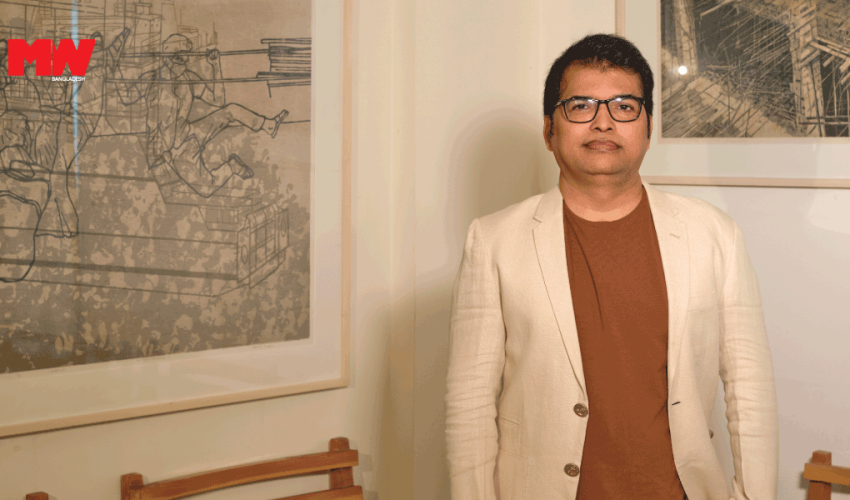

The artistic Odyssey of Anisuzzaman Anis

By Anika Chowdhury

As an eminent Bangladeshi artist and a distinguished professor at the Department of Printmaking of Dhaka University, Anisuzzaman Anis has carved his path as a maestro of engraving. He is not merely a revered teacher but is also sculpting dreams into reality through the unique artistry of woodcut prints. His journey – like the intricate lines of his woodcuts – is filled with depth and expression.

Anisuzzaman Anis embarked on his artistic odyssey with a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts (BFA) in Printmaking from the prestigious Dhaka University in 1993. His artistic prowess was evident early on, securing him the coveted First-Class 1st position in his graduating class. His passion for learning further encouraged him to get a Master’s in Fine Arts (MFA) in Printmaking from Rabindra Bharati University in Kolkata in 1997 – again achieving First-Class 1st position!

The pinnacle of Anisuzzaman Anis’s educational journey was his Master of Fine Arts in Printmaking from Tama Art University, Tokyo in 2008. This international exposure marked a transformative phase in his artistic career, blending the precision of Japanese printmaking with the diversity of his Bangladeshi roots.

Under the tutelage of Japanese masters, he delved into the profound world of woodcut prints, an ancient technique that would become the cornerstone of his distinctive artistic identity. The intricate dance between the chisel and wood and the meditative strokes that bring life to the grain all became part of this brilliant scholar’s artistic DNA.

From the bustling streets of Tokyo to the cultural hubs of London, his work has resonated with audiences worldwide. As MWB joined Anisuzzaman Anis on a Google Meet call, he walked us through his creative journey that spans over decades.

What inspired you to embark on a journey into the world of fine arts, and were there any pivotal moments that shaped your decision?

It is not easy to be a creative person and you need to have passion and devotion towards your art. This is true not only for painters but also for every artist, who is dedicated to fine arts – and I had that love and admiration for art from a very young age.

To be an artist has been a call for me.

I started drawing when I was in my school years; my works were featured in wall magazines published in my schools. My teachers were impressed by my work and they encouraged me to get admitted to art school, which we now recognize as the Fine Arts Department.

These special recognition and extracurricular activities further ignited my interest and I eventually sought guidance from one of my seniors, Abdul Ahed – a student of the Department of Ceramics at Dhaka University. It was the year 1988, the entire country was flooded and our lives were in disarray; nevertheless, I came to Dhaka and attended coaching classes for my entrance exam.

My only goal was to get admitted into the Department of Fine Arts and luckily, I passed the entrance exam and went to study at Dhaka University. Many students go on to sit admission tests in numerous universities but my sole focus had been to achieve a fine arts degree and I eventually accomplished my goal.

I wholeheartedly cherish the years I have spent at Dhaka University. Here, I found myself immersed in a melting pot of creative energies, guided by passionate mentors who nurtured my budding talents. The rigorous training in printmaking became a gateway for me to explore the intricate dance between tradition and innovation.

Can you share insights into your formative years as an artist?

I used to dream about studying in an art college from a very young age. The culture, people and environment of an art college fascinated and my passion nurtured my imagination. I found myself irresistibly drawn to the kaleidoscope of colours and structures that surrounded me.

And so, with my dedication and hard work, I was able to get admitted into the university – achieving the First-Class 1st position in 1993. After graduating, I received The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) scholarship and went on to study MFA in Printmaking at Rabindra Bharati University, graduating with a First-Class 1st position.

Frankly, my journey truly took flight during my time at Dhaka University. Here, under the watchful eyes of mentors who were not just educators but custodians of creativity, I began to mould the clay of my artistic identity.

We didn’t have many printmaking tools to work with – most of our work was done with the help of anti-cutters. One memory that is still ingrained in my mind is the compliment I received from the esteemed artist Safiuddin Ahmed. One day, I was working with an anti-cutter and Sir Safiuddin Ahmed saw my work and praised it. His words meant the world to me. That said, I am grateful to my teachers and mentors namely cartoonist Shishir Bhattacharjee and Professor Mahmudul Haque, who have supported me and guided me with proper instruction.

Reflecting on your learning days in Japan, how did the cultural and artistic landscape influence your artistic perspective, and what specific techniques did you adopt during that period?

An important chapter in my artistic evolution was the exploration of Japanese artistry. But before going to Japan, I was engaged in a six-month residency programme at Glasgow Print Studio and London Print Studio, UK in 2004 as I was a recipient of the Commonwealth Arts Scholarship.

The Glasgow Print Studio and London Print Studio residencies in 2004 were akin to artistic pilgrimages, allowing me to soak in the vibrancy of the European art scene. These experiences became crucibles of creativity, shaping my understanding of the universal language spoken by artists across borders.

Then, I delved into woodblock print research under the esteemed guidance of Prof. Keisei Kobayashi at Tama Art University, Japan. It was a transformative experience for me and these encounters with a different cultural ethos not only refined my technical skills but also infused my work with a global perspective, creating a symbiosis of my Bangladeshi roots and the precision of Japanese artistry.

While staying in Japan, I had the opportunity to observe the Ukiyo-e masterpieces – a genre of Japanese woodblock prints and paintings produced, featuring motifs of landscapes, tales from history, the theatre, and pleasure quarters.

From the water media, and oil media to the ins and outs of printmaking, the knowledge I gained from Japan has blessed me with a fresh and more polished perspective.

As someone who has experienced both Bangladeshi and Japanese fine arts scenes, what notable differences do you observe between the two, and how has this cross-cultural exposure influenced your work?

Japan is starkly different from Bangladesh and the differences between the two are not merely aesthetic but extend to the very essence of artistic expression, shaping the lens through which I approach my craft.

I would say Japanese people are very disciplined and focused on their goals, a trait we need to nurture among ourselves. For example, we are acquainted with the work-from-home culture whereas Japan adopted such a practice many years ago and they are not tardy but rather a proactive nation. They are far more advanced than us and we have a lot to learn from them.

The Japanese fine arts scene is characterised by meticulous precision and a profound reverence for craftsmanship. The minimalist aesthetic and the disciplined approach to technique contribute to a unique artistic ethos. This exposure has instilled in me a heightened sense of precision and meticulous attention to detail.

Woodcut prints are a distinctive part of your artistic repertoire. Can you provide insights into the themes or subjects that you explore in your work?

The theme of realism permeates my woodcut prints, as I strive to capture the essence of everyday life in its unfiltered beauty. Realism becomes a vessel through which I communicate the stories of my people, their struggles, and their triumphs.

The influence of Fumiaki Fukita is palpable in my works, particularly in the meticulous attention to detail and the nuanced exploration of form. Additionally, the infusion of diffused light in my woodcut prints pays homage to the profound impact of Louis I. Khan’s architectural philosophy. The interplay of light and shadow, a hallmark of Khan’s designs, finds its way into my compositions, creating a play of mood and atmosphere.

Every artist and their styles differ from one another and mine rely on the fibre, which is the main character of woodcut. Essentially, I try to keep the main form and texture intact and work with the fibre.

Beyond academia, where do you see opportunities for young graduates in fine arts to contribute meaningfully to society, and how can they navigate the diverse career paths available?

Of course! There are many options available for the youths to venture towards. We now have many departments such as graphic design, motion graphics, animation and whatnot. I have seen people in Japan graduating from fine arts and starting their own businesses; people there have taken up jobs not related to this subject namely a police officer, and banker. They are people who are freelancing and are working happily.

As a professor at Dhaka University, how do you balance your roles as an artist and an educator?

I am an educator as well as an artist and in Japan, I learned that first I learn by myself then I will be able to teach others. This is the philosophy I have been following. I practise work diligently as an artist but when one of my students does well, I become elated as a teacher. This is how I find satisfaction in work and keep moving forward as best as I can.

Looking ahead, what future projects or artistic endeavours are you excited about?

I want to keep encouraging my students to continue practising not only woodcut or printing but also art itself. I want to keep experimenting as I am a visual artist and I cannot confine myself to one single medium. Right now, I am working with acrylic medium but at the same time, I am excited to see where my experimentation will take me.

Phtotographed by Adnan Rahman