By Abak Hussain

“To tell the truth, no one was looking down on me except myself.”

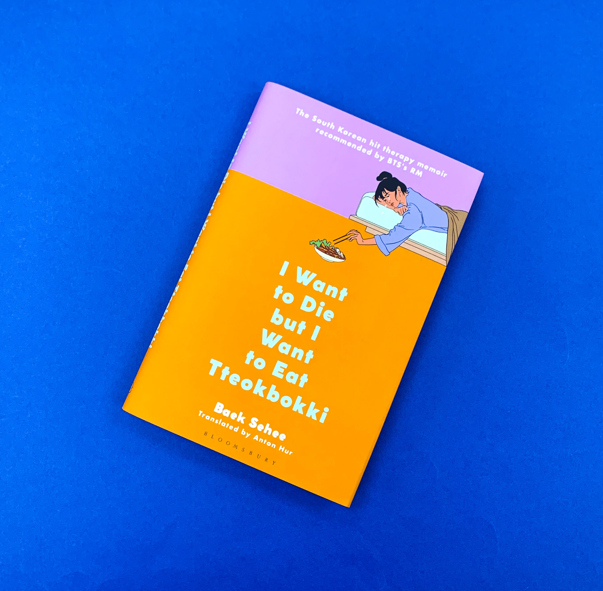

South Korean author Baek Sehee, whose frank and vulnerable account of her mental health struggles turned her into a literary phenomenon, has passed away at the age of 35. There is little doubt that in the seven years since the publication of her best-seller I want to die but I want to eat Tteokbokkii her words have affected countless people – who knows how many lives she saved. Here are some testimonials, printed on the back of my copy of the book: “While reading, I remember thinking ‘so other people live like this too’ and sometimes that can be the most comforting thing to realize.” “If there is one word to sum up this book it is: seen.” “The unique feeling of knowing someone in the world is not OK right now either. And both of you will be fine.” It is rare to find a book so starkly honest about one’s own trauma and resulting mental health crisis. It shows how complicated mental health issues can be and that progress is never linear. We heal, we regress, go back and heal again. Baek Sehee’s family has not officially disclosed the reasons for death, but even if the case is that she finally succumbed to the demons that plagued her since childhood, her work is likely to continue having a positive impact and bring about greater awareness of mental health issues that affect society today.

Her first book (the first of the two I want to die books) was published in 2018, and at the tender of age 28, Sehee found herself the author of a smash hit. Who knows just how the success affected her. She did go on to write a sequel in the same vein. The 2018 book is an act of tremendous courage, especially for someone who confesses to having deep self-esteem issues or harbouring dark thoughts and petty feelings. The book is slim, and most of it consists of transcripts of Sehee’s conversations with her therapist. With consent of her therapist, she recorded her sessions, and went home and reproduced them onto the page. These unglamorous conversations became the basis for the book, to which Sehee adds her own notes and reflections on her progress.

“I’m sad but I’m alive,” she writes, determined with all her waning energy to pull herself out of the dark pit in which she finds herself. Sehee talks about her abusive father, her complicated feelings towards her older sister, her unhealthy patterns at work with her colleagues, her self-image issues which may have bordered on body dysmorphia. In the end, perhaps, by publishing these conversations, she was able to help others more than she was able to help herself, but then, therapy was never supposed to be a magic bullet. Just like with any physical illness, sometimes the damage on the inside is too deep to overcome in spite of our best efforts and best intentions. There is something about the hardware of the brain that makes us wipe clean our progress and revert. We may become aware of our own harmful patterns, say, the tendency to engage in unhealthy social comparison, we may resolve to overcome those patterns, but we often lapse back. The grooves are too deep, the wounds are too permanent. Regressing can, unfortunately, cause a spiral – after relapsing into unhealthy mental habits, we may observe our regression and further lose hope and motivation.

Baek Sehee admits in many of her therapy sessions that she often envied others and suffered from low self-esteem. Her own life, though tragically cut short at the age of 35, from the outside looks like a stunning success. Sehee, with her hyper self-awareness surely knew this. She was born in 1990, the middle child of three daughters. Though her early family life was troubled, at university she was able to study exactly what she wanted to study – creative writing. She went on to secure what would fit the bill as her dream job – in the publishing industry. There is very little evidence that she was grossly mistreated at work. If anything, her bosses were compassionate, and when she wanted to quit the job the company suggested she could take a break instead and try coming back later – an act of kindness Sehee herself admits brought tears of gratitude to her eyes. She underwent therapy for a decade, turned her unvarnished truth into books. The raw material of her mental health struggles turned into two runaway hits: I want to die but I want to eat Tteokbokki and its sequel I want to die but I still want to eat Tteokbokki. Every creative writing major dreams of making it as an author. Baek Sehee certainly more than achieved that dream. At the time of her death, her work had already been published in 25 countries, with over a million copies sold. In time, no doubt the readership will grow.

But dysthymia, the persistent gnawing brand of depression that Sehee suffered from, had very little to do with outwardly success, or the trappings of it. Often many of us are told, “your life is so good, what do you have to be depressed about?” or “cheer up!” or “I would love to have what you have.” These maladies, however, have complex origins and often require deep work and even then the battle can be too steep. We wouldn’t tell a cancer patient to “snap out of it” and we wouldn’t tell someone with a broken bone to start walking because “other people have it worse.” As a society, we need an improved awareness of just what mental health comprises of. In fact, those who deride trips to the therapist are often the ones who really most need therapy. Alas, we cannot force them to seek help. We can only try to help and heal ourselves. Baek Sehee certainly did, with every morsel of will she could muster, and in spite of the darkest depression, she was able to contribute a piece of work to the world that I am sure will prove to be of lasting value, and will be studied and discussed in classrooms and seminars around the world.

“The important thing isn’t whether you are being loved, it’s how you will accept the love that comes your way,” is one of the many powerful insights she shares with the reader. What an extraordinary spirit! May she rest in peace.

Abak Hussain is Contributing Editor at MW Bangladesh.

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman