By Ayman Anika

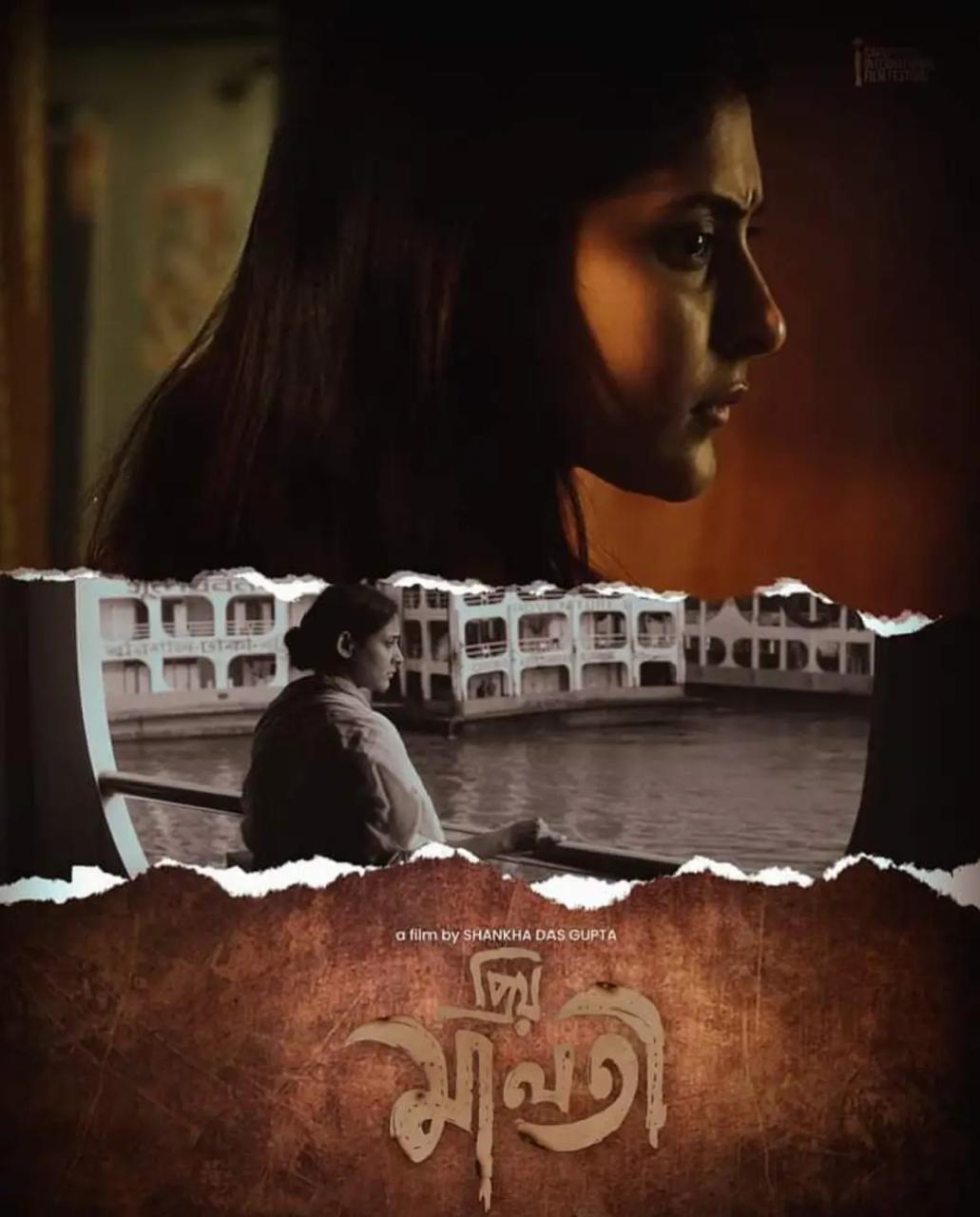

In a world where outrage has an expiration date shorter than a carton of milk, Priyo Maloti (2024) doesn’t whisper for your attention – it screams. Not in hysteria, but in pain. The kind of pain that bubbles beneath the surface of every news headline we scroll past, every tragedy we normalize, every injustice we let die in silence. And yet, ironically, it’s not a film that demands tears. It demands introspection. Director Shankha Dasgupta doesn’t want you to cry – he wants you to feel the sting of complicity.

Plot snapshot: survival as protest

Maloti Rani Das (a soul-baring Mehazabien Chowdhury) is seven months pregnant when the floor collapses under her life – literally and figuratively. Her husband, Palash (played with restrained gravity by Rizvi Rizu Chowdhury), dies in a massive mall explosion where he worked, or so she thought. Turns out, Palash never had an official contract. No paper trail. No evidence he was even employed there.

To make things worse, his body is cremated without a postmortem. No documentation, no compensation. He died doing a job the system won’t admit he ever had.

Maloti is left with a belly full of life and a house full of debt. Her father-in-law, a man carved from opportunism, demands she pay him a handsome loan – just as he once pressured his son. The government promises 20 lakh takas to the families of verified victims. Maloti? She can’t even prove her husband was one of them.

And so begins her quiet war.

In a role that could easily tip into melodrama, Chowdhury plays Maloti with aching restraint. She doesn’t scream, she doesn’t beg for your pity – she simply endures. Her silences are deafening. Her every glance, a loaded monologue. It’s a performance that feels lived-in, like she’s carrying not just her unborn child but the weight of a society that has long stopped caring.

Enter Razzak (the ever-grounded Shahjahan Shamrat), a Muslim man in a Hindu woman’s fight, who risks communal judgment to stand by her. Throughout the film, Shamrat plays the role of a loyal friend with depth. His support isn’t showy. It’s practical. Gentle. Human.

Razzak doesn’t “rescue” Maloti – he simply refuses to let her drown alone after Palash’s death. In a film about systemic indifference, his character reminds us that solidarity, no matter how small, is still revolutionary.

Dasgupta doesn’t frame his film around one calamity but many – the kind that rarely make headlines. Not disasters with dramatic music and camera drones. No. The quiet kind. Institutional decay. Communal tension. Economic violence disguised as policy. The banality of evil in a government office with flickering lights and a broken ceiling fan.

You will not find villains here in black hats. You will find landlords, lawyers, fathers, neighbors. Ordinary people with calcified hearts. No one burns down Maloti’s world on purpose – they just can’t be bothered to stop it from burning.

What Priyo Maloti does brilliantly is reveal how violence doesn’t always come with blood. Sometimes, it comes in the form of a lawyer asking for fees before filing a case. Sometimes, it’s a landlord who wants rent but can’t be bothered if you’re alive. And sometimes it’s in a puja bell that irritates a child because it interrupts his daydreams of ice cream.

These moments, absurd yet devastating, are the film’s beating heart. Dasgupta lays them bear with a quiet, simmering rage. His lens lingers where others would look away – hospital corridors, burnt-out slums, dead-end government offices. Every frame is soaked in institutional cruelty.

The cinematic language of decay

Visually, Priyo Maloti is unflinching. There’s a deliberate drabness to the film’s palette – earth tones drained of warmth, cityscapes caked in soot, homes that echo with silence. The cinematography does not aestheticize poverty or pain. Instead, it captures the texture of the urban neglect of Old Dhaka – gritty, chaotic, and claustrophobic.

As impactful as Priyo Maloti is, it occasionally suffers from its own intensity. The relentless bleakness, while thematically justified, can wear the audience down to the point of numbness –ironically mirroring the very desensitization the film critiques.

Also, supporting characters beyond the central trio often feel more like mouthpieces for ideas than fully realized individuals. The landlord and even Palash’s father – while symbolically powerful – are written with less nuance than the leads. Their one-note cruelty, though effective, misses an opportunity for complexity.

Perhaps one of the more technical shortcomings is pacing. As a two-hour movie, some stretches feel repetitive, especially when the point has already been made. A tighter edit might have made the emotional punches land even harder.

The uncomfortable truth

What Priyo Maloti ultimately asks isn’t whether we see people like Maloti but why we so often choose not to. And perhaps this is the reason why Priyo Maloti travelled all the way to the Cairo International Film Festival. The film represents the reality that we often fail to see.

In a world where empathy is outsourced, where a printed receipt is worth more than a human life, and where love itself is taxed by the hour, this film drops a conch shell in the middle of the noise and asks: Are you listening?

Most won’t be.

But for those who do hear it – really hear it – Priyo Maloti becomes more than cinema. It becomes proof that art can still make us flinch. Still make us feel.

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman