By MWB Desk

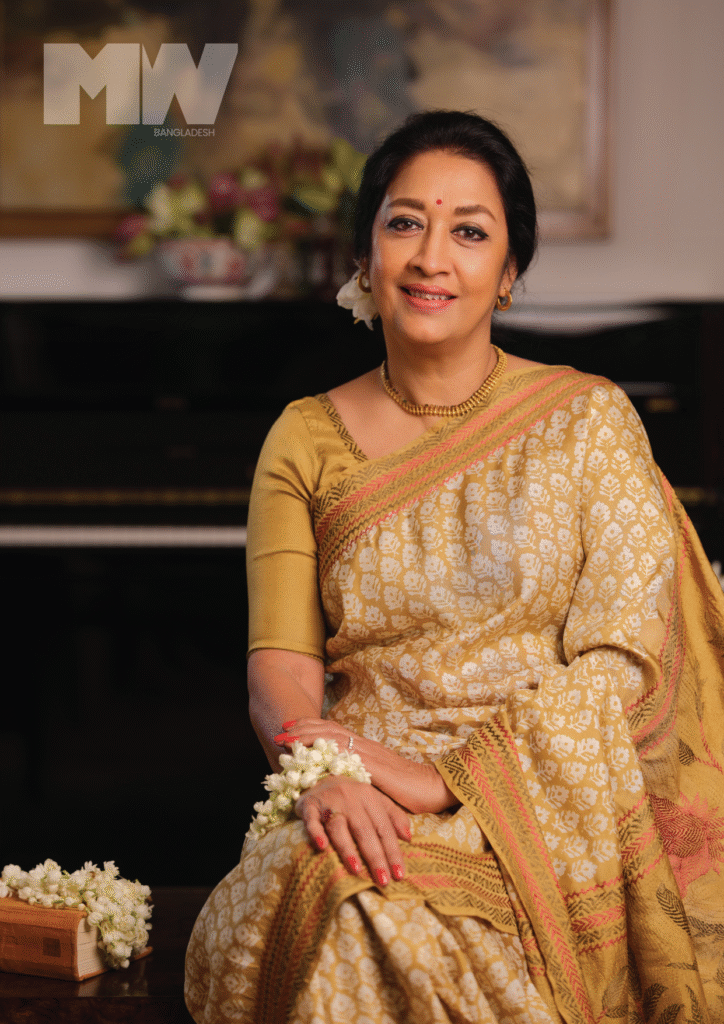

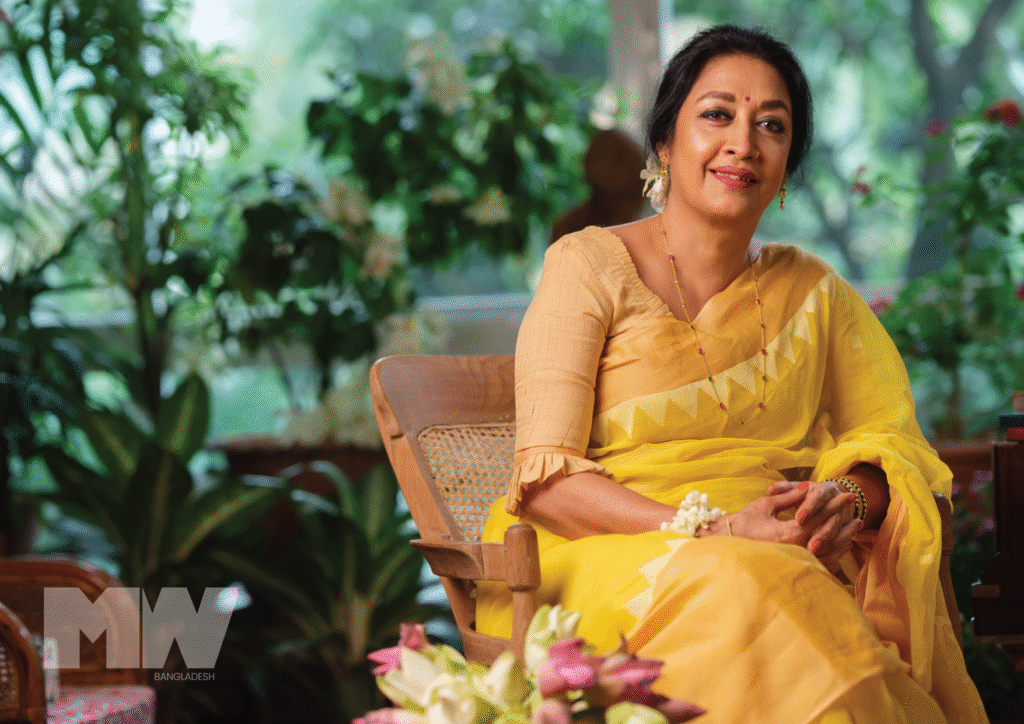

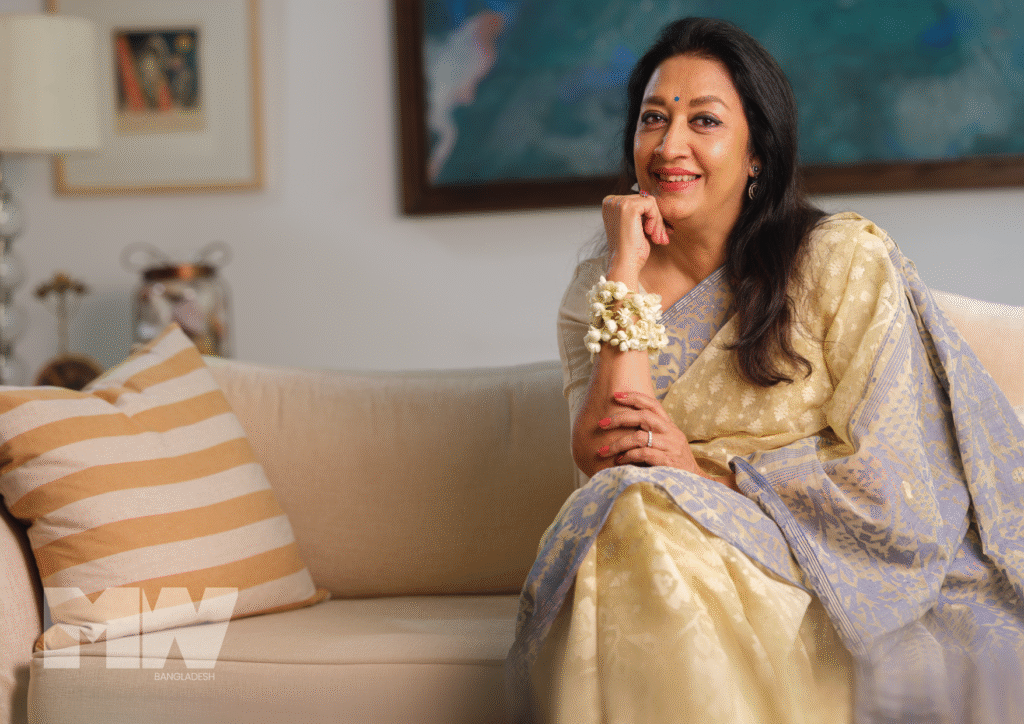

From community halls in London to concert stages in Dhaka, Rahman has carried her music with quiet conviction. Rabindra Sangeet became her emotional anchor while living abroad, and remains at the heart of her artistry. She has released numerous albums under Bengal Foundation, Hindusthan Records, Bhavna Records, and was featured in a 2011 UNESCO release of albums launched in Paris.

Rahman’s voice is unhurried and sincere, her approach rooted in discipline and humility. She rarely seeks the spotlight, believing that true music finds its own listener. Still learning, still listening – she sings not to impress, but to connect.

There’s a kind of music that doesn’t clamor for attention. It lingers instead in corners of childhood, between afternoon shadows and old record players, in the quiet resolve of someone who keeps singing long after the spotlight has turned elsewhere. Shama Rahman’s life in music began not with ambition, but with listening. As a child, the songs that floated from her mother’s record player didn’t teach her notes or scales. They taught her presence. They stayed.

Years later, living abroad and far from everything familiar, those same songs returned to her like an old friend. It was then that she began to understand—not just what music sounded like, but what it meant. Over the decades, Rahman has recorded celebrated albums, performed across continents, and witnessed her voice find a home in hearts both near and far. And yet, she remains someone who still listens more than she speaks, who still studies more than she shows.

With MWB, in a heart-to-heart conversation, the veteran Rabindra Sangeet singer reflects on her quiet beginnings, the long road she has walked, and the journey still unfolding.

You mentioned that your mother’s record player would play in the morning when you were little. Do you think those songs from childhood shaped your taste in music later on?

From my early childhood, I have always said this music was a constant presence in our home. My mother had a record player, and she had a large collection of records and books. Music and reading were her passions. Back then, I didn’t really understand what I was hearing – I was just a little girl. Sometimes I liked the songs, sometimes I didn’t. But I listened to everything.

It wasn’t until I went abroad years later that I realized how much those songs had quietly shaped me. Being far from home – missing my family, my parents, my siblings – the sound of those songs suddenly felt like a path I could walk on. Emotionally, they gave me strength. Even if I didn’t plan to become a singer or even think about music seriously, those melodies from my childhood stayed with me. They would come back to me at difficult times, like a prayer does. That emotional memory, that early exposure – it gave me peace and direction. And when I started teaching Bengali songs to children abroad, I could feel how deeply those early tunes had become part of me.

You took dance lessons in Chittagong before you started singing. Do you think learning dance helped you understand rhythm or body language in music later on?

I was very young when I started learning dance—practically a child. It was my mother who enrolled me in a dance school in Chittagong. I remember being quite shy, and maybe I still am in some ways, but I kept learning. And even though I was too young to fully understand it back then, something about rhythm—about movement—stayed with me. It settled somewhere quietly in my mind.

I truly believe that anything we learn in life, no matter how small, influences us in ways we may not even realize at the time. Learning, after all, has no end. And when it comes to music or any form of the arts—be it playing an instrument like the violin, or learning a classical dance—it shapes the mind. It nurtures something within. So yes, I believe the rhythm I absorbed through dance still lives in my songs. That early training gave me a sense of timing and flow, even if I wasn’t conscious of it at the time.

Dance, to me, is like a form of meditation. It has the same calming effect. It clears the mind, heals the body, and brings you peace. It’s not just exercise—it’s an art form that opens up your inner world. Just like music, painting, architecture, or even pottery—these are all creative expressions that have always drawn me in. I’ve always been deeply moved by art in all its forms, and whenever I feel creatively restless or emotionally overwhelmed, I find myself gravitating toward these outlets. They bring clarity.

So yes, I’m grateful that I got to learn dance. It gave me something that stayed with me—something that perhaps still shapes the way I move through music, through life. It’s all connected.

In many South Asian households, women’s artistic pursuits are often seen as hobbies. How did your parents navigate that expectation – did they see music as a path, a skill, or something else entirely for you?

At the beginning, just like in many South Asian households, my parents treated music as a hobby, and to be honest, I viewed it the same way. Singing was something I loved doing, something that brought me joy, but it was never initially considered a career path or a serious pursuit. My academic subject was English, so naturally the expectation was that I’d do something more ‘secure’ – maybe become an academic, maybe work in education. Those were the conversations I grew up hearing.

But, as I often say, music has always been present in my life. I would sing, and people would respond with warmth. Slowly, as I sang here and there, I began to notice how much others appreciated my voice. I started getting compliments, encouragement, and gradually I realized –this isn’t just a pastime.

This is something I truly love and want to dedicate myself to. And that’s when things shifted. The passion grew stronger, and I became more serious about singing. I made time for it. I began treating it not just as something I enjoyed, but as something I wanted to grow in and pursue professionally.

So, in a way, my parents’ initial approach – introducing music as a hobby – was still significant. If they hadn’t done that, if they hadn’t allowed music into my life in some form, I may never have discovered what it truly meant to me. Teaching music as a hobby might seem casual, but in hindsight, it planted the seed. It provided me with the foundation to build upon.

Later, when I started receiving some recognition, both my parents were supportive. My mother, especially, became a constant pillar of encouragement. She had a deep love for music herself, and seeing me grow in this path made her happy. So, while it wasn’t a planned or structured journey into the arts, it was a deeply organic one, shaped by love, shaped by the gradual realization that something that brings you joy can also become your calling.

And I must say, in our society, pursuing music seriously – especially as a woman – is not always easy. It takes inner conviction, and it also takes outer support. I was fortunate that when the time came, my parents stood beside me. That early encouragement, even if framed as a ‘hobby’, gave me the chance to discover something essential about myself.

You began your formal training under Ustad Fazlul Haque at the age of seven. What do you remember about his teaching style?

Ustad Fazlul Haque was my first guru, and truly, an extraordinary artist. A master. He used to come to our house to teach me, and those early days were very special, even though I didn’t fully realize it at the time. I was young—my mind was a bit restless—so I didn’t always pay close attention. But he was very patient, soft-spoken, and kind. He taught me gently, speaking slowly, helping me ease into classical training.

I still remember the first song he taught me. I didn’t understand the meaning at all at that age, but the melody stayed with me. Gradually, he began teaching me classical music more seriously. And over time, I became more involved, more emotionally connected. It was through him that my journey truly began, and I always remember him for that.

There were these small, beautiful rituals with him. He would come over and say to my aunt, “Let me have a cup of tea first,” and we’d sit on the floor, as was customary then. If there were snacks, he’d be delighted. One day, I remember he praised me to my mother. He said, “She has a lot inside her. If she takes music seriously, she can become a big artist.” I laughed when I heard that—honestly, I didn’t believe it at all. I couldn’t imagine becoming an artist. But he believed in me, even when I didn’t believe in myself. And for that, I remain deeply grateful.

You know, when I was seven, it was a different time. Seven-year-olds today are much sharper, more aware. Back then, we didn’t understand things quite the same way. But I’m thankful that I had a teacher like him in my life, even if for a short time. His presence mattered.

How did your musical training continue after that?

After learning with Ustad Fazlul Haque, my mother enrolled me in Chhayanaut, where I studied under Zahidur Rahim sir. He was also a wonderful teacher—very encouraging. But Chhayanaut was quite far from our home, so I was only able to attend for about two years.

Later, I joined the BulBul Academy of Fine Arts (BAFA), which was in Dhanmondi, much closer to home. There, late Atiqul Islam became my mentor, and I pursued a diploma course that lasted four to five years. At BulBul, I learned a variety of genres—Bhawaiya, Nazrul Sangeet, Bhatiali, and eventually I chose Rabindra Sangeet as my major. But truly, I enjoyed singing all of them.

I had a deep love for Bhatiyali, the earthy river songs, and I connected equally with the poetic intensity of Nazrul. I never limited myself to one form. That period of my life was incredibly fulfilling—it gave me the foundation I still carry today.

While you are widely known for singing Rabindra Sangeet, do you have an interest in other genres as well? What kind of musical experiences do you see yourself exploring in the future?

Yes, of course. I enjoy listening to a wide range of music. I love jazz, especially in the evenings. It has a depth, a kind of emotional weight that really moves me. I listen to a lot of Western music and old classics like The Beatles. Even now, when I have time, I turn to those songs. Their sound, though different, speaks the same universal language: music. It doesn’t need translation. It simply reaches you.

Though Rabindra Sangeet is at the core of my musical identity, I definitely want to explore other forms. I’d love to experiment with originals—songs that are my own, blending the essence of what I’ve learned with newer expressions. That’s my intent. Let’s see where that journey takes me.

And you know, even Rabindranath himself was incredibly modern—he composed on the piano, experimented with different instruments. I think there’s so much room to grow while still honoring tradition.

You’ve also expressed a desire to teach music. Is that something you still hope to do?

Well, I’ve always wanted to teach, to share what I’ve learned over the years. Many people have asked me if I could teach them Rabindra Sangeet or guide them in music, and I think about it often. Teaching is not just about technique—it’s about passing on something that’s lived inside you. That’s very personal.

When I sing, I carry all the voices I’ve heard growing up—singers I admired, the songs that stayed with me. And I hope, someday, others will remember my songs in that same way. That’s the kind of musical legacy I want to leave behind.

To me, a song becomes yours only when it truly lives in you. Every singer brings their own soul into a song, and that’s what makes music so unique. No two performances are ever really the same. The emotional truth, the personal touch—that’s what makes it timeless.

So yes, if I can offer that to someone else, if I can help them discover their voice within a song, I would love to do that.

You’ve spoken of how art – like music, architecture, even pottery – has always drawn you in. Has nature played a similar role in shaping your creative imagination?

For me, nature and creativity are inseparable – deeply intertwined, like breath and rhythm. Just as music has shaped my emotional world, nature has grounded it, expanded it, and constantly inspired it. I truly believe that we are not separate from nature. In truth, we are nature. That realization, I think, has shaped the way I feel, create, and respond to the world around me.

Even the simplest natural experiences can feel magical to me. I find joy in watching a flower bloom or listening to the chirping of birds when I travel a bit outside the city. There’s something extraordinary in these ordinary moments. If you pause to notice them, they can move you deeply. Whether it’s the vibrant green of paddy fields, the smell of wet earth, or the colors of the evening sky – these are not just scenes. They are emotional textures. They awaken something within.

One of the greatest blessings of living in this part of the world is experiencing the beauty of our six distinct seasons. Each season arrives with its own rhythm, its own colors, its own story. From the freshness of spring (Bashonto) to the melancholy grace of the monsoon (Borsha), from the golden harvests of autumn (Shorot) to the stillness of winter (Sheet) – every season brings a new emotional landscape. I find endless inspiration in that. Just observing how nature transforms itself, so patiently, so gracefully, gives me ideas, moods, and melodies. It’s as if nature is composing its own song, and I’m just listening.

In a city like Dhaka, where we are always running from one thing to another, I’ve made it a point to stay close to nature in whatever way I can. I plant trees and wait for the flowers to bloom, and when they do, it feels like a personal blessing. There’s no expectation involved – just a silent, unconditional connection. And I think that’s what true creativity is, too – something you nurture without always expecting something in return.

Nature has taught me to slow down, to observe, to listen. And those are the very things that deepen a musician’s soul as well. Just as the sky paints itself with countless colors at dusk, music too holds layers of emotion that unfold when you give it time. In that sense, I see nature as the first canvas, the first teacher.

I often feel that when we lose touch with nature, we also lose touch with parts of ourselves. Nature has the power to heal – not just the body, but the mind, the heart, the creative spirit. It humbles us and also elevates us. I believe that the more we return to nature, the more we return to ourselves. And from that space, truly meaningful art is born.

So yes, nature is not just an influence in my creative life – it is a constant companion. It helps me feel, reflect, imagine, and hope. Just as a song can bring comfort or beauty to someone else, nature does that for me. And I carry that energy into everything I create.

How do you view the current landscape of music in Bangladesh, especially among younger artists?

I believe change is not only inevitable – it’s necessary. Every generation brings something new, and I think that’s beautiful. Today’s younger artists are experimenting more than ever before. They are blending Western influences with our traditional sounds, creating new expressions, new rhythms. I find that very encouraging, because experimentation keeps the art form alive. It prevents stagnation.

At the same time, we must remember that we come from a culturally rich heritage. Our music, like Bhatiali, Bhawaiya, Nazrul Sangeet, Rabindra Sangeet, are full of depth, emotion, and lyrical beauty. They are not just songs – they are philosophies, stories, and spiritual expressions. Young artists need to stay connected to this wealth. And many of them are doing just that, which gives me hope. I’ve seen young musicians beautifully reviving these classical forms and making them accessible to a new audience.

But to truly flourish, this new generation needs nurturing. They need platforms, mentorship, and more spaces where they can both learn and perform. There are very few structured environments that allow for deep musical training from a young age. Many children, especially in English-medium or international schools, are now learning to perform through school plays or music classes, and that’s wonderful. But beyond school, we as a society need to create more opportunities—more room—for serious musical ‘sadhana’ (dedicated practice).

Singing is not easy. You may be able to sing well for a while, but to hold on to that voice, to evolve with it, you need discipline. You need constant practice. You need to listen to good music, immerse yourself in it. Only then can true creativity emerge from within.

And yes, while there’s a lot of good music being created, there are also some works that feel incomplete or superficial. But I try not to be negative about that. I believe even in those efforts, there is potential. Sometimes young artists don’t have enough guidance, or they lose hope because no one is supporting them. That’s when they get lost or discouraged.

I truly feel for them. They are immensely talented, but talent alone isn’t enough. It needs care, space, and encouragement. That’s why I believe all of us – parents, teachers, audiences – share a responsibility. If we can support them emotionally, artistically, even structurally, they will surely bloom and create something extraordinary.

I hold onto hope. Always. I believe that without hope, there is no movement forward. Every artist has ups and downs – joys, sorrows, failures. That’s life. But if you can stand back up each time and keep going, that’s where the strength lies. And I try to pass on that philosophy through the work that I do. Even today, it’s music, poetry, architecture, even a simple moment in nature that keeps me going.

So, yes, I’m hopeful. Our young musicians have the talent, the vision, and the spirit. They just need the soil to grow in. And I believe we can give them that.

What do you feel is missing from today’s mainstream music scene?

I think what’s missing most from today’s mainstream music is a culture of sadhana – deep, dedicated practice. Singing is not just about performing well once or twice; it’s about nurturing your voice, your emotions, and your understanding over time. That takes discipline, patience, and constant listening. Without that foundation, it’s difficult to sustain quality or bring depth into the music.

Another thing that’s lacking is structured opportunities for learning. From a young age, children need access to music education, not just as extracurricular activities but as part of their growth. While I’ve seen some English-medium schools do this beautifully, offering platforms for performance and creativity, many others don’t have that system. And even fewer institutions exist outside of school where serious classical or folk training is available and respected.

We also need more support systems – not just technical training, but emotional and cultural encouragement. Many young artists feel lost or discouraged because they don’t know where to go, or they don’t find people who believe in their potential. Some of them create beautiful work, but it may never reach the audience it deserves due to a lack of guidance or visibility.

And yes, the conversation around “good” and “bad” music is often subjective. What sounds unfinished to one person may hold promise for someone else. So instead of dismissing these efforts, I believe we need to support and mentor these artists, help them grow. With care and nurturing, I truly believe this generation can create something extraordinary.

I also feel that, as listeners, we have a role to play. We need to listen more mindfully, encourage originality, and celebrate the artists who are rooted in our culture yet unafraid to explore. I’ve seen many young musicians doing beautiful work – reviving folk traditions, experimenting thoughtfully – and that gives me hope. But they must be given room to breathe and the time to mature as artists.

So yes, to enrich our music scene, we need more patience, more platforms, more practice, and above all, more love for the journey of music itself.

In 2011, UNESCO released your albums. That’s a rare honor. What did it feel like to represent your music on such a global platform?

It was a big and precious honor—something I’ll always be grateful for. Having two albums published by UNESCO was not just a personal milestone; it was a recognition of Bangladeshi music on a global stage. I felt proud—not just for myself, but for the heritage I represent.

And the experience of performing at the global ceremony, where Sir Fazle Hasan Abed was also honored—was deeply emotional. To stand there, representing a part of my culture, and to see people respond with such warmth—it was overwhelming in the best way.

When moments like that happen, you feel a deep sense of responsibility, too. It’s not just about your voice anymore—it’s about the stories, the emotions, the history your music carries. That’s powerful. And humbling.

Being invited to surprise Sir Fazle Hasan Abed with a performance at the World Food Prize ceremony must have been a very emotional experience. What went through your mind when you saw his reaction?

It was incredibly emotional. To perform in that setting, and for a man like Sir Fazle Hasan Abed— someone whose work has transformed so many lives — it felt like a small offering, a way to honour his immense legacy. When I saw his reaction, the softness in his eyes, it moved me deeply.

In that moment, it wasn’t about me singing or being on a stage — it was about connection. About gratitude. I was reminded of all the people who’ve quietly shaped my journey, like Ustad Fazlul Haque, who believed in my voice before I did. And now, here I was, years later, offering a song to someone else who had changed the world in his own quiet, steadfast way. That memory stays with me.

You often mention that you’re still learning, even after so many years. How can young musicians develop that same mindset of being open and curious, no matter how far they go?

I truly believe that being a student never ends. Even now, every song teaches me something new. And I think young musicians should hold on to that sense of wonder — that restlessness I had as a child. At seven, I didn’t understand much of what I was being taught. I didn’t even take my first song very seriously. I’d laugh, not knowing the depth of it. But my guru saw something in me — he believed in me before I believed in myself.

That belief matters. And it grows when you allow yourself to remain curious, to ask questions, to embrace the discomfort of not knowing. I’d tell young musicians: never become too sure of what you know. Let every note be an exploration. Be humble enough to listen, even to your own mistakes. That’s where real growth happens.

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Kaushik Iqbal

Assistant Stylist: Arbin Topu

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman