By Ayman Anika

On the first day of Boishakh – the first month of the Bengali calendar – Bangladesh bursts into a kaleidoscope of colors, sounds, and traditions. Streets fill with processions, the scent of hilsa and panta bhaat drifts from every corner, and people of all ages don colorful panjabis and saris to celebrate what is more than just a new year: Pohela Boishakh, a cultural heartbeat of the Bengali identity. But how did this vibrant day come to be? The history of Pohela Boishakh is as layered as the patterns of an alpana drawn on earthen floors – rooted in agrarian reform, shaped by emperors, revived through resistance, and polished by the people.

The Mughal origins: Calendar of the fields

The story begins in the 16th century with the reign of the mighty Mughal Emperor Akbar (1556–1605). At the time, taxes in the Bengal region were collected according to the Islamic Hijri calendar, which is lunar-based. But this created a mismatch between the Islamic months and the actual harvest cycles of Bengali peasants, leading to complications in tax collection. Recognizing the problem, Akbar introduced a revised calendar that merged the Islamic lunar calendar with the solar calendar used in Bengal and other Hindu-dominated regions. This reform, known as Fasli San or the “harvest calendar,” was implemented around 1584 to ease tax administration.

Historians believe that the reform was not just bureaucratic – it sowed the seeds for a cultural ritual. On the last day of Chaitra (the final month of the Bengali year), peasants would clear off their dues, and the following day, Pohela Boishakh, would be celebrated as a fresh beginning, often with sweets and social gatherings. Over time, this administrative practice turned into a festival of joy and renewal.

Photo Source: Met Museum

.

The agrarian heartbeat

Bengal, with its river-fed lands, has always been an agricultural society. The Bengali calendar closely follows the seasonal cycles – Boishakh welcomes the intense heat and rains that fuel the planting of paddy. Naturally, a day that marks the start of such a critical season evolved into a time for not only celebration but also reflection and preparation.

In rural Bengal, especially among farmers, Pohela Boishakh became a day to clean homes, bathe livestock, and settle debts – both material and spiritual. Traders and shopkeepers, particularly Hindu and Buddhist merchants, would open a new haal khata (ledger book) after conducting a puja, inviting customers to settle old accounts and begin anew. This tradition still continues, notably in places like Old Dhaka and rural marketplaces.

The cultural embroidery of a nation

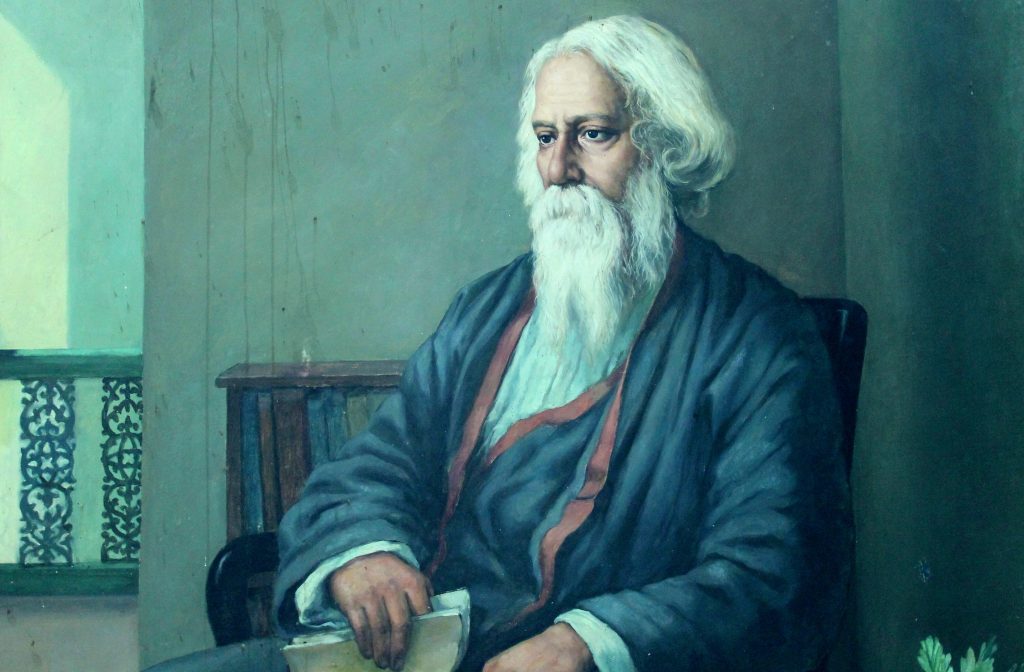

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pohela Boishakh was not just a rural agrarian festival – it was being embraced by a broader swath of society. With the rise of Bengali nationalism under British colonial rule, cultural icons like Rabindranath Tagore began associating seasonal celebrations with literary and artistic movements.

Tagore’s compositions – many written to celebrate the six seasons of Bengal – became staples in Barsha Mangal and Boishakh programs. His songs added intellectual and emotional depth to the day, weaving poetry into the cultural identity of the new year.

Photo Source: Jadavpur University

However, the most iconic turn came post-Partition in 1947, and especially after the formation of East Pakistan. In a state increasingly pressured to conform to a monolithic Islamic identity, Bengali language and culture faced systemic marginalization. The resistance to this came not only through political struggle but through cultural assertion.

From protest to procession: the rise of Mangal Shobhajatra

In 1989, amidst the autocratic regime of Hussain Muhammad Ershad, students and teachers of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Dhaka organized the first Mangal Shobhajatra (procession of well-being) to resist fear and oppression with creative courage. They crafted giant masks and effigies – stylized animals, birds, and mythical figures – symbolizing the struggle between good and evil.

Since then, Mangal Shobhajatra has become the face of Pohela Boishakh in urban Bangladesh. The UNESCO recognition of this procession in 2016 as an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” only reaffirmed its importance as a non-communal, people’s celebration that bridges class, religion, and politics.

A secular, inclusive celebration

Pohela Boishakh is perhaps the most secular and inclusive festival in Bangladesh. While it has roots in both Hindu and Muslim traditions, its modern-day avatar celebrates humanity. It is common to see Muslims, Hindus, Christians, and Buddhists participating together in fairs (Boishakhi melas), music performances, poetry recitations, and traditional plays.

It is also a day of conscious aesthetics – people wear white and red, cook traditional meals, and gather under the shade of banyan trees or in cultural centers like Ramna Botomul to welcome the day with songs like “Esho he Boishakh, esho esho.”

Photo source: Wikipedia

The commercial and contemporary touch

Today, Pohela Boishakh is also a time for booming business. Fashion houses unveil new collections, restaurants offer special menus, and media channels produce elaborate programs. Some critique this commercialization, but others argue that the evolution reflects the adaptability and relevance of Bengali culture.

A day that belongs to everyone

In a world that often tears communities apart based on language, religion, or race, Pohela Boishakh stands as a radiant exception. Born from necessity, nurtured by poets, emboldened by protest, and celebrated by all, it is more than just a new year – it is a testament to the Bengali spirit of unity, resilience, and joy.

As the sun rises on April 14th, the air again rings with voices singing “Esho he Boishakh.” And once more, the past meets the present in a celebration that is, at its core, a hopeful promise of beginnings – pure and timeless.

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman