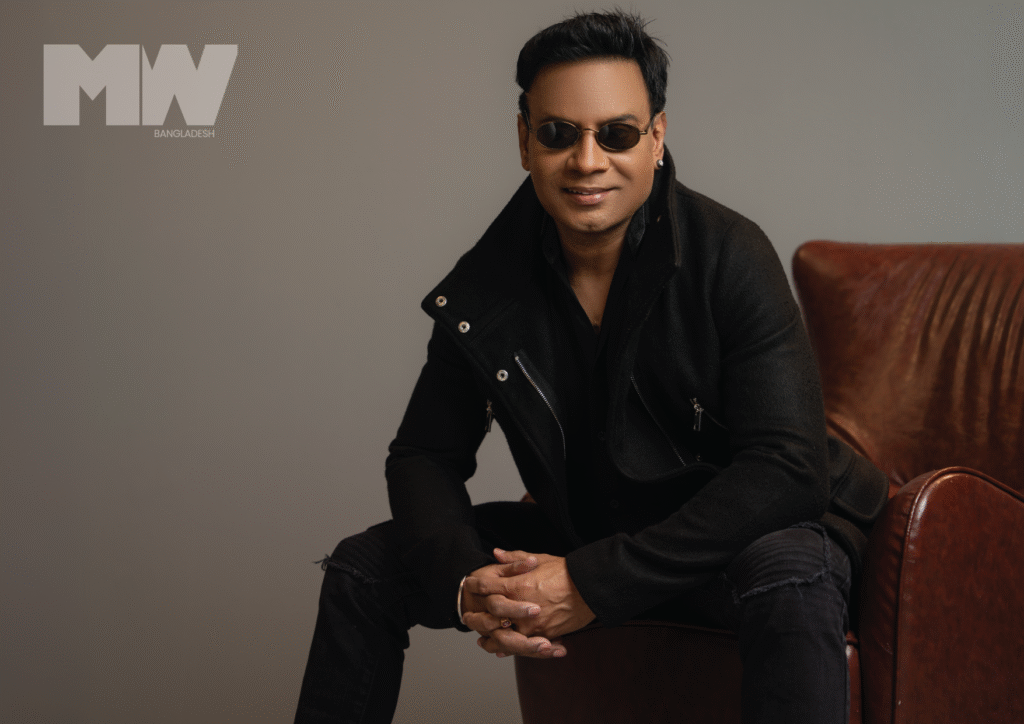

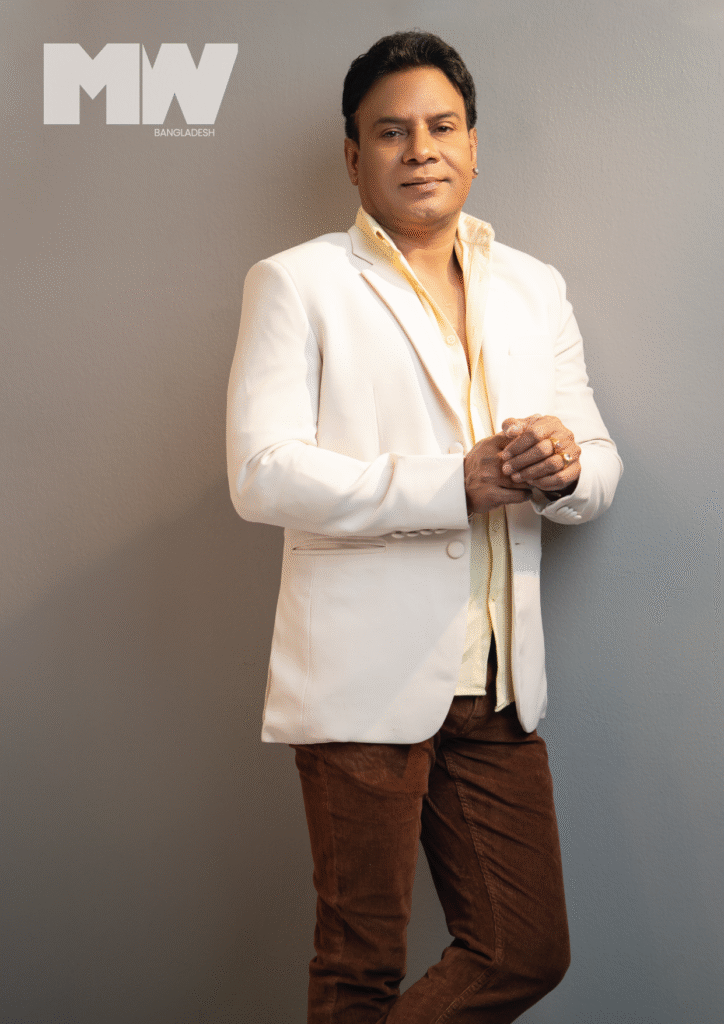

Conversations with Anisul Islam Hero

By Ayman Anika

“Movement is language, and I’ve spent my life trying to speak it with clarity” – this is how Anisul Islam Hero describes his journey in dance.

For someone who began dancing at 16 – an age considered “too late” in most classical traditions – the renowned dancer has never followed the typical script. Instead, he rewrote it. Trained in Bharatanatyam under the legendary Leela Samson, with further studies in ballet, modern, and contemporary dance in Germany and Austria, Hero is not just a dancer – he’s a cross-cultural story-teller who’s built bridges through choreography.

In 1994, he founded Srishti Cultural Centre, one of Bangladesh’s few institutions devoted to serious dance training and performance. And this year, he collaborated with MW Magazine Bangladesh for Bengal in Motion.

The veteran dancer opens up about his journey so far – how movement became his medium, what dance in Bangladesh urgently needs, and why, even after 30 years, he still sees his most meaningful work ahead of him.

Let’s start at the beginning – you didn’t start dancing as a child. What drew you into it, and what made you stay?

Yes, that’s right – I didn’t start dancing as a child. I began quite late, around 18, not even 16 as many assume. It happened when I had just started my honors studies after graduating from Notre Dame College, Dhaka. Around that time, I enrolled at the Bulbul Academy of Fine Arts.

I did have doubts early on. I wasn’t confident – I hadn’t learned to dance as a child, and when I joined Bulbul Academy, I was placed directly in the adult first-year class. The others there were mostly younger than me, but far more skilled. That created a sense of hesitation. I struggled, especially during the foundational exercise classes. I felt lost and out of place, like I was stumbling in deep water without knowing how to swim. There were moments when I was drenched in sweat and completely disoriented, unsure if I’d be able to continue. But slowly, with the support of friends and teachers, I began to find my rhythm. I started to catch up, bit by bit.

What actually motivated me to start dancing is a story of friendship. Two of my close friends –Sohel Rahman and Anup Kumar Das – were both involved in dance.

Watching them sparked something in me. When we all graduated from college, we wondered how we could stay connected. Anup was joining the Bulbul Academy, and Sohel suggested I join there as well. To maintain that bond of friendship, I enrolled – and that’s how my journey with dance began.

“What actually motivated me to start dancing is a story of friendship.

But the one person who truly became my pillar was my guru, Leela Samson“

Who supported you the most throughout your journey?

Throughout my journey, I didn’t have the kind of push from my family that some artists might speak of, but I also didn’t face resistance. My father had passed away, and while my mother never explicitly stopped me from dancing, she was understandably worried. As the youngest in the family, she felt a bit insecure about my future. Every time I came home on vacation, she would get emotional and suggest that I settle down with a job instead of continuing on an uncertain path. Her concern came from a place of love, not discouragement.

Still, my siblings stood by me – they didn’t object to my choices, and in their own way, they supported me. And eventually, I developed a kind of inner determination. I had formed the habit of learning, of seeking more. That’s what drove me to go back to India, despite the uncertainties.

The one person who truly became my pillar was my guru, Leela Samson. She supported me not just as a teacher, but like family. She gave me all the love and guidance I needed, filling in the emotional gaps I felt from losing my father. She even called me her son – and still does. Her way of teaching, her affection, and her faith in me kept me going.

It was through her that I not only stayed motivated but also earned a scholarship and spent five deeply formative years in India. Her love and mentorship were the most powerful anchors in my journey.

You’ve trained in so many styles – Bharatanatyam, ballet, and modern techniques. Can you share some of your cherished memories?

One of the most cherished chapters of my dance journey began when I received a scholarship to study in Europe – at a time when contemporary or modern dance wasn’t really practiced or even known in Bangladesh. I remember the very first workshop I taught at the German Cultural Centre in Dhaka. The director at the time noticed that I, along with a few others like me, was introducing something different.

She invited me for a conversation and asked, “What are you thinking about dance?” I told her honestly that I was still figuring things out. She then asked if I’d be willing to pursue ballet or modern dance abroad if given the chance. I said yes, of course – and that conversation planted the seed.

Eventually, he helped secure my scholarship to Germany, and soon after, Ramendu Majumder arranged another scholarship for a summer ballet seminar in Austria, in a small mountain resort town called Wolsegg. That’s where my formal ballet journey began.

I’ll never forget how my ballet teacher reacted after just a week of classes. He asked, “You’ve never learned ballet before?” I said no – this was my very first ballet class. He was stunned. Even a Russian pianist who was there asked me the same after watching my progress. That moment gave me immense confidence. I performed there, not just in ballet but also Bharatnatyam.

One unforgettable memory was when a German professor asked to see my Bharatnatyam rehearsal. He posted it publicly, and I suddenly found myself performing a full one-and-a-half-hour solo in front of 150–200 participants. To my surprise, I received a standing ovation and was later asked to perform the Tillana as the opening act of the final show. That night, I walked into the dining hall to applause, flowers, and champagne – it was overwhelming.

You once said that classical training is the backbone of any good dancer. Why do you think that’s still important today?

Yes, I firmly believe that classical training is the backbone of any good dancer, even today. I’ve seen and experienced many styles – modern, contemporary, ballet – but it’s the classical foundation that truly sharpens a dancer’s craft. When I lived in Delhi, I had the rare privilege of watching some of the greatest gurus perform, and that shaped my understanding of what true mastery looks like.

Take Pandit Birju Maharaj, for example – his choreography was nothing short of magic. Such grace, such control. Despite his small frame, the way he took command of the stage was mesmerizing. He didn’t just perform; he lived each movement. The very same compositions we would rehearse with such effort, he would render with effortless elegance. That’s the power of deep-rooted classical training – it gives you command over body, rhythm, and emotion in ways that are hard to achieve otherwise.

I know you’ve spoken before about how dancers are often sidelined in mainstream media. Has that changed at all in recent years?

Unfortunately, no – nothing has really changed. Dancers are still sidelined in mainstream media, just as they were before. In the past, it was mostly corporate shows or entertainment channels that overlooked dancers in favor of more commercially “marketable” performers. But now, even BTV – our national television – has started doing the same.

Let me be clear – I’m not belittling anyone. Models and actors are artists in their own right. But would you cast a dancer in a television drama without acting experience? Probably not. So why place someone without proper dance training in a performance role, sidelining those who have dedicated their entire lives to this art?

It’s disheartening when trained dancers – who’ve been learning since childhood – are told, “These girls will dance behind you.” That kind of treatment strips away their dignity. Senior performers are especially reluctant to accept such roles, and rightly so. This creates a dilemma for choreographers and teachers like us. How do we explain this to our students who’ve worked so hard, only to be reduced to background decoration?

Are digital platforms – like Instagram or YouTube – helping dancers in Bangladesh get more visibility?

Yes, digital platforms like Instagram and YouTube have certainly made it easier for dancers in Bangladesh to gain visibility, but that visibility is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, social media has democratized exposure. Anyone can share their work, and anyone, anywhere, can watch it. Good performances now have the potential to reach wider audiences without waiting for traditional gatekeepers. But at the same time, this open access means that everything is being seen – the good, the bad, and the utterly absurd.

The problem is, our lens has shifted. Once, people judged art by its quality – how well someone performed, how rigorously they trained. Now, it’s about how many views a video gets. That number has become the benchmark of success, not the depth or discipline of the performance itself. And the tragedy is, in this race for metrics, serious, well-trained dancers often get overlooked – because their work may not be sensational or meme-worthy enough to go viral.

So yes, platforms are giving us more reach – but they’re also redefining what we consider “popular” or “good,” often in ways that don’t serve the art itself. The challenge now is to find a way to use these platforms without compromising the integrity of the craft.

You’ve been running Srishti Cultural Centre for decades now. What are you most proud of from that journey?

What I’m most proud of from my journey with Srishti Cultural Centre is not a particular award or accolade – it’s the people and the lives I’ve had the privilege to touch through my work. Over the decades, I’ve taught thousands of students: children from slums, children with disabilities, members of the hijra community, and countless others from all backgrounds.

Many of them went on to become celebrities; many were foreign students – possibly more than any other Bangladeshi dancer has taught. My intention has always been to share whatever I’ve learned with as many people as possible, because at the end of the day, I won’t take any of this knowledge with me. This is what I’ve tried to do through Srishti – not just in Dhaka, but across Bangladesh.

What stays with me are not just the performances or workshops, but the moments of genuine connection and respect. Once, at Dhaka airport, a woman in a Saudi Airlines uniform came up to me, touched my feet, and introduced herself in Bangla: “Sir, I used to be your student.” That moment humbled me.

And there’s something else I want you to include – something people often overlook. There’s a perception in our society that artists lack religious values or discipline. That’s simply not true. I still practice my faith. I fast during Ramadan. I try to perform all five daily prayers. I’ve performed Umrah with my mother, and I hope to perform Hajj soon.

There have been times when I refused to shoot during Tarawih prayers. Productions would adjust the schedule for me. I remember once at BTV, I took my makeup and prayer rug, performed the full Tarawih there, and then went to the shooting floor. Just because I dance doesn’t mean I’ve strayed from God. Many people don’t know this about artists – they assume we’ve abandoned our values. But that’s not the case.

“What I’m most proud of from my journey with Srishti Cultural Centre is not

a particular award or accolade—it’s the people and the lives

I’ve had the privilege to touch through my work”

You recently curated Bengal in Motion with MW Magazine, celebrating Tagore through dance. What was the inspiration behind how you curated the event?

The inspiration behind Bengal in Motion came from a mix of personal history, artistic vision, and a shared desire to celebrate culture meaningfully. Rumana Chowdhury, the editor of MW Magazine, has been a long-time acquaintance – she once attended my classes, and over the years we’ve traveled together for performances, including in Sri Lanka and Bangkok. For a while, she had been encouraging me to collaborate on something artistic.

Last year, we attempted our first event together, but I had just undergone bypass surgery, so I couldn’t perform. I only curated and gave a speech. That experience, though, became a valuable lesson – it helped us understand what it takes to organize an event of this scale. We experimented with different dance forms then. This year, when we sat down to plan the second edition, Rumana suggested we center it around Rabindranath Tagore. I agreed immediately.

From there, the concept evolved. After several meetings, we decided to present a range of classical dance forms – Kathak, Manipuri, Odissi, Bharatanatyam – each interpreting Tagore’s work in a unique way. We also included dance dramas to reflect the narrative richness of his compositions. We were fortunate that Square Group agreed to sponsor us again; support for dance events is rare these days, so their continued patronage means a lot.

What truly made this event special, though, was the audience. A good audience changes everything. As performers, we feed off their energy. When the room is engaged and respectful, the performance becomes a dialogue. We’ve received so much positive feedback – people telling us how meaningful and enjoyable the event was. And that reaffirms what we set out to do: not just entertain, but elevate through art.

We never aimed to be entertainers. There’s a difference between entertainment and artistry. Our intention was to present something rooted in cultural and aesthetic value. And in that sense, I believe the event was a success.

That said, as an artist, there’s always a lingering feeling of “What if?” I always feel something could have been done better. That sense of incompleteness never leaves you. It’s part of being an artist – you’re always striving, always evolving.

But I also recognize how far I’ve come. I’ve performed in diplomatic missions across the world, representing Bangladesh. Whether it’s the Foreign Service Academy or international events—even one involving the President of the United States—these are opportunities that came because people trusted me to represent the country with dignity.

If you had to imagine the future of Bangladeshi dance, say 20 years from now, what do you hope it looks like?

If I imagine the future of Bangladeshi dance 20 years from now, I genuinely believe there will be a return to pure, classical dance. Right now, the scene is very unstable – anyone can dance, post it on social media, and become momentarily popular. But how many are truly trained? How many are invited abroad solely for their dance? Very few.

I always say this: people like us, who progress step by step, last longer. We’ve built something by training students – many of whom have become excellent artists. That gives me a deep sense of satisfaction. Unlike those who come and go, we’ve created a legacy.

I think when people grow tired of the current chaos – of random movements, weak lyrics, and lack of discipline – they’ll return to the roots. History shows that after every period of cultural turmoil, a renaissance of good things follows.

I’ve seen hope in unlikely places. At competitions like Education Week or Shishu Academy, classical dance and music still have value. In rural areas, students often surprise me with how well they perform. If I could give more than 100 marks, I would. They practice sincerely, often more than city kids, who struggle with school pressure and traffic.

“Dancers are talented in more ways than people realize. And I have full faith that

the future of Bangladeshi dance will be brighter,

more rooted, and deeply respected“

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Sagor Himu

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman