By Sabrina Fatma Ahmad

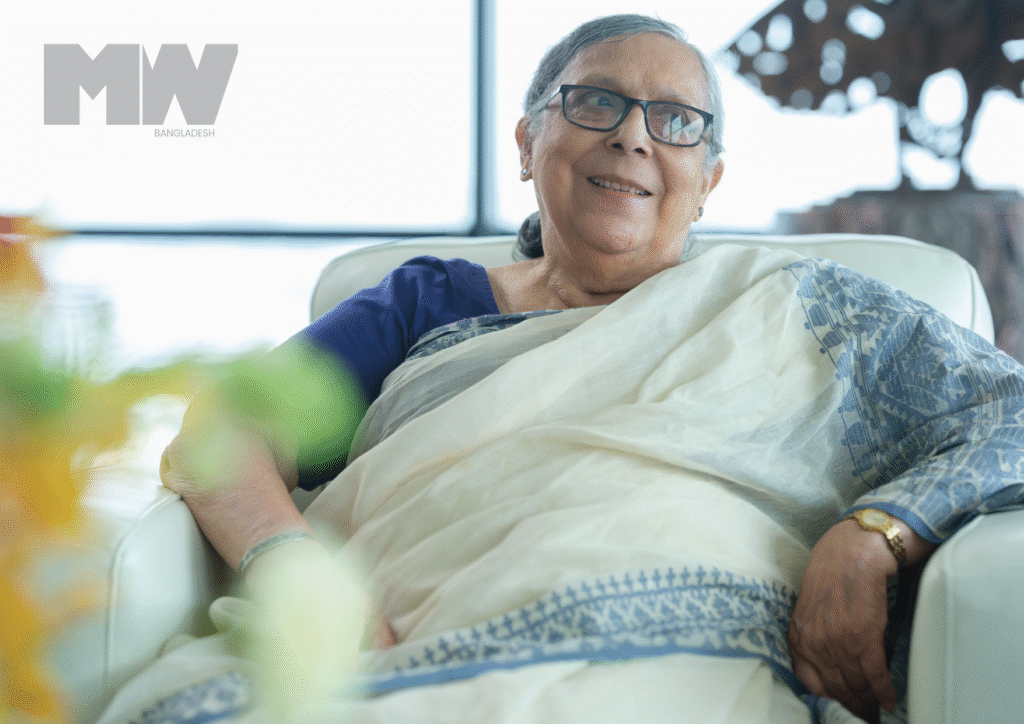

A Punjabi girl is born in Delhi, goes to school in Bengal, marries a Bangladeshi revolutionary, and in her adopted homeland, she builds a literary career so formidable, she ends up winning the country’s second highest civilian honour. While this may sound like an urban fairytale, this is no less than the lived experience of Dr Niaz Zaman: writer, translator, academic, publisher, and winner of the Ekushey Padak.

She has witnessed the Partition, the Liberation War, the rise and fall of several regimes in Bangladesh, and has not only lived through the Covid-19 pandemic and the July Revolution, but has managed to thrive professionally. In a series of short conversations with MW over two weeks, she shares her insights into language, the publishing industry, and more.

Going Dutch and discovering Bangla

The Human Library is a fascinating project conceived by four friends in Copenhagen, Denmark, that has since expanded into a full-blown global organization. Stemming from the idea of people as repositories of stories and experiences, it operates like a library, allowing participants to ‘check out’ a human from a list of vetted and selected individuals, for a conversation about their personal journeys, with the aim of reducing prejudice. Meeting with Dr Niaz Zaman felt less like checking out a single book from a library and more like visiting a museum; rare accounts of our political history preserved with stunning clarity within the fabric of her life story. If I’m mixing up my metaphors, it is because you cannot fit Dr Zaman in a box; she thwarts expectations, challenges stereotypes, and leaves you feeling like you learned more about your own origins than you knew before you met her.

Our first in-person talk takes place outside the café at Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed Park, a shared favourite haunt, where I arrive, apologizing for being late, feeling chastened by the steely glint in her eye which is far more effective than any verbal talking-to. She waves away my offer of a coffee treat in lieu of an opportunity to discuss the phrase ‘going Dutch’ with the barista, thereby proving that you can take the teacher out of the classroom …

We begin with the topic of language. You can’t begin to have a conversation about translating Bangladeshi writing without Dr Niaz Zaman’s name coming up. She’s spent decades making a wide range of Bengali writing more accessible to a wider audience, her work on Kazi Nazrul Islam’s being particularly noteworthy. She initiated the group translation of Nazrul’s novel Bandhon Hara, published as Unfettered. She also translated his novel Mrityukshudha as Love and Death in Krishnanagar and co-translated his Kuhelika as The Revolutionary.Her invaluable contributions landed her the Bangla Academy Award for Translation in 2016. This would be a remarkable achievement for anyone, but more so when one learns that Bangla isn’t her first language. In fact, she didn’t even learn it until well into her college years.

Niaz Zaman née Niaz Ali, was born in 1941 in Delhi. Her father was Punjabi, and her mother, who hailed from Kolkata, was of Persian and Chinese descent. Her father worked for the Indian Civil Service, but in 1947 he opted for a career in Pakistan, settling with his family in what had become East Pakistan after the partitioning of India. “We mostly spoke in Urdu or English at home,” she says, launching into a memory about her father and her grandmother’s love for the cinema, and how Niaz and her siblings were allowed to go watch one ‘good’ movie a month, and these usually were classic Hollywood cinema, although when pressed for a memorable cinema experience, she mentioned Jugnu and Noor Jahan’s singing. “We (the children) had some limited interactions with the service staff, and if I think about it, they must have spoken to us in their language (Bangla), or some broken mix of English or Urdu, perhaps, but I have no recollection at all.” The only interaction she does remember is from 1947, when her father was District Magistrate, Dinajpur, and little Niaz wandered into the staff quarters and the gardener’s wife let her sample panta bhaat. “It is a taste I still remember, and have been trying to replicate.”

Bangla would find its way into her repertoire of languages during her time at Holy Cross College, from where she obtained her Intermediate of Arts (IA) and Bachelor of Arts (BA) degrees. It was during the first meal served there the evening she had reached, that a BA student who had travelled with her taught her the word ‘dhonnobaad’ so that she could thank the cafeteria staff, affectionately addressed as ‘boudis.’ “The first Bangla word I learned was ‘thank you,’ and I think that’s kind of poetic, don’t you agree?” she asks.

“The best advice I’ve ever received

was to mingle with people outside

of my social class. It really

impacted my view on life”

Her hostel supervisor, Sister Joseph Mary, in one of her homilies, talked about the importance of mixing with people outside of one’s social circle. As an English medium student, Niaz had mostly hung out with other English medium students, and she realized that if she were to take Sister Joseph Mary’s words to heart, she would have to converse with the other girls in their language, i.e. Bangla. This prompted her to ask a friend to teach her the Bangla alphabet so that she could better communicate in the language. This informal introduction to the language would one day blossom into an impressive career in translation.

When the personal becomes political

Throughout the 50s and 60s was a time of personal growth for Niaz Zaman. At Holy Cross, aside from her academic pursuits, she was involved with theatre, stepping into the shoes of various characters, a skill that would prove useful in her literary career. “While I wouldn’t play the role today, because of the anti-feminist bent of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, I rather enjoyed playing the role of Petruchio,” she remembers fondly, adding other male roles such as Sir Toby Belch from Twelfth Night, the titular role in King Lear, and King Creon from Antigone by Sophocles as being enjoyable experiences.

Although she was initially considering studying history, she was inspired by her brother Reza Ali, who was in the honors program at Dhaka University at the time, to join the English Department instead. During her university years, she enjoyed riding a bike to classes, reading plays on the radio, and acting on stage – in addition to her studies. In 1962, the MA Preliminary exams were postponed following student protests. A senior friend, who was taking her law exams, requested her to substitute for her at Viqarunnessa Noon School. She took up the offer and taught at her old school for three months. After obtaining her MA in English Literature in 1963, she began teaching at Holy Cross College. She got married to Kazi Siddiquzaman in 1964, and continued teaching at Holy Cross until 1969, when her husband was transferred to Chittagong, and in following him there, an opportunity to teach at Chittagong University opened up for her. While in Chittagong, she strengthened her knowledge of Bangla by reading Tagore’s short stories.

As a non-Bengali from a fairly privileged family, with a career in academia, Niaz Zaman would be sheltered from a lot of the wider goings-on in the region, but as tension between the two provinces of what was then Pakistan began to escalate, the politics became very personal.

In an autobiographical essay called ‘The Journey Home’ in the Daily Star, about her experiences of 1971, she recounts the story of how her family narrowly evaded capture or worse in Karatia, where they had been sheltering. She talks about how she managed to flee to Karachi and then Lahore with her children, of how her sons, traumatized by their experiences, would hide under the table every time they heard loud noises. She talks about the confusion, and how other relatives without access to reliable information coming out of Bangladesh, had their own fears about the war, and how this fed into her dilemma about rejoining her husband in Dhaka. What stands out in that essay is that complicated fear:

“My mother had pleaded with me to stay back in Lahore. If not for myself, for the boys. When she had embraced me at the airport, she had tears in her eyes, but mine, anxious as I was to board the plane, had been dry. If war broke out, when would I see her or my father, or Nani Bibi or my sisters again? The tears came now but there was no time to weep.

“The seat belt sign came on. I woke up the boys, fastened their seatbelts. Had we reached Dacca, Zarre asked. Not yet, I said, we still had a few more hours to go. But we would be there, soon, InshaAllah.

“As we disembarked from the plane to wait at Karachi Airport for the flight to Dacca, I wondered what Siddique had really meant when he asked me to remain in Lahore. That he no longer loved me? Or that he wanted the boys and me to be safe?”

Her personal experiences were testament to the fact that while politicians and their military played their war games, real lives were being impacted. The intricacies of interpersonal connections that went beyond nationality were now threatened, and with atrocities being committed on all sides, things weren’t as black and white as they are sometimes portrayed, and it is perhaps this knowledge that prompted her to narrate her truth through her writing. Her study of Partition novels, titled A Divided Legacy: The Partition in Selected Novels of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, would go on to receive the National Archives Award as well as an award from the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. She edited several short story anthologies including The Escape and Other Stories of 1947 and 1971 and After. She is also co-editor of Fault Lines: Stories of 1971.

“Why did I come back? I suppose

it was because I had thrown in

my lot with Bangladesh. I was

aware of what they [the Pakistani military] done here,

and it was insupportable”

Life lessons and female rage

In 1972, Niaz Zaman finally joined the English Department at Dhaka University, where she continued to teach until her retirement in 2013. During the political turmoil in the late 1970s, she completed a second MA from the American University in Washington DC. From 1981 to 1983, she served as Educational Attaché at the Bangladesh Embassy in Washington DC, and before she returned to Bangladesh, she completed her PhD from the George Washington University in 1987.

“Professor Niaz Zaman turned her table fan towards me, and dived back into writing. I realized that the two droplets of sweat that fell from my forehead onto my exam paper did not escape her notice,” writes Md Saiful Islam, an academic based in Toronto. “While she kept writing in the suffocating heat, the ceiling fan covered the rest of the cohort of graduating students. In that tutorial course, I learned more about doing research than I had in the previous four years at the University of Dhaka. Ever so enthusiastic, ever so alert, ever so caring, always teaching, always writing, always educating her students and community, and always giving, sharing, yes, that’s my teacher Professor Zaman. My debt to my teacher is so immense that it is not easy to figure where to begin and how to draw an end. In 2020 while writing my MA Thesis in the University of Guelph, Canada, A Divided Legacy (2001) had been my intellectual wherewithal – the book that I went back to frequently. I made it to my second Master’s (thesis) program and received some funding in Canada because of the references Professor Zaman wrote at a short notice request. Not just me, countless students got into international programs with her support. Countless students had their professional résumés reviewed by Professor Zaman. Many got employment in universities, in media, in publishing houses because of her. I wish I had enough space here to talk about the way I learned to become a translator through the workshops I took with Professor Zaman. I wish I could pen here about the support I received from Professor Zaman for my creative endeavors.”

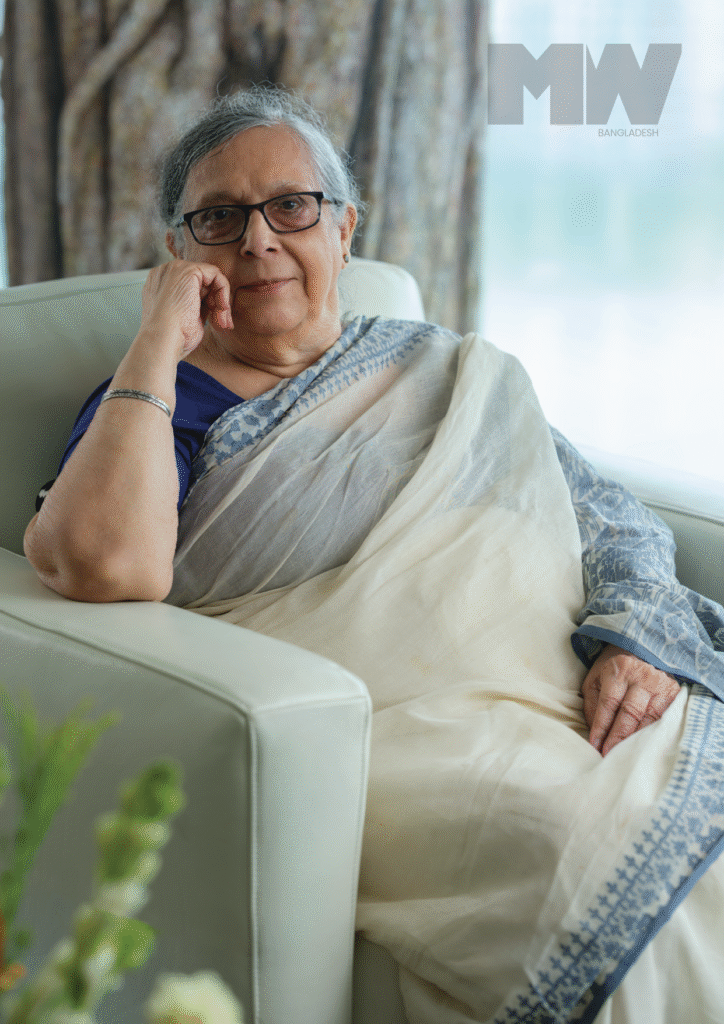

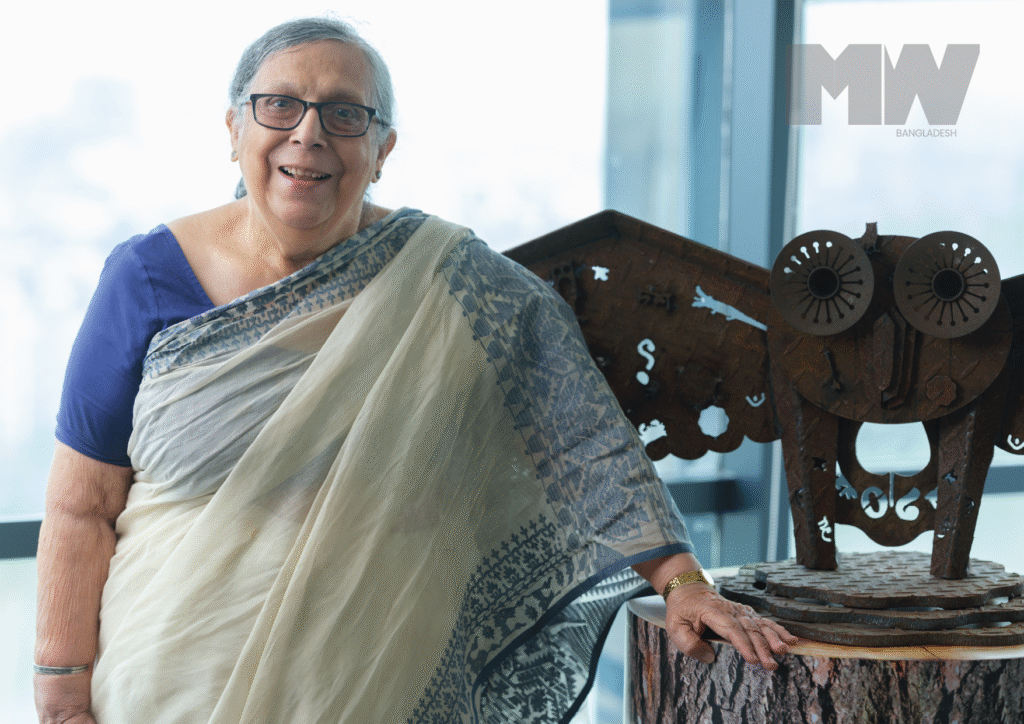

My second in-person conversation with Dr Niaz Zaman takes place at the Samson Centre, where our photoshoot for the issue’s cover is underway. I ask her if she has a teaching philosophy. “When I was starting out, I was determined to know everything about the course I was teaching, so that I had the upper hand over my students. I would meticulously do my research. After a few years of this, I realized that in the classroom, there was only one of me versus however many students there were in the class. I would never know more than all of them combined. So, I don’t know about my philosophy of teaching, but my approach since then has been to accept that, collectively, the classroom has more knowledge than the teacher, so I can always learn more from them.”

“My teaching philosophy? I will never

know more than all the students in my

classroom, so it is futile to try”

We discuss her side hustles and the intersection in our career paths, where in 2006, Dr Zaman joined the Department of English and Modern Languages at my alma mater Independent University Bangladesh (IUB) as an adviser. She was also a consulting editor, Arts and Humanities, for Banglapedia, the editor of the Bangladesh Journal of American Studies, and the literary editor of New Age. We talk about panel discussions and literary festivals, and compare notes on book reviews – agreeing that Tahmima Anam should have credited Jahanara Imam for much of the material that was used for her debut novel The Golden Age. Invariably, the conversation reverts to the subject of writing and translations. I cannot help but note that some of her more significant pivots came about as an angry reaction to some perceived patriarchal slight. One example would be her foray into editing short story anthologies.

“I was in India on a medical trip for my husband, who was not well. In those days, I always wore a saree. And if you know, there’s a difference between the way East Bengalis wear their sarees and the way West Bengalis do – West Bengali women walk everywhere, so their sarees are shorter, or worn higher … I was on my way to get some tea for my husband, when a man, noticing the way I wore my saree asked me, ‘How is Tasleema Nasreen?’ I was furious. I thought to myself I don’t think you’ve read anything by her. All you know about her are her controversies.’ To him, I said she [Taslima Nasreen] was fine, but in that that moment, I decided that I was going to write, I was going to collect, edit, and translate short stories to show that there are other writers from Bangladesh, worth reading about.” Initially, the project was to be exclusively women’s writing, because Dr Zaman felt that women writers lacked representation. An encounter with Professor Syed Ali Ahsan at an evening at the Ganabhaban convinced her to include male authors to make her prestigious UPL publication more representative. She would go on to compile, edit, publish, and contribute to several short story anthologies, including the formidable brick that is When the Mango Tree Blossomed.

Another moment of frustration came after reviews of some of the short story compilations. Some reviewers criticized Dr Zaman’s inclusion of The Customer by Farida Hossain, who hadn’t yet won the Ekushey Padak, as lacking in substance. “Men cannot appreciate women’s stories. Women often approach larger themes through subtle details and settings. Men are always looking for ‘important’ topics to talk about,” she grouses. After facing similar kinds of pushback when trying to find publishers for women’s writings, an exasperated Dr Niaz Zaman decided to take matters into her own hands and start her own publishing company. She hoped to start a feminist press with Dr Firdous Azim. They named it Rachana. Together they published Bhinno Chokhe and Different Perspectives – the outcome of a women’s writing workshop at Goethe Institut, Dhaka. An expanded collection, with just short stories, was published by Saqi Books, London. Rachana and writers.ink took permission to bring out a Bangladeshi edition, which has now gone through several reprints. The plan to expand Rachana did not go ahead, but when she was unable to find a publisher for a Bangladeshi edition of Syed Waliullah’s Tree Without Roots, she started writers.ink, to publish writings in English and English translation. Although writers.ink began its journey by publishing a male author, it actively promotes women’s writings by publishing anthologies and single-author books by women. And Dr Zaman doubled down on those ‘little details that men don’t notice’ as the author of The Art of Kantha Embroidery and co-author of Strong Backs, Magic Fingers: Traditions of Backstrap Weaving in Bangladesh.

“I am Niaz ma’am’s former student from Dhaka University,” writes Sabreena Ahmed, an Associate Professor from the Department of English and Humanities at Brac University. “I am grateful to her for inspiring me to translate Bengali short stories to English. Her meticulous editing taught me how to translate well. Professor Zaman maintains the ethics of editing and sends the remuneration to the translators on time, a practice that is often absent among many editors. She treats all her students without any bias and patiently answers questions in class whether the student is a topper or a backbencher.”

Despite these moves, which would be considered revolutionary in some circles, despite her lifelong efforts to create space for women’s expression, which also includes her book club (for all genders) The Reading Circle, or her literary collective Gantha, Dr Niaz Zaman isn’t a card-carrying feminist. In fact, she prefers not to be boxed up or labelled in any way, choosing to walk her own path.

I ask her how she feels after having won the Ekushey Padak. Her response is a little more mellowed out than her reaction in 2013 when she won the Ananya Prize, where she had initially even considered refusing the prize before eventually capitulating when she realized the huge gender gap between the male and female recipients of the award. The tenor of her response remains the same, however. “I am not entirely comfortable with the attention that comes with any kind of award,” she confides. “One of the advantages of having a masculine-sounding name like Niaz Zaman is that people have often mistaken me for a man during our correspondences, and this bit of ambiguity gives me a kind of cover, which gives me the freedom to continue working as I have. But when you get a big award, and there are pictures of you, and people make the connection, it brings a greater level of scrutiny into your work. I’ve already gotten into trouble for some of my opinions,” she finishes with a chuckle.

As we break for lunch, I ask her about the recent furore about AI and its potential to disrupt education and the creative industries. She waves away my concerns by telling me that people are still smarter and more creative than AI, and that if they educate themselves with how to use it properly, they could work with the tech instead of against it. I contemplate the resilience of this woman who has seen the fall of an empire, the creation of three distinct nations, and the rise and fall of several regimes. If there’s someone who is inured to paradigm shifts, it would be our cover star. Any final words of advice? I ask her. “Do what you enjoy,” she responds without hesitation. “If you enjoy what you’re doing, you’re likelier to take it far.”

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Kaushik Iqbal

Assistant Stylist: Arbin Topu

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman