By Ayman Anika

When Monirul Islam first picked up a pencil, he didn’t know he was making art. Growing up in pre-independence East Pakistan, in a quiet town where art was more likely to appear on the back of a rickshaw than in a gallery, he was drawn to forms, textures, and the silent rhythm of shapes. What surrounded him wasn’t institutional art – it was cinema banners, folk motifs, and the everyday beauty of handmade objects.

Over time, that early aesthetic instinct evolved into a lifelong visual language. From his days as a young teacher at Dhaka’s Art College in the politically charged late 1960s to his accidental journey to Spain on a scholarship, Islam’s life has been shaped by intuition, displacement, and the stubborn persistence of creative clarity. He arrived in Madrid without language, without a plan – only with a sketchbook and a curiosity to see what lines might lead him forward.

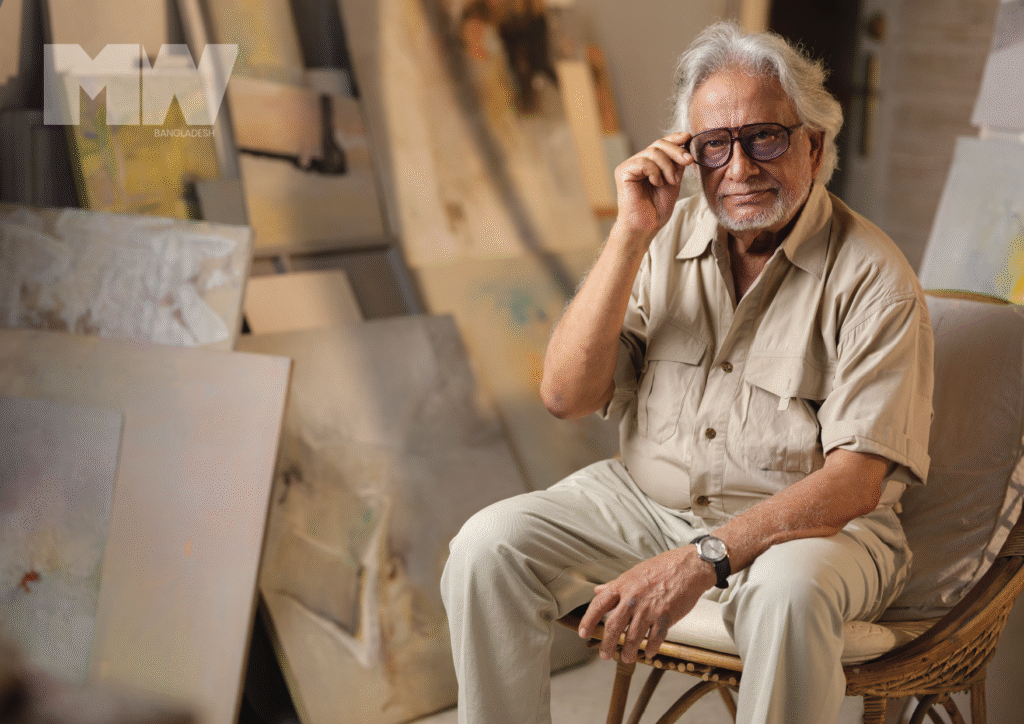

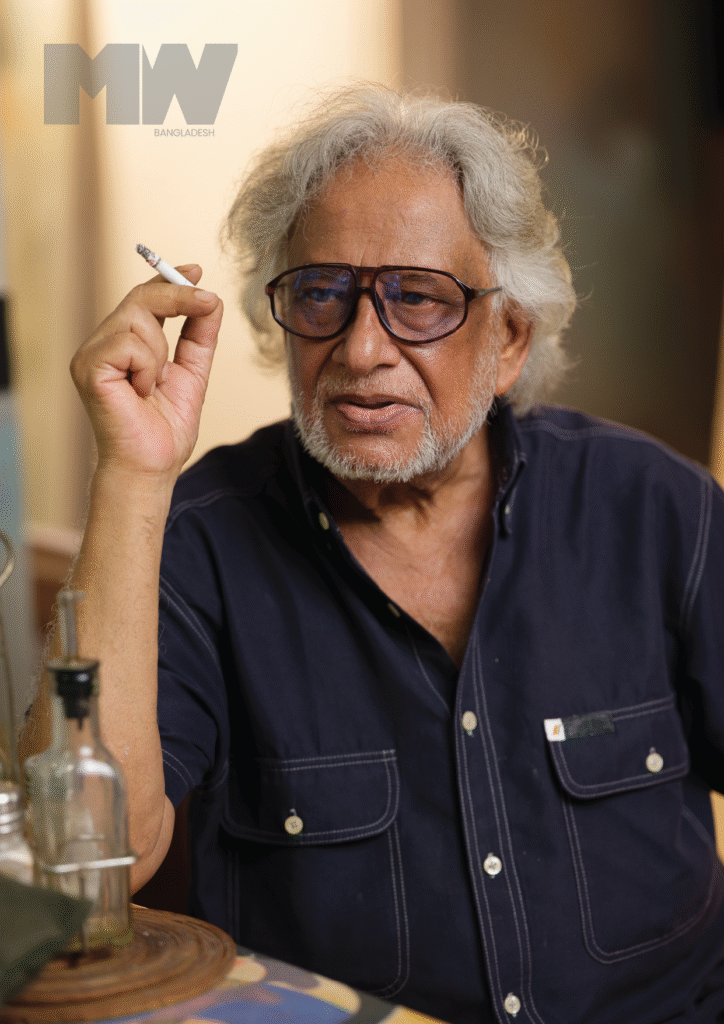

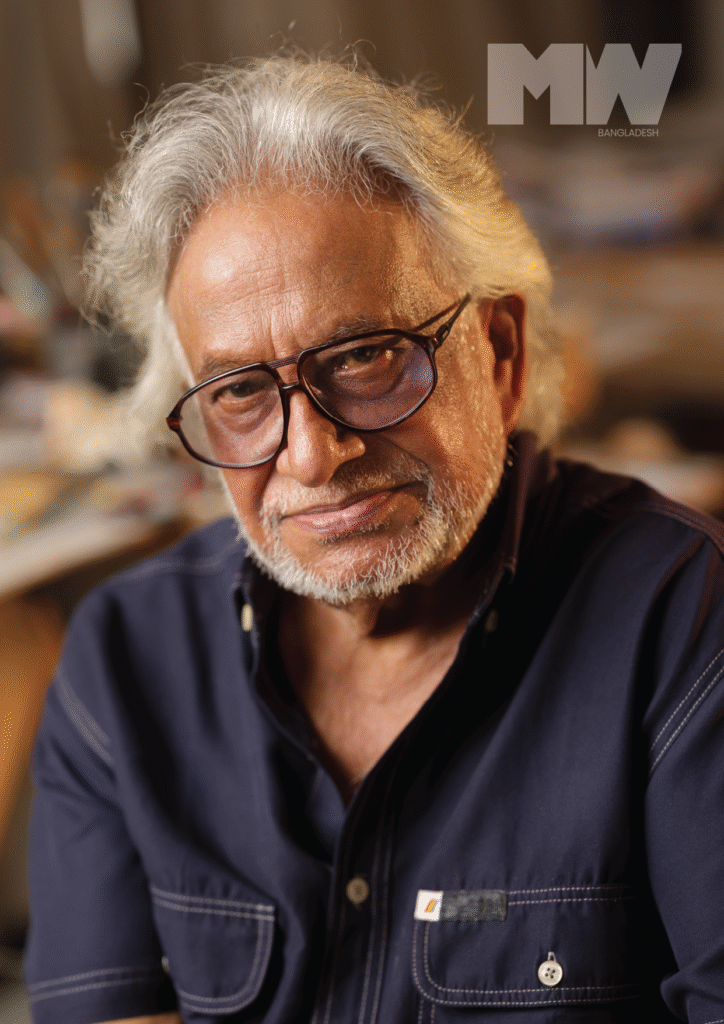

Now in his 80s, he speaks of color not as pigment, but as energy. He speaks of abstraction not as a style, but as a universal condition. He says, “I don’t paint the rose. I paint its scent.” Through etching, paper, and forms that seem to emerge from silence, Monirul Islam has built a practice that resists definition but invites reflection.

In this interview with MWB, the veteran artist reflects on his lifelong relationship with art, the lessons he’s gathered through struggle and solitude, and the layered journey between two homes – Bangladesh and Spain.

You were born in 1943, before Bangladesh became a nation. What are your strongest memories from that time? Was there a love for art even then?

What stands out most to me about that time is the quality of life—and particularly, the quality of education. During East Pakistan’s era, institutions like Dhaka University were deeply respected, not just locally but internationally. I remember seeing students from Africa, Iran, and Turkey come to Dhaka to study. It was a place of excellence. We had that dignity. But over time, that standard has deteriorated. I’m not an education expert, but from what I observe, even basic literacy seems fragile now.

The greater loss is moral. Our sense of decency, our empathy, our dignity—it’s all slipping. Once a country loses its morals, it’s very difficult to get them back. In countries like Bhutan or Nepal, there’s still a visible grace. Here, you land at the airport and feel the irritation in the air.

Suspicion, impatience, even hostility—it’s all too common. That wasn’t the case before. Back then, we were fewer in number, yes—but also more grounded. There was respect, even among friends, a kind of unspoken dignity. And I believe dignity is everything. Even a beggar can possess it. But today, you see people with wealth and education who lack it entirely.

Everyone’s chasing money and fame now, including me, including you. We’ve created a society that compares endlessly—cars, apartments, status. But what’s the point? In the end, we’re all just temporary. We come into this world empty-handed and leave the same way. We are, in essence, rented beings. No one takes anything with them.

As for art, yes—perhaps there was something there from the beginning, but we didn’t understand it then. Children often express themselves through drawing before they learn to speak. When a child draws, they don’t see the ground or the horizon—just floating forms. It takes a few years before that horizon appears.

They begin to crave realism, but their hands can’t yet follow. And that’s beautiful. Picasso once said, “A child is the best artist.” I agree. Children are spontaneous, fearless. They’ll mix yellow with black without hesitation—something we trained artists rarely dare to do. They have courage. Our minds, on the other hand, are cluttered with rules, with museums, with comparisons. We’ve lost that innocence.

“Art is the only universal language.

It has no racism, no boundaries—only feeling.”

Even so, there must have been a quiet corner in me where aesthetics lived. I used to enjoy handicrafts—cutting paper decorations with scissors. But you must understand: back then in Kishoreganj, art was not a known or spoken thing. It existed in cinema banners, in the backs of rickshaws, in signboards. And I found beauty there—especially in those film posters. They had colour, drama, and emotion. I still like them. Rickshaw painting, too—there’s something wonderfully honest and humorous about it. It was rural pop art, in its own way. Sadly, even that is disappearing. Along with it, we’re losing the empathy and sensitivity that once made life beautiful.

Now, we live in an age of science and speed. In the last 50 years, the world has changed more than it did in the previous 5,000. Technology has made life easier, yes—but not necessarily better. We don’t use it wisely. We take health for granted, we believe we’ll live forever, and then run to doctors only when trouble comes. There’s a kind of blindness in that.

And when I think globally—Africa, for example—I see how deep-rooted these inequalities are. The West has always kept certain countries at a distance. The symbolism is powerful. “Black” still equals danger. “Pink” equals dreams. Colour itself has become loaded with meaning—just like a traffic signal: green means go, red means stop. You don’t need words anymore. But when everything becomes symbolic, abstracted, and categorized, we sometimes forget how to simply feel.

So yes, I suppose I was always drawn to beauty—but I didn’t know how to call it “art.” Not yet.

When did you first begin to understand color—not just as something we see, but as something that can be used expressively?

Understanding color isn’t something that comes instantly—certainly not at the age of three. In fact, scientifically, it’s said that when children are born, they don’t even perceive the world in full color.

Many believe they initially see in black and white, in tones of grey. Gradually, as vision develops, color enters perception. And even then, some people remain color-blind for life—who confuse red with green, or see no distinction at all. So color, first and foremost, is not a given. It’s something we come into over time.

But once we do begin to see it—really see it—it becomes something much more than just visual data. It becomes a language. A medium of expression. That’s why we surround ourselves with color: in clothing, in homes, in rituals, even in food. Color isn’t exclusive to painting. It lives in every part of life.

And it’s important to remember—color only exists in light. Without light, there is no color. In darkness, everything turns black. And black, really, isn’t even a color in the traditional sense. It is the absence of color. When we discuss colour, we are also referring to light, perception, and existence.

Take food, for instance. In Barcelona, where I’ve lived for many years, there’s a famous food fair—a gastronomy festival. People from different regions of Spain present their traditional dishes, and one of the most fascinating aspects is how color plays a role even there. They don’t just cook to feed; they cook to express. The colors in their dishes are vivid—bright reds, greens, blacks—sometimes so intense, it feels like you’re eating color itself. It’s a sensory experience.

So, for me, color has always been more than just pigment on canvas. It’s emotional. It’s symbolic. It’s functional. It communicates mood, movement, memory. It shows up not only in what we make, but in how we live. Color is everywhere—it’s one of the most basic ways we respond to the world around us.

And perhaps that’s why it took time to fully grasp its power. Not just how to use it, but how to feel it.

Did the political changes of the time—the partition, the Liberation War—ever make their way into your art, even if indirectly?

Not directly, no. But these things live in the background. You begin to see them over time. Take something as simple as a flag—it’s never just a flag. During the Pakistan era, the flag was green, with a crescent moon and a white star. Green symbolized youth, hope, and Islam. It was all very symbolic. But symbolism can only hold a country together for so long.

At first, there was no visible problem. We were told we were brothers—East and West Pakistan. But over time, the imbalance became clear. East Pakistan was where the “grass” grew—meaning the labor, the resources, the people—and West Pakistan drank the milk. They built Islamabad with our money, with our taxes. We were the majority in number, yet treated like the minority. Eventually, we realized: no, this isn’t brotherhood. This is exploitation.

The seeds of separation were planted slowly. You cannot form a country based only on religion. If you said today that Spain and Hungary should be one country because both are Catholic, it wouldn’t make any sense. But that was what Pakistan was—a forced union. We were completely different in language, food, and race. They ate roti. We ate rice. They spoke Urdu; we spoke Bangla. Even our physical features were different.

And then there was the language issue. When Jinnah came to Dhaka and declared at Ramna Park that Urdu would be the sole state language, people resisted immediately. He repeated it three times, but the answer from the people was clear: “No.” If we hadn’t stood up then, this country might never have had its own language, its own identity.

The political shifts, the betrayals, the movements—they shaped me.

And through me, perhaps, they shaped my art.

So, while these events may not have directly appeared in my paintings as political symbols or scenes of war, they shaped my understanding of identity—of what it means to belong. These experiences, these divisions, these fights for voice and space—they are in me. And anything that is in you inevitably seeps into your work, whether you’re aware of it or not.

And of course, language matters deeply to me. Bangla is one of the most spoken languages in the world, but its global presence is still minimal. Outside of Bengali families, it is rarely heard or practiced. While UNESCO has recognized the richness of Bangla—its songs, its literature, its linguistic heritage—the world does not truly engage with it. We talk about preserving culture, yet we are quick to abandon our language for convenience.

So yes, the political shifts, the betrayals, the movements—they shaped me. And through me, perhaps, they shaped my art.

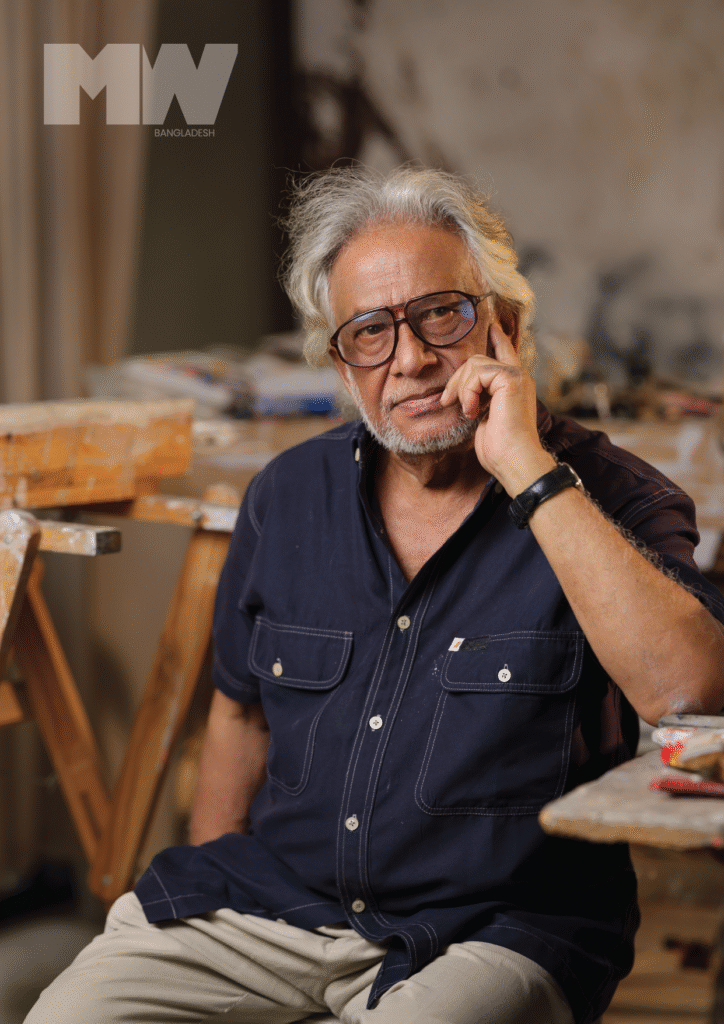

When you first arrived in Spain, what did it feel like to make art in a completely new country—especially when you didn’t speak the language?

When I first went to Spain, I didn’t know a single word of Spanish. Not even a greeting. It was all completely foreign to me—language, culture, geography. To be honest, I hadn’t even left the borders of East Pakistan before that. I hadn’t visited West Pakistan. I hadn’t even traveled across all the provinces of what is now Bangladesh. And suddenly, I found myself on a plane to Europe, on a nine-month scholarship, with a suitcase of uncertainty and only thirty US dollars in my pocket.

You see, it wasn’t part of some grand plan. It happened almost accidentally. At the time—this was 1969—the political situation in East Pakistan was volatile. The war hadn’t started yet, but the tension was thick in the air. Art College had become a hub of resistance. Posters, handwritten manifestos—all of that came out of our studios. We were at the heart of it. I was teaching at the time. The youngest teacher.

One day, I was walking down the stairs at the college when Rafiqun Nabi—my contemporary, a fellow teacher—asked me casually, “Are you going to Spain?” I laughed and said, “Why don’t you go?” He replied, “Do you know, one of our teachers has been trying to apply for this scholarship for 15 years?” Back then, all scholarships were handled centrally by West Pakistan. Everything was controlled, bureaucratic. An announcement would appear in a newspaper just seven days before the deadline. And for that, you’d need 12 different certificates! Things that would take three months to collect.

But somehow, I managed to send in an incomplete form with a trace of hope. And then, four months later, a telegram arrived. I had been accepted. It was a diplomatic scholarship—a cultural exchange. One Bengali would go to Spain; one Spaniard would come to Pakistan. That’s all it was. Merit wasn’t really a factor. It was about protocol, diplomacy.

But the challenge was real. My monthly stipend was 30 dollars. The plane fare to Madrid was Tk 4,000. And my salary at the time? Just Tk 200. To put it in perspective: today, you can’t eat lunch in Gulshan for that amount. But back then, it was everything I had. However, with help from some good-hearted people, I got the ticket.

So, I flew to Spain without knowing the language, without knowing anyone, with just a 9-month promise and my art.

And yet, something strange happened: I found that art was enough. In Spain, I didn’t need to speak fluently to be understood—my sketches, my prints, my brushstrokes spoke for me. I slowly picked up Spanish, yes, but what helped me survive wasn’t words. It was color, line, texture. Art became my first and truest language.

It changed me. And it was never meant to be forever. I was supposed to return after nine months. But life turned, as it often does. And Spain became a second home.

People often say I was the first non-Spaniard to receive certain recognitions there. That’s not entirely accurate—Rashid Chowdhury went before me, on the same scholarship. But yes, over the years, I received many awards—not just in Spain, but from Vienna, Yugoslavia, Norway, Finland, and of course, Bangladesh: the Ekushey Padak, the National Etching Award, many others.

But I never made a shrine for them. No closet full of medals near the entrance of my house. There’s too much obsession with awards nowadays. I didn’t go to Spain for glory. I went with curiosity. And maybe that made all the difference.

Were you the only Bengali there at the time?

Yes. For almost ten years, I was completely alone as a Bengali in Madrid. There were no other Bangladeshis. The only person I met from our region was a Bengali from Bardhaman, West Bengal. He was quite the character.

He was free-spirited—liked to teach yoga and talk philosophy. We connected through shared culture, not shared citizenship. Back then, the world was smaller, and the solitude was larger. But we still found our ways to belong.

Did the 1970s spiritual wave from India—Ravi Shankar, George Harrison—touch Spain too?

Very much so. That era saw a cultural fascination with the East. Ravi Shankar, George Harrison, the Beatles—they had introduced the West to sitar, to transcendence. George Harrison helped organize the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh. That spirit of artistic exchange and curiosity was alive in Spain, too. Even without a common language, people were interested in yoga, music, and mysticism. It helped create a cultural atmosphere that was open to someone like me—an artist from East Pakistan, speaking in lines and colors instead of fluent words.

You had the rare privilege of learning from great minds such as Zainul Abedin and Mustafa Monwar. What was it like to learn from them?

Learning from Zainul Abedin and Mustafa Monwar wasn’t just about mastering technique—it was about being in the presence of integrity, imagination, and deep humanity.

Zainul sir was not a regular instructor when I was studying, but he would often visit the college. We, his younger students, would gather at his home for adda. He loved to talk, to share, to scold lovingly. I consider myself incredibly lucky—perhaps the only artist in Bangladesh—who had the privilege of sitting beside him and drawing twice on rented boats in Chandpur. Those moments weren’t formal lessons, but they were lessons all the same. His words still stay with me. Once, when I told him I was going to Spain, he gave me advice I carry to this day:

“If you must run, don’t run behind a lame man—run behind a champion.”

Simple. Direct. But profound. It meant: follow greatness, not mediocrity. Let your artistic pursuit be shaped by excellence.

He had an incredible sense of style, too—always neatly dressed. I remember his olive green Hawaiian shirt, crisp white trousers—ironed, refined. At a time when most people in Dhaka wore cotton, white shirts, and panjabis, he stood out with quiet dignity.

Mustafa Monwar was another kind of teacher—soft-spoken, gentle, and exceptionally intelligent. He had a unique way of looking at the world, and his wisdom went beyond the canvas. We were close. I still have memories and materials from our time together. What I gained from him wasn’t just artistic knowledge—it was a way of thinking.

What has stayed with you most from your time with Zainul Abedin?

His clarity. His directness. His humor. He once told me, “Go to Spain. The women are beautiful, the art is strong, and the sky is clear.” And then he laughed. He would say things that seemed light but carried weight.

He encouraged me not by giving me a long lecture, but with a few sharp strokes of truth. I didn’t just learn how to draw better—I learned how to live with more intent. And maybe that’s what great teachers give you—not just skills, but vision.

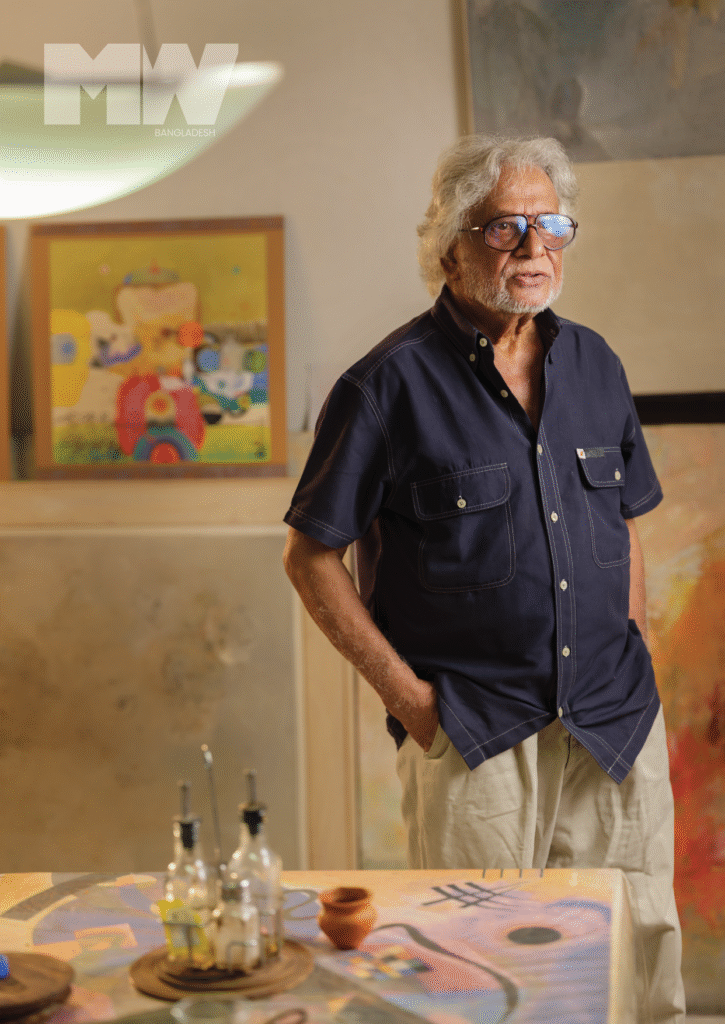

Spain has a rich cultural past. Did it influence your artistic vision?

