By Ayman Anika

Some actors burst into the scene like firecrackers, loud and momentary. And then there are artists like Tama Mirza—quiet, steady, persistent—who don’t arrive with noise but with presence. You don’t remember the exact moment you first saw her on screen. But somewhere between a glance, a gesture, a shift in breath, you begin to notice her. And once you do, you keep watching.

Tama Mirza’s story doesn’t follow the well-worn script of stardom. There was no overnight breakthrough, no industry godfather, no splashy debut. Instead, there was a girl from Bagerhat, who came to Dhaka for college, stumbled onto a film set, and found herself strangely drawn to the act of performing—despite believing, in her own words, that she had “acted terribly.” And that might be what defines her most: the ability to look at her own work with brutal honesty, and the desire to keep learning anyway.

With MWB, Tama opens up about her earliest dance lessons at age three, her sleepless nights balancing exams and shoots, her rural upbringing and urban readjustment, and the moment she received the National Film Award without even knowing she’d been nominated.

Were there any moments or memories from your childhood that, in hindsight, hinted at your love for performance?

Yes… well, it’s a bit of both—yes and no. My earliest introduction to performance, I suppose, was through dance. I was around three and a half, maybe four years old. I had just begun learning to count—one, two, three, four—and that’s when my journey quietly began. My father used to take me to dance classes back then. Of course, I was too young to follow a structured curriculum or understand any technicalities, but I was there, soaking it in.

Soon after, I started going to music classes too. I didn’t sing much, though—I’d mostly just sit there and listen. But that environment left an impression. I also tried my hand at reciting poetry, dabbling in painting… honestly, I was involved in everything creative. Both my parents were very culturally inclined, and they noticed that I had an interest in the arts. So they made sure I had access to good teachers from a very young age. They didn’t push me—but they gently guided me toward things I seemed to enjoy.

I kept learning music until about class five, but at some point, I realized singing didn’t truly call to me – it didn’t bring me the joy that dance did. Dance, on the other hand, always felt alive to me. It stayed with me, and I kept growing with it.

Even now, when I come across a new dance move—whether in a film or just scrolling online—I instinctively try it. If I don’t get it right, I try again. That same curiosity from childhood is still there. So yes, in hindsight, that early exposure to dance, to rhythm and movement, probably planted the first seeds of my love for performing. And I’ve been learning ever since.

Before a shoot, I usually detach. I go inward, I watch films, I think deeply about my character’s world.

You moved to Dhaka quite young. What were your early struggles?

I completed my SSC in Bagerhat—that’s where I spent most of my childhood. So, coming to Dhaka was initially a practical decision. I moved here for my HSC studies with the hope of getting into a good college, and eventually a good university. My mother and younger brother moved with me, while my father—who had a government job—stayed back in Bagerhat due to his posting. My brother was very young at the time—he’s 11 years younger than me—so part of the reason for shifting was also to enroll him in a good school in Dhaka. In a way, we were trying to expand our canvas.

Back then, coming to Dhaka felt like a big deal. Honestly, I had only been to Dhaka twice before the move—it felt as exciting as a foreign trip might feel now. I remember one of those visits very clearly—we went to FDC (Film Development Corporation), and I was just a curious visitor. I saw a few celebrities, took pictures, and felt a kind of awe. But at the time, the idea of becoming an actress never crossed my mind. It seemed like an impossibly distant dream—something that required a lot of talent, a lot of struggle. To me, a “star” was someone almost mythical.

Then, after we moved to Dhaka, something unexpected happened—I received an offer for a film. At first, my family wasn’t on board at all. My parents, especially my mother, were very clear: “We supported your interest in singing and dance, we even arranged teachers for you. But now is the time to focus on your studies. Once you enter the film world, there’s no going back. Your studies will suffer—and in our family, education has always come first.”

But I was curious. I wanted to try—just once. I didn’t have any relatives in this industry. No uncles or cousins in the film. And this was a big opportunity, even if it was a small role. I told my maternal aunt that I wanted to do it, and together, we convinced my parents. That was how my first film happened.

In that film, I wasn’t the lead—I played the second lead alongside another co-actor, while the main hero-heroine were a different pair. But that experience changed something in me. I had never acted before. Whatever little performance I had done was through expressions in dance. So, this was entirely new. And I won’t lie—when I saw my performance on screen, I thought it was quite terrible. But even then, I felt a strange excitement. A hunger to learn. That’s something I’ve always had in me—if I see something that interests me, I want to understand it, get better at it.

After that first film, I did another one, and then another. That’s when I slowly started thinking—maybe this could be something more. Maybe this could become my profession.

But that’s also when the real struggle began.

There were two fronts to it. First, I had to manage my education alongside my growing film work. I remember during my HSC, I was shooting while preparing for exams. I’d study all night, sit for my exam in the morning, and then head straight to the shooting set. Sometimes the car for the shoot would be waiting outside the exam center. I’d shoot until midnight, return home, study again, and repeat the whole cycle the next day. It was exhausting—but I pushed through. I was a good student, so thankfully I didn’t fall behind or fail.

The second, and more difficult struggle, was within the film industry itself.

I had started with second lead roles, and climbing up from there to become a lead actress was incredibly hard. I also felt very out of place. Coming from a rural background, I didn’t understand the industry’s language—makeup, styling, costumes, how to carry yourself, how to perform for the camera. I constantly felt like I wasn’t “screen-ready.” I wasn’t getting strong characters, and when I did act, I wasn’t satisfied with my own work. I knew I was falling short.

Then came Ek Mon Ek Pran by Sohanur Rahman Sohan. That film was a turning point. It was on that set that I really learned something—how to dub, how to perform with more intention. And when it was released, people finally started to notice. “Who is this new girl?” they asked. Even though I had already done two or three films before that, no one really knew me.

That was followed by O Amar Desher Mati (2012), where I finally played a lead role. And then came Nodijon (2015), which got me the National Award. So yes, I was progressing. But even after all that, people didn’t fully see me as a lead actress. I hadn’t really “arrived” yet in the public eye.

Meanwhile, my university studies were falling apart. I had to take a two-year break. Every time a mid-term came around, I had a shoot scheduled. And by then, acting had become my bread and butter—my main source of income. I had to make a choice.

That’s when my family really stepped up. They told me, “Take a break from films. Finish your studies. And use this time to prepare, because you’re still struggling. You’ve won a National Award, but you haven’t yet been recognized as a heroine—or even as a serious actress.”

So, I took that break. And I worked on myself—mentally, emotionally, professionally.

That entire journey—moving from Bagerhat to Dhaka, juggling exams and shoots, slowly climbing from second lead roles to national recognition—it was anything but smooth. But each struggle taught me something. And each pause prepared me for the next chapter.

Nodijon (2015) earned you the National Film Award for Best Supporting Actress. What did that recognition mean to you at the time?

Honestly, when I received the National Award, I had absolutely no expectation. I didn’t even know that my name had been submitted for Nodijon, or that I was being considered for any nomination. So, when I eventually found out that I had actually won, it was surreal.

It felt extraordinary to me because I came from a small rural background, and I had been struggling continuously to find a stable footing in this industry. To suddenly receive national recognition—it was an indescribable feeling. That moment felt bigger than me. It was emotional, humbling, and deeply validating all at once. I still remember thinking: “A girl from Bagerhat, who knew no one in films, has received this honour.” It gave me the kind of strength and hope that words can’t really capture.

The National Award, for me, worked as both a booster and a mirror. It gave me confidence that yes, I can do this. I do have some talent, and I just need to keep trying. It reminded me that perseverance pays off. But at the same time, it was bittersweet. Because even after receiving that recognition—the biggest award in our film industry—I wasn’t getting the kind of projects I wanted.

You know how, ideally, an award becomes a ladder—you climb a little higher, step by step? For me, it wasn’t like that. I was standing exactly where I had been before. I had the National Award in my hand, people were appreciating me, calling me a good actress, but the kind of substantial, challenging roles I longed for just weren’t coming my way. I felt as though the audience hadn’t yet accepted me in the way I hoped they would.

That’s when I decided to take a step back and refocus. Around 2018, I completed my graduation. From 2018 to 2019, I took a proper break from work. I had done a film in 2017, but after that, I completely paused to rebuild myself—mentally and professionally.

When I came back in 2020, I returned with a different mindset. And looking at these last five years—from 2020 to now, 2025—I truly feel like this has been the real beginning of my career. These five years have been about growth, control, and clarity. I’ve finally been able to shape my journey the way I always wanted.

Everything before that—the six, seven, maybe even eight years—feels like a long period of learning. It was all experience, trial, and error. I don’t regret any of it. I never blame anyone—not the industry, not the so-called “film politics.” Instead, I try to look inward. I had my own limitations back then, my own areas of weakness. And over time, I’ve turned those into lessons.

Collecting those small experiences, one after another, has built me into who I am today. And now, when I hear people—colleagues, co-actors, or even the audience—say, “Tama Mirza is a really good actress,” that makes me feel proud in a very grounded way. That’s the validation I was chasing, not just awards or titles, but genuine respect for my craft.

So yes, the National Award was a turning point—but not because it made me “arrive.” It reminded me to keep climbing, even when the ladder seemed to stop. And today, I feel I’m finally moving upward, step by step.

A girl from Bagerhat, who knew no one in films, has received this honour—it was an indescribable feeling.

You’ve worked in both mainstream cinema and OTT content—what have each of them taught you?

For me, OTT has been like my preparation ground—or to put it more precisely, my mid-term exam. I often use this analogy in interviews, and I truly believe in it. During my student life, I always found midterms more intense than finals. There was so much pressure—because if you failed the mid-term, you couldn’t sit for the final. So, I would prepare rigorously for it. And when I passed that stage, my confidence would rise. The final exam, by comparison, always felt a bit easier because I had already overcome the real mental hurdle.

In the same way, I see OTT as my mid-term, and big-screen films as the final exam. OTT projects may not have massive sets or star-studded ensembles, and they might not release on the silver screen—but that doesn’t make them any less important. In fact, they’re incredibly important to me. I take OTT work very seriously. Every time I’ve done an OTT project, I’ve treated it like a lab for self-exploration.

If you look at my OTT performances, you’ll notice I’ve experimented a lot. I’ve tried to take on characters that are different from each other. I’ve broken myself down, emotionally and mentally, for those roles. That space allowed me to test my range, push my boundaries, and learn how to be more honest with my performances.

So when I got a chance to do something like Jerin in Daagi, or Moyna in Surongo, I already felt ready. It’s because of that groundwork—the preparation I had done through OTT—that I could give my best on the big screen. Those performances weren’t just spontaneous. They were built on the foundation I had laid quietly in the OTT space.

Honestly, I feel I need an OTT role before diving into a big film. It helps me get into the zone. It sharpens me. It reminds me of who I am as an actor. So yes, OTT has been crucial—not as a stepping stone, but as a space of discipline and discovery. And that’s something I’ll always carry forward.

Do you feel Bangladeshi cinema is finally beginning to embrace stronger, layered female characters?

To be honest, I don’t think we’re there yet—not fully. Female-led films still struggle to make it to the big screen in the way they should. Ours is still a male-dominated industry—and beyond that, a male-dominated society. And I truly believe that unless there’s a shift in the larger societal mindset, meaningful change in cinema will always remain limited.

We’re still not thinking deeply—or broadly—about female narratives. The idea of crafting complex, layered characters for women isn’t prioritized. There’s this tendency to play safe or follow familiar tropes, especially in mainstream cinema.

That said, I do think some interesting efforts are being made—especially on OTT platforms. There, we’re beginning to see stories where women are more than just supporting characters. They have agency, depth, contradictions. In OTT, some space is opening up for women-centric narratives, and I’ve personally been lucky to be a part of that. But when it comes to the big screen, that space still feels extremely limited.

We’re not seeing the kind of bold, female-driven films that other industries—like Bollywood—have dared to make. Take Gangubai Kathiawadi, for example. It’s not just a brilliant character study—it’s also a commercial success. It shows that a woman’s story, told powerfully, can fill theaters.

Sadly, that’s not happening here yet. In Bangladesh, we might get one or two female-protagonist films a year, and even then, they rarely succeed at the box office.

Why? Because success takes more than just a good story. It needs vision, strong execution, and investment. We have powerful stories all around us—about women’s resilience, identity, struggle, joy. But unless those stories are told beautifully and compellingly, audiences won’t be drawn in. And if audiences don’t show up, producers and investors become hesitant to take that chance again.

I personally want to see—and be a part of—films that explore a woman’s journey with all its complexities. I want to go to the cinema and feel something when I watch a female character on screen. And I want others to feel that too.

I think we’re just at the beginning of that shift. Audiences are starting to get curious about alternative narratives, about “off-track” films that don’t follow the usual formula. There’s a slow but visible interest in watching different kinds of stories. So yes, there’s hope. An audience for these films can be built—but it hasn’t fully arrived yet. It’s a journey we’re only now beginning to take.

Would you be interested in producing or directing digital content yourself someday?

To be honest, I don’t think I’ll ever take on the role of a director. I truly believe that direction is an incredibly demanding responsibility—it’s not just about having a creative vision; it’s about leading an entire team, making hundreds of decisions every day, and carrying the weight of the entire project. Having worked closely with directors over the past 15 years, I’ve seen firsthand the kind of dedication, passion, and deep technical knowledge that the role demands.

If I were ever to direct, I would want to do it well. Not just for the sake of saying, “I made a film,” or producing something on my own just to wear the director’s hat. I think that mindset—where anyone can direct without really understanding the craft—can actually do more harm than good to the industry. Direction isn’t something you enter casually. It’s an art form that requires study, mentorship, and experience.

Right now, I don’t feel I have the qualifications to direct. If, at some point, I seriously study filmmaking or take a professional course in direction, then maybe I’d consider it. But as of now, there’s no plan—nor any possibility—of me stepping into that role.

Producing, however, is a different story. That’s something I am interested in. I’ve developed some understanding of what goes into production—the logistics, the budgeting, the creative choices—and I do think that’s a space where I could contribute meaningfully. So yes, I’d definitely consider producing in the future. But direction? That’s a line I don’t see myself crossing unless I’m truly prepared for it.

Is there any skill or hobby you’ve secretly wanted to learn but haven’t had the chance yet?

Yes, quite a few actually. One of them is painting. I absolutely love painting—it’s something that has always drawn me in—but I’ve never formally learned it. And now, with all the responsibilities that come with work and family, I don’t feel I have the time, the space, or, honestly, even the energy to pursue it seriously.

It’s not just about picking up a brush—it takes commitment, patience, and hours of practice. Right now, with so much going on in life, I don’t think I can devote that kind of time to a new hobby, even though the desire is very much there.

Another thing I’d really love to do is learn how to cook different cuisines. I’m very confident when it comes to Bengali food—I can cook almost any Bengali dish with ease. But I also love Indian, Chinese, and Thai food. I would genuinely enjoy learning how to cook those properly. I’ve thought about enrolling in classes, trying out new recipes… but the truth is, I’ve grown a bit lazy (laughs). I have the interest, but I don’t always follow through.

And then there’s table tennis! I’ve always wanted to learn how to play. It seems like such a fun, fast-paced game. But again, like many of my other wishes, it stays a wish. I don’t quite get around to actually doing it.

So yes, there are a lot of little dreams like that—painting, cooking different world cuisines, and learning table tennis. They’re all there in the back of my mind, waiting for their moment. Hopefully, someday, I’ll find the time to pursue at least one of them.

What one fitness ritual do you diligently follow?

I wouldn’t call myself a fitness freak, but I do have a few rituals that are very close to my heart—especially because they help me emotionally as much as they do physically.

To begin with, I’m a very emotional person. I tend to make decisions more with my heart than my head, which isn’t always the wisest thing. Ideally, I believe decisions should be a balance—part heart, part mind—that’s where creativity and clarity both thrive. But in my case, my emotions often lead the way. That makes me vulnerable at times, especially when things don’t go as expected.

That’s where yoga comes in. Yoga has helped me immensely. It’s more than just a physical practice for me—it’s my space to calm down, to breathe, and to center myself. I have a bit of a temper, to be honest. I get angry quickly. The anger doesn’t last long, but when it comes, it consumes me. And what’s worse is that I don’t express it outwardly—I bottle it up. So I end up suffering internally, replaying the emotions and feeling drained.

When I do yoga, I find stillness. It grounds me. It helps me breathe through those emotional storms. It gives me perspective—and a kind of peace that I don’t find anywhere else. So yes, yoga is one ritual I try to follow as regularly as possible.

Another thing I love is walking. When I feel mentally overwhelmed, confused, or just low, I go for a walk in the park. Just one hour of walking—sometimes alone, sometimes with friends—shifts something inside me. It clears the fog. Even if I’m physically tired or feeling unwell, just sitting or strolling in the open air helps reset my mood. Often, by the end of the walk, I know what I need to do. It helps me reconnect with myself.

So, whether it’s yoga or walking, I think movement—gentle, intentional movement—is my go-to way of staying balanced, both mentally and physically.

What’s next for Tama Mirza?

Well, I do have a couple of exciting projects lined up for next year. I’ve already signed on for two films, but unfortunately, I can’t share any details just yet. It’s a decision made by the production houses—they’d prefer to announce it officially when the time is right. What I can say is that both are for the big screen, and I truly hope the audience will welcome me in these new roles.

Right now, I’m in a bit of a preparatory phase—both mentally and physically. Before starting any film, I usually take some time to disconnect from everything. I stay home, watch a lot of movies, and immerse myself in the emotional world of my upcoming character. I reflect a lot during that time—on how I want to appear, what kind of changes I can bring to my performance, and how I can make the character stand out.

This year, the pressure has been lighter. I don’t have any major shoots scheduled for the rest of the year. My next film work is likely to begin in the first week of December, with the actual shoot kicking off in January.

So, for now, these few months—October and November—feel like a breather. I’m just enjoying some time off… eating well, relaxing, spending time with people I love. But once December arrives, I’ll step back into work mode, fully focused, ready to dive deep into character again.

Even a simple walk clears the fog in my head. By the end of it, I often know what I need to do.

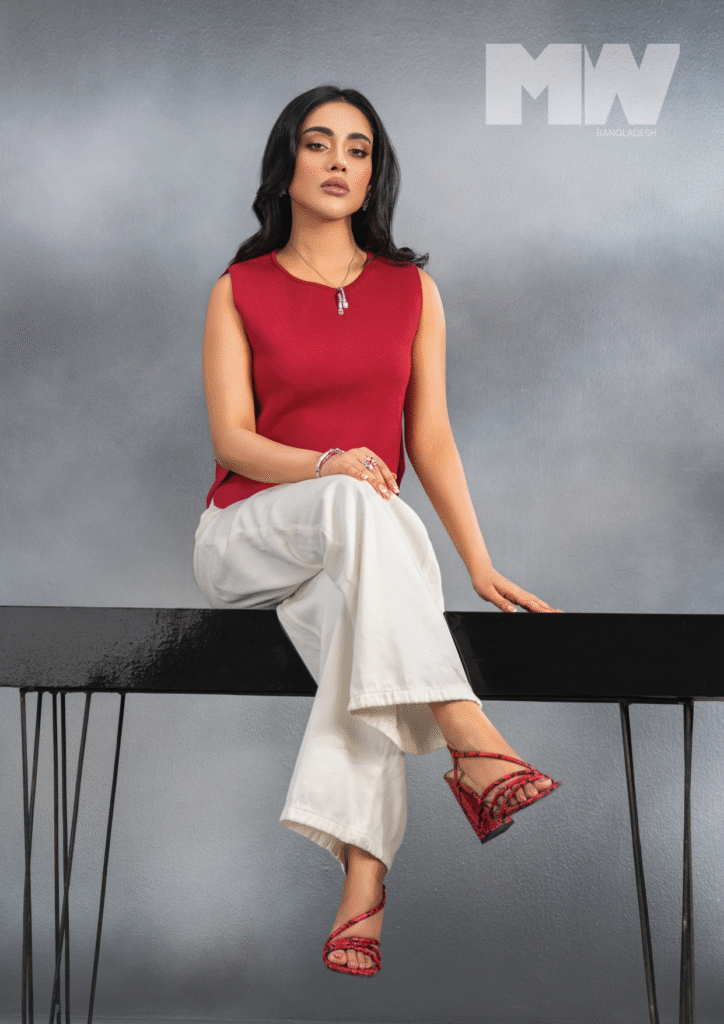

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Rono Zaman

Make-up: Sumon Rahat

Hair Style: Probina Sangma

Assistant Stylist: Arbin Topu

Shoes: Moochie

Jewelry: Jarwa House

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman