By MWB Desk

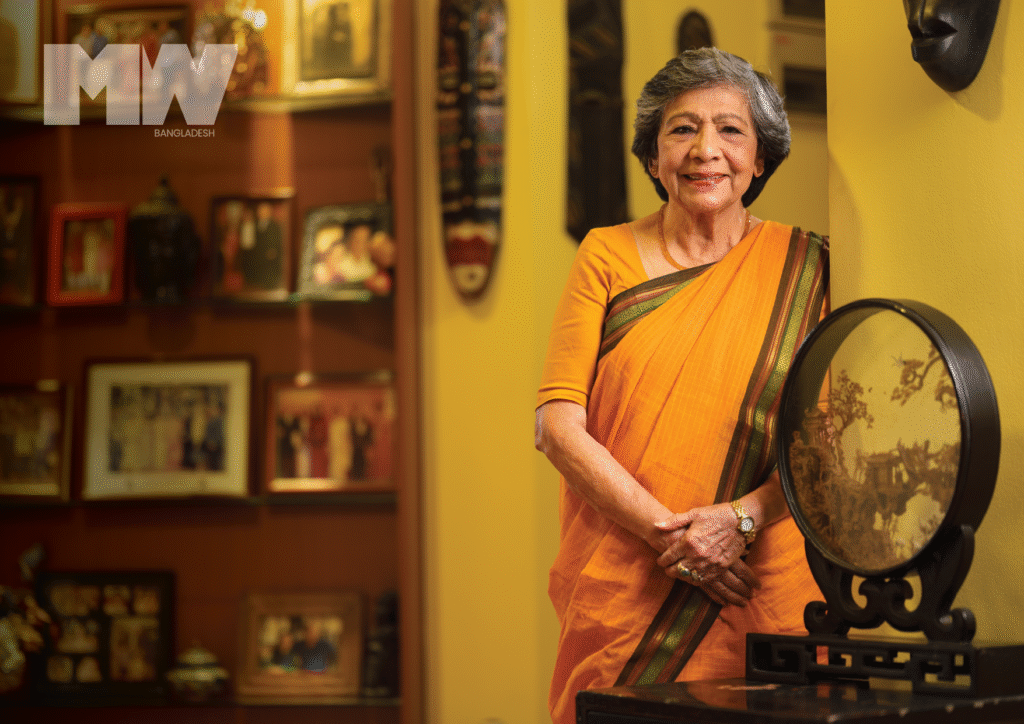

You don’t walk into a room with Geeteara Safiya Choudhury. You enter a chapter of history.

Not just because she has lived through some of Bangladesh’s most defining moments—Liberation, reconstruction, revolution, reform—but because she has refused to merely observe them from the sidelines. With each turning point in the nation’s story, she has carved a path for herself where few women dared to walk, let alone lead. And yet, there she stood: calm but uncompromising, elegant but unshakably firm—armed with nothing but instinct, integrity, and a fire for truth.

You might first notice the soft drape of her saree, the quiet authority in her voice, the timelessness of her presence. But beneath that graceful exterior is a woman who has scaled bamboo ladders in the dark, faced down doubters in male-dominated boardrooms, and stared into the bureaucracy of a government with the same resolve she once brought to lipstick campaigns and fertilizer rebrands.

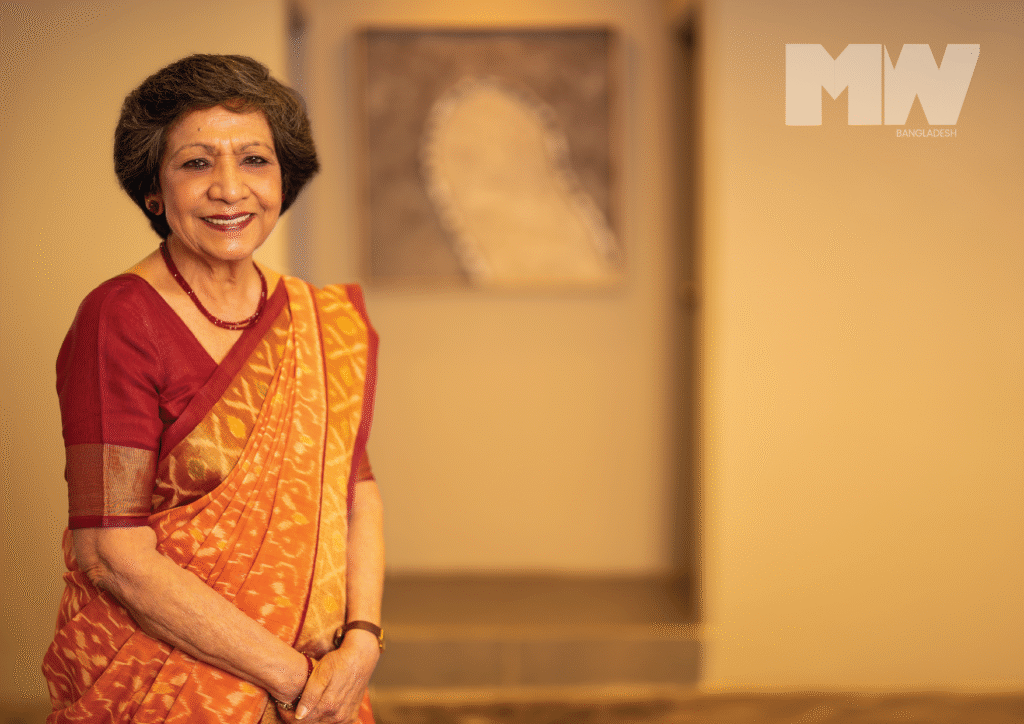

She has never asked to be called a “trailblazer.” And yet that’s what she is. Not just in advertising, but in the idea that women—Bangladeshi women—could build industries, shape culture, steer governments, and change narratives. And not just for herself, but for everyone watching in silence, wondering: “Can I do that too?”

To understand Geeteara Safiya Choudhury is not to chart a résumé. It is to travel through time, through corridors thick with resistance, where a woman learned to navigate ambition without apology, power without cruelty, and truth without compromise.

With MWB, this pioneering leader shares not only the milestones of her journey but also the roadmap she hopes young changemakers will use to build a better Bangladesh.

Breaking into a Man’s World

When Geeteara Safiya Choudhury first entered the advertising boardrooms of 1970s Bangladesh, she walked into spaces almost entirely occupied by men. “To be honest, it was very difficult,” she recalled. “I was always scared. I had to prove myself twice over—first as an entrepreneur and then as a woman. People didn’t think I could do anything on my own. They assumed I was just the face of my husband’s business, or my father’s, or my in-laws’.”

In an era when women were rarely seen in corporate spaces, Geeteara Safiya Choudhury had to constantly battle skepticism and prejudice. Questions like “Will your husband allow you to stay out so late?” haunted her. She remembers one client demanding proof that she really worked at the printing press at midnight to deliver a campaign on time. When the client eventually confirmed she was indeed there, he sent her a cake the next morning with a note that read: “Sorry, we misunderstood you. Keep up the good work.”

Moments like these were small victories—but they added up. Over time, they forged the foundation of one of Bangladesh’s most influential advertising agencies: Adcomm.

Proving Herself on Every Job

Choudhury’s career is filled with stories where instinct and honesty guided her decisions. One of her earliest lessons came from working on a lipstick campaign. She herself wore no makeup, but when an international consultant dismissed her opinion, saying, “What do you know about lipstick colors? You don’t even wear any!”—she didn’t back down.

“I may not wear lipstick, but my friends do, my relatives do. I see what they like,” she told him. She went out, surveyed women, and presented color swatches based on actual preferences. When the shades hit the market, they succeeded. What stung, however, was the consultant’s remark: “I don’t believe a Bangladeshi woman has this capacity.” Choudhury retorted sharply: “Excuse me, Bangladeshi women can do many things. Time will prove it.”

These stories illustrate her central approach: advertising was never about copying trends from abroad but about listening to people, observing culture, and grounding strategy in truth.

The Bamboo Ladder at Midnight

Another night, while preparing a stall at an industrial fair, she climbed a bamboo ladder to adjust displays at 1:30 AM. When she looked down, nearly forty men stood silently watching her. “I was terrified,” she admitted. “But my father had always told me, never show fear. Be brave.” She shouted at them to leave. They obeyed. Later, she discovered one of the men had actually been a contractor guarding the space.

Moments of fear turned into lessons of courage. “These experiences made me stronger,” she said. “Clients began to see me as someone who wouldn’t back down.”

Advertising as Nation-Building

For Choudhury, advertising was never a shallow exercise in slogans or pretty visuals. It was a tool to solve problems, build industries, and contribute to the country’s economic fabric. “I never thought I was just there to make money,” she said. “I wanted to help my industries grow, because when they grow, they recruit more Bangladeshis, my people get jobs, we produce locally instead of importing, and the economy becomes stronger.”

One of her most striking examples came from her work with a fertilizer and pesticide client. The company initially asked her to create television commercials. At first glance, it might have been the obvious choice. But Choudhury immediately thought of the target audience—the farmers in rural Bangladesh. “In those days, farmers didn’t have televisions. Even now, television is common in many homes, but back then, in poor households, it was rare. I knew the ads wouldn’t reach the people who actually needed the product.”

Instead of blindly following the client’s brief, she carried out her own field research. During a trip to Sylhet with her husband, she stopped wherever she saw farmers working. She climbed down from the car, approached them directly, and asked questions: What insects troubled their crops? What names did they use for these pests? Did they know how to use chemical pesticides? What challenges did they face with packaging?

What she discovered was eye-opening. The product names were long, technical, and nearly impossible for the average farmer to pronounce or remember. On top of that, packaging was done in one color to reduce printing costs—meaning that products for completely different crops and problems looked nearly identical on the shelf. Worse, insect names varied from village to village. “One insect might be called something in one place, and just two miles down the road, it was called something else,” she explained. “But farmers always knew their plants and their local names for the pests.”

With this knowledge, she developed a simple but powerful communication strategy. Instead of TV, she recommended radio advertising. Radios were everywhere—strapped to farmers’ waists, playing in tea stalls, and providing background noise even in the fields. Farmers listened while they worked. Radio would ensure the message reached them where they lived and labored.

To complement the audio message, she suggested redesigning packaging with distinct colors for each product line. The campaign would say: If your crop is attacked by this pest, use the product with the red label. If another pest, use the green label. If yet another, the blue label. This way, even if farmers could not read the technical names, they could easily recognize and recall which product they needed. She also pushed for posters as visual aids that could be displayed in local markets and villages, showing images of pests and the corresponding product color.

The client was skeptical at first, warning her that if it didn’t work, they would “sack her.” But Choudhury stood firm. “I said, okay, I’ll take that risk.” The campaign launched—and it worked not just adequately but spectacularly. Sales soared, farmers began using the products correctly, and the client’s trust in her grew immensely. “It worked miracles,” she smiled, still proud of the memory.

But beyond the professional triumph, Choudhury’s pride lay in what it symbolized. This wasn’t just an ad campaign. It was a way to bring knowledge to farmers, save crops, and strengthen local agriculture. “For me, it was about more than an agency’s success. It was about the country. If our industries grew, they wouldn’t need to import so much. They would hire more Bangladeshis, and that meant families would have jobs and dignity. If the country grows, the economy grows. And if the economy grows, everything becomes better for our people. That’s why I worked so hard.”

Her approach redefined advertising in Bangladesh. It wasn’t only about persuasion—it was about nation-building, about connecting industry to its people, about finding solutions rooted in cultural reality rather than foreign templates. In her world, every billboard, radio spot, or poster was not just a marketing exercise but a step toward self-reliance and progress.

Pioneering Gender Sensitivity in Ads

Choudhury was among the first in Bangladesh to challenge gender stereotypes in advertising. “Clients always wanted women cooking in ads. I said, why not show a man cooking? Men cook too. They just don’t admit it, but they’d love to brag about it if shown on TV.”

She insisted on portraying daughters as equal consumers in campaigns. “One client wanted only a boy drinking milk. I asked, why not a girl? If mothers see both, they’ll realize their daughters need nutrition too. That changes mindsets—and increases sales.”

Her philosophy was simple: advertising isn’t just persuasion, it’s cultural engineering.

A Cage of Bureaucracy

After decades of building Bangladesh’s advertising industry from the ground up, Geeteara Safiya Choudhury was unexpectedly drawn into government service. In the mid-2000s, she was appointed an adviser in the caretaker government, with charge of four major ministries: Women and Children Affairs, Industries, Social Welfare, and another key portfolio. For someone used to the urgency and creative problem-solving of advertising, stepping into the machinery of the state was an entirely different world.

“I honestly didn’t know the bureaucracy was that rigid,” she recalled. “Everything was slow, everything was tied up in rules, and the default answer was ‘Na, na, na.’ Files moved endlessly from one desk to another. In business, time is money. In government, time was just wasted.”

Her frustration was palpable. In advertising, she could pitch an idea in the morning and, if the client agreed, see it executed within days. In government, even the simplest proposal could take months to move forward. “They used to say, ‘It’s against the rules, Madam. You can’t do this.’ Even when something was clearly needed, they wouldn’t act for fear that someone would accuse them of having a personal interest.”

One particular episode remains etched in her memory. On her way to inaugurate a new factory in her capacity as Industries Adviser, she learned of a nearby orphanage. Drawing on her advertising instinct—always meet the end user, always understand people at the ground level—she decided to visit. “The Social Welfare Secretary told me not to go. He said, ‘You’re too high up for that. It’s not appropriate.’ But I insisted. I wanted to see with my own eyes.”

What she found shocked her. On the orphanage wall, a neat board displayed the daily menu:

Morning breakfast: chapati, fried potatoes, tea

Lunch: fish, lentils, rice, vegetables

Afternoon snack: biscuits, tea

Dinner: beef, lentils, rice, vegetables

But when she sat with the children and asked what they had eaten that day, every child gave the same answer: “Panta bhat ar alu bharta.” Fermented rice with mashed potatoes. Morning, noon, and night. “At first, I thought maybe one child hadn’t understood me,” she said. “But I asked again and again, and all of them replied the same. They weren’t getting what was written on the board. They were eating only panta bhat and alu bharta.”

She was devastated. “I couldn’t eat my own lunch that day. I kept thinking—I’m eating all these fancy things while these children have only mashed potatoes and rice.”

Determined to help, she reached out to General Amjad Khan Chowdhury of Pran, a respected industrialist. “I asked him, ‘Amjad bhai, can you support this orphanage? Give them rice, lentils—whatever you can.’ He agreed immediately. He said, ‘As long as my factory runs, these children will get food. I’ll even make it part of my will.’”

But when Pran attempted to deliver the supplies, the orphanage refused. The reason? “There was no tender.” Bureaucratic red tape had blocked even free donations. “It was absurd,” Choudhury said with exasperation. “They thought if I arranged this, I must have some hidden interest. I told them, ‘If anyone finds a single product from Pran in my home, hang me in public.’ Still, they wouldn’t accept it.”

For her, this incident symbolized everything wrong with the system. “Many bureaucrats want to do good. I saw it in their faces. But they’re trapped. They’re not given the freedom or authority to act. They’re afraid that if they step outside the rules, people will suspect corruption or favoritism. So, the safest answer is always ‘No.’”

After a year of wrestling with this culture of paralysis, she resigned. “I felt caged,” she admitted. “In advertising, ideas are about possibility. In government, ideas were smothered by paperwork and suspicion. It was suffocating.”

Her time in government did, however, leave her with one important conviction: the problem was not with individual bureaucrats, many of whom were sincere and wanted to help. The problem was structural. “The bureaucracy doesn’t empower them. They are not all corrupt, but they are fearful. They lack the space to take initiative. I even suggested sending civil servants to private-sector offices for internships—so they could see how efficiency and decision-making work in practice. But the system wasn’t ready for that kind of change.”

For a woman who had built her career on courage, improvisation, and quick problem-solving, the slow grind of bureaucracy was unbearable. “That’s why I left. I realized I could do more for Bangladesh from outside government than from within it.”

Local Storytelling as a National Duty

When asked why she always promoted local creatives over outsourcing to multinational ad houses, Choudhury replied passionately: “If I show something imported that people don’t understand, who am I doing it for? Even the elite are not fully connected to western culture. Our strength lies in our own stories, our own culture.”

For her, showcasing local culture wasn’t nostalgia—it was strategy. “Our culture is our brand. Women in villages do incredible work, but they are rarely shown. Changing that mindset through advertising is crucial.”

On Authenticity in Branding

In an age when branding has become almost synonymous with exaggerated claims, airbrushed imagery, and influencer-driven narratives, Choudhury’s understanding of authenticity cuts through the noise with disarming simplicity. For her, authenticity isn’t about creating a clever tagline or staging the perfect advertisement. It is about the integrity of the product itself.

“Authenticity,” she explained, “means a good product, a reliable product. Don’t over-exaggerate. If it’s bad, the consumer won’t buy it again. That’s the end of the story.”

This philosophy stemmed from decades of watching consumer behavior up close, not from boardrooms or spreadsheets, but from the ground. Choudhury built campaigns only after observing how people actually lived, worked, and consumed. In villages, she noticed how farmers carried radios tied to their waists while working in the fields. In city homes, she paid attention to what children preferred in snacks, how mothers made purchasing decisions, and how cultural aspirations shaped choices. Advertising could only succeed if it aligned with these realities. Anything else would collapse under the weight of its own dishonesty.

Her yardstick was always personal. “Make something you would use yourself, something you would give to your own family,” she said. “That is truth in branding. If you wouldn’t drink the milk you are advertising, if you wouldn’t eat the biscuit you are promoting, then you are lying—not just to consumers, but to yourself.”

This philosophy put her at odds with clients who wanted glossy exaggerations. Some would ask her to promise instant transformations—skin that turned fair overnight, shampoos that cured baldness, or miracle cures that solved problems in a week. Choudhury consistently pushed back. “If you overpromise, the consumer will buy it once, but they won’t come back. And in the long run, you destroy both the brand and the trust.”

She often reminded clients that Bangladeshi consumers, even those with limited literacy, were not gullible. “Our people may be poor, but they are not fools. They know value. They know when something is worth their money. Don’t underestimate them.”

For Choudhury, authenticity wasn’t only a moral position—it was also a practical business strategy. A satisfied consumer would return, spread the word, and build loyalty. A disappointed one would walk away forever. “Advertising can bring a customer to you once,” she would tell her clients, “but only the product can bring them back.”

Her insistence on authenticity also influenced how she framed cultural narratives in campaigns. She refused to show scenarios that were too artificial or divorced from everyday life. “I always said—don’t make the mistake of thinking our people want to see foreigners cooking foreign food in foreign kitchens. They want to see themselves. They want to see truth. That’s where trust is built.”

Even today, as brands race to hire influencers and flood social media with filtered images and scripted endorsements, her advice remains strikingly relevant. In her view, authenticity cannot be manufactured in a studio or through a marketing gimmick. It emerges from quality, honesty, and respect for the consumer’s intelligence.

Youth, Empowerment, and Her Children’s Lessons

She believes Bangladesh’s youth are more exposed to the world than ever before—but they must be taught confidence in their own country. “You are a second-grade citizen in a first-world country, but a first-grade citizen here. Be proud. Serve your country.”

Her own children embody that lesson. Her son studied at St. Stephen’s in Delhi, her daughter at the London School of Economics, but both returned to Bangladesh. “My daughter refused a lucrative international job, saying, ‘My mother taught me to serve my country.’ That’s the value system I wanted to pass down.”

Even succession at Adcomm was decided not by favoritism but through a neutral evaluator. “I didn’t want to choose between my children. If they mess up, the company dies. So, I brought in an outsider. After three months, he said, ‘The boy is better.’ Only then did my son become an MD.”

Standing Firm on Values

Choudhury never compromised her values, even when big money was at stake. When Fair & Lovely approached her, she initially refused. “I don’t believe a woman has to be fair to be pretty,” she told them. The client then showed her a research paper claiming 92.8 percent of Bangladeshi families discriminated against dark-skinned daughters. She agreed to handle the brand—but only if they funded women’s training programs in agriculture and fishing.

Her insistence transformed the campaign into something more than skin cream—it became tied to women’s empowerment.

From Home to Boardroom

Choudhury is candid about the struggles women still face. “People still think meyemanush parbe na—a woman can’t do it, especially at night. Violence against women is a real concern. But things are changing. Our girls are excelling in education, exams, careers. They’re more sincere and more devoted.”

The root of inequality, she insists, lies in families. “A woman’s biggest enemy is another woman—mothers who discriminate between sons and daughters, mothers-in-law who make life hard for daughters-in-law. Change has to start at home. Treat them equally. Divide property equally. That’s what I do.”

Her own mother-in-law, she emphasized, had been her biggest supporter. “When clients pushed me to start my agency, I was terrified. But my mother-in-law said, ‘Didn’t your father tell you, just do it? Then just do it. I’ll look after your baby.’ That encouragement made all the difference.”

Passing the Torch

Asked what values she wants to leave behind for future storytellers, she replied: “Be sincere. Be inquisitive. Give 100 percent of your attention. Look beyond Dhaka, beyond Bangladesh—see what’s happening in the world. But always be proud of your country. Bangladesh has achieved things the world can learn from. Love your country, and don’t be afraid to tell its stories.”

A Life of Courage and Conviction

Geeteara Safiya Choudhury’s journey is not just the story of a pioneering adwoman. It is also a story of a nation coming into its own—through its industries, its women, its stories, and its struggles against bureaucracy and prejudice.

Her voice carries the weight of lived experience: from midnight printing presses to boardroom showdowns, from government frustrations to grassroots empowerment. At every step, she insisted on truth—whether in products, in campaigns, or in life.

“Bangladeshi women can do a lot of things,” she said once in anger. Time has proved her right.

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Kaushik Iqbal

Assistant Stylist: Arbin Topu

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman