as Operation Searchlight on the then provincial capital Dacca which marked the beginning of a nine-month-long armed conflict that eventually led to the birth of an independent Bangladesh.

The journalists stationed at ICD passed a busy day covering the Bangabandhu- Bhutto talks. Little did they imagine the horrors that would soon unfold. One imagines them unwinding in the evening after filing their reports, when they heard the terrifying sounds of tank, guns, and machine-guns. Confused and perplexed, they sought information from the soldiers stationed at the hotel, only to be met with vague answers regarding threats of violence. A group of reporters then decided to approach the 11th floor, where Bhutto was residing, in order to inquire if he had any knowledge or insights into the shooting incident.

According to Robert Kaylor of United Press International (UPI), during the massacre, Bhutto’s bodyguards stood in the hotel’s 11th floor hallway with assault rifles. A member of Bhutto’s political party arrived and claimed to have no knowledge of the situation. He also revealed that Bhutto was sleeping, and the instruction was to awaken him at 7:30am.

Another guest, Sydney H Schanberg of The New York Times, stated that the officers in the hotel denied information to journalists and their attempts to contact diplomatic missions failed. In a confrontational incident, an armed captain angrily ordered some journalists, who walked out the front door to talk to him, to go back inside and warned them that “if he could kill his own people, he was also capable of doing the same to them.”

It is reported that a number of journalists and guests staying at ICD saw the nearby office of the Daily People, an English newspaper known to be critical of the military regime, being destroyed with mortar shells and bomb attacks.

On March 26, Major Siddique Salik, the Pakistan Army’s PRO, arrived at the hotel InterContinental and issued a directive for all foreign journalists to leave the city by nightfall. The motive behind this order was to conceal an ongoing genocide taking place in the region. The Pakistan Army aimed to prevent the international community from uncovering their actions, fearing that their major military aid provider, the United States, would withdraw support if they discovered the military’s misuse of weapons against civilians. In order to ensure that the journalists remained unaware of the atrocities occurring, the Pakistani military forcefully gathered them early the next morning and transported them to the airport, where they were placed on a plane destined for Karachi. According to Schanberg, the departure from the hotel to the airport occurred at 8:20am. The convoy involved five trucks, guarded by soldiers at the front and rear. Around 50 journalists from various countries, residing on different floors of the InterContinental, witnessed the brutal genocide on the night of Thursday, March 25. However, they were compelled to depart Dhaka without adequate documentation and evidence of the savage assault perpetrated by the Pakistani Army.

At the airport, the journalists’ luggage underwent thorough inspections, and certain television footage, notably from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), was seized by the Pakistani army. In addition, the journalists themselves were subjected to full body searches before boarding the plane. These measures were taken to prevent the journalists from taking out any audio or visual evidence of the violence and destruction they had witnessed during the genocide.

We are now privy to this information because Simon Dring and Associate Press photojournalist Michael Laurent risked their lives by hiding behind the main air condition units on the roof of the hotel InterContinental for more than 32 hours. Despite knowing about the bloody holocaust on a freedom-seeking nation on that night, the other journalists had to leave Dhaka and none of them could carry any information and evidence of the genocide, except Simon and Michael.

Simon and Michael hid in different areas of the Intercontinental Hotel for 32 hours. When the curfew ended on March 27, 1971, they bravely ventured outside, disguised in traditional attire, to document the situation in Dhaka. They toured the city extensively, capturing disturbing details of the brutal acts that took place at Dhaka University, Rajarbagh Police Line, and parts of old Dhaka. Although they were spotted by a Pakistani army patrol at Iqbal Hall, they managed to escape capture. The officers, however, became aware of the presence of Western journalists. They later searched the hotel, but the fugitives were concealed by the local staff, allowing them to evade capture again. As the situation worsened, Simon and Michael decided to leave the country. They flew out of Dhaka to Bangkok, and were finally able to share their firsthand account of the genocide with the international community. Simon left Dhaka after March 26 and filed a special report from Bangkok, providing a detailed account of the sudden and widespread crackdown. Another boarder, Arnold Zeitlin, Associated Press (AP) bureau chief in Pakistan, had been able to avoid army confinement as he was out of hotel that night and he found Simon and Michael at ICD.

On March 27, when the curfew was lifted, Simon and Michael, disguised as kitchen staff, left the hotel and travelled the city on the back of a baker’s van and collected the evidence of genocide in the city. At Dhaka University, Simon discovered the bodies of around 30 students near Iqbal Hall, an art student sprawled across his easel. Nearby, a lake held floating corpses, while others near Jagannath Hall were cruelly disposed of in hastily dug graves destroyed by a tank. Tragically, seven teachers and a family of 12 lost their lives in their respective living quarters. He also witnessed extensive destruction in the narrow streets of the old city, where areas were burned down, and innocent people were dragged out from their homes and shot. Shockingly, at the Rajarbagh Police Lines, tanks were used to support troops who cruelly fired incendiary rounds into sleeping quarters, resulting in the devastating loss of over 1,100 police officers.

Later he managed to board on a flight to Karachi with his reports and smuggled his evidence until he reached Bangkok. The famous report by Dring titled, “Tanks Crush Revolt in Pakistan” was published in the front page of The Daily Telegraph on March 30, 1971 and is considered as the first report in the international media of the brutal genocide in Bangladesh. It is clear that his news and photographs by Michael Laurent exposed the truth for the first time to the international media about what really happened on the night.

Later, Arnold Zeitlin claimed to be the first journalist to report on the crackdown by the Pakistani Army outside East Pakistan. He, along with Simon and Michael, were on a PIA flight that made a stop for refueling. Arnold took the opportunity to leave the plane and contacted AP stringer Manik De Silva in Colombo, dictating the facts to him. The news was later published in The New York Times under the title “Army in Control” on March 28, 1971. However, the article did not provide a clear description of the brutality inflicted upon unarmed civilians by the Pakistani Army on March 25, midnight.

According to a report by Sydney Schanberg, titled “In Dacca, troops use artillery to halt revolt” published on March 28, 1971 in The New York Times, when the newsmen attempted to go outside to gather information about what was happening, they were stopped at the gate and were threatened to be shot. Later on, the firing intensified around 1pm, and approximately 25 minutes later, the phones at Hotel InterContinental went dead. He also stated that the confined journalists watched from the hotel flames from Dhaka University and the army seemed to be shooting artillery.

When Indian Army joined in the Liberation War of Bangladesh against the Pakistani Army, International Red Cross designated Hotel InterContinental as a neutral zone. After the crackdown, ICD turned into the temporary office of the United Nations in Dhaka and provided spaces for international media including BBC, Reuters, AP, and AFP. As Indian and Pakistani air force jets engaged over Dhaka city, the hotel management had to remove shrapnel from the swimming pool with magnetic fishing poles, recalls reporter Jim Sterba of New York Times.

The employees of ICD actively participated in the Liberation War, directly or indirectly. Two of these dedicated employees, Khwaja Nijamuddin Bhuiyan, Bir Uttam, and Osman, made the ultimate sacrifice and embraced martyrdom during the war.

On June 9, 1971, the Crack Platoon, a specialized commando unit of the Mukti Bahini, carried out their first guerrilla operation at ICD in Dhaka. The objective of the mission was to disrupt the World Bank Aid Mission and prevent Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, the leader of UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), from providing financial assistance to the Pakistani regime.

Meanwhile, the Pakistani government’s media cell falsely portrayed East Pakistan as stable and in need of economic aid from the international community. Equipped with ENERGA grenades, bayonets, and sub-machine guns, the Crack Platoon initiated the attack by ambushing a car in front of the hotel. They threw a total of five grenades during the operation, resulting in the deaths and injuries of several Pakistani soldiers. The BBC extensively covered this significant event, which gained widespread attention in the international media, revealing that the situation in Dacca (now Dhaka) was far from stable.

During that period, the InterContinental Hotel accommodated journalists from various countries, including Mark Tally from the BBC, whose presence became intertwined with the memories of the hotel and the Liberation War. They, continuously provided the world with the latest updates on the war, shedding light on the extreme cruelty and annihilation carried out by the Pakistani military against the Bengalis. These reports began to shape global sentiment against Pakistan. Journalists began questioning the State Department during press briefings regarding the use of American weapons against civilians. The US Congress even initiated discussions on the United States’s involvement in the war. The majority of public opinion worldwide decidedly leaned in favor of the Bengalis.

While high-ranking officials gathered at the hotel lobby to exchange information, ordinary citizens were seen assembling on the sidewalks across the roads, eagerly awaiting updates from the warzones. The nine-month-long struggle for independence, initiated by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, reached its conclusion on December 16 when the occupying Pakistani army surrendered near Suhrawardy Uddyan, situated in the vicinity to the InterContinental Hotel.

This hotel has been a symbol of safety and significance from March 25, 1971, when the ruthless assault on innocent Bengalis commenced, until the victory in the war on December 16 of the same year. The events that occurred around the premises of InterContinental of those days in 1971 are a significant chapter in the historical narrative of Bangladesh’s struggle for independence. For all these, InterContinental Dhaka, as an institution may deserve the Swadhinata Padak.

After independence, the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, realizing the prospect of the hospitality industry, formed Bangladesh Services Limited as a public limited company to conduct hospitality business and assigned responsibility to manage this state-owned hotel. Since then, Bangladesh Services Ltd has been delivering hospitality services of international standard successfully through partnerships with well-known international hotel management companies.

Time passes by, InterContinental Dhaka stands as the reminder of a chronicle of one of the most significant events of the last century.

The writer is Managing Director (Joint Secretary), Bangladesh Services Limited.

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema

- tarin fatema