Deeply. Spain has Arab blood in its roots—800 years of Islamic history. The Cordoba Mosque, the Alhambra Palace in Granada, the city of Toledo, where Jews, Christians, and Muslims once lived in harmony—these places shaped me. I’ve visited them many times, drawn them, felt their echoes in my work.

The Islamic tiles, their design philosophy—repetition, rhythm, no empty space—they remind me of our own alpana. Nothing is wasted. Every inch carries meaning. Even Escher, the famous Dutch etcher, was inspired by the tiles of the Cordoba Mosque. The Arab influence in Spain is still visible—food, architecture, even pride. Spaniards openly say, “We carry Arab blood.” No other European nation says that.

And yet, that legacy is often erased by modern geopolitics. Look at the Middle East—Palestine, Iraq, Syria, Libya. So many bombs. So much loss. Islam today is seen through the lens of violence, not culture. But this was a civilization that once led the world in science, literature, mathematics, design.

What has etching taught you that other mediums haven’t?

Etching didn’t just teach me technique—it taught me how to survive, how to endure, and how to speak when language failed.

It spread on its own. The galleries I worked with would often take ten pieces at a time. From that point, I never had economic difficulties. I managed my entire life through etching. But it didn’t come easily. I lived for five years in an abandoned house outside Madrid—no toilet, no bathroom. Just four tiled walls. It was a war-like time. My scholarship money had been cut off—the ambassador himself stopped it—and suddenly, I found myself on the street. I had to fight for everything. And in some ways, that fight continues even now.

Etching gave me a discipline I hadn’t known before. You have to prepare the plate, soak the paper, calculate time, understand acid, and wait. It’s a medium that teaches patience and control—and also, the acceptance of imperfection. Sometimes the plate doesn’t behave. Sometimes the line rebels. But it also surprises you. It taught me to surrender, to listen.

But more than that, etching opened doors. Real doors. Awards. Recognition. Respect. But even then, there’s an invisible ceiling. Every country wants to promote its own artists. A French gallery will uplift a French artist. A Spanish institution will prefer its own. They will only recognize you—a foreigner, a Bengali—if your work surpasses their own. That’s the harsh truth.

But art shouldn’t work that way. Art is a universal language. It doesn’t have borders. It doesn’t carry racism. Yet, we still see those boundaries drawn. And so, etching taught me the value of persistence—not just artistic persistence, but human resilience. It’s not only about making images on metal. It’s about making space for yourself in a world that isn’t built for you.

That’s what etching taught me.

What do you think of the current art scene in Bangladesh?

I would say the artists in Bangladesh today are doing remarkable work—and they’re doing it with courage. There’s a certain freedom in their work, a willingness to explore beyond the boundaries. And perhaps one reason for that is that Bangladesh, being a relatively young nation, doesn’t have the burden of centuries of rigid tradition in the way that, say, India does.

In India, art is still often tethered to mythological narratives—Ramayana, Mahabharata, the deities. That weight of tradition can become an obstacle. They haven’t broken free of it yet. I’ve served as a jury member for the Bharat Bhavan Biennale in Bhopal several times, including the first one, and I’ve seen it firsthand: the mythological themes dominate. But in Bangladesh, our tradition is mostly folk-based—things like Nokshi Pitha. Think about it. In a remote village, someone spends hours designing leaves and birds into a rice cake. The taste doesn’t change, but the aesthetics do. That instinct for beauty—that is art.

People often tell me, “Bhai, I don’t understand your paintings.” And I tell them, “Neither do I.” Then they stare at me. But that’s the truth. Art isn’t always about understanding—it’s about feeling. I explain it this way: “Instead of painting the rose, I try to paint the scent of the rose.” That’s where the unseen world begins. Love, jealousy, sorrow, hope—none of these are tangible, yet they shape our lives. And that’s what abstract art reaches for.

“People say they don’t understand my paintings. I tell them, I don’t either. That’s why I paint.”

When we were young, we had nothing—no good paper, no colors, no gallery, no museum, and certainly no internet. If we wanted to see art, we had to imagine it. There were no reference books. Now, everything is in your pocket. This phone—it’s a prophetic device. From your kitchen, you can see the museums of Paris, New York, or Tokyo. You can talk to a friend in Australia and show them your latest sketch. Millions of artists are working at this very moment, and we can access their work instantly.

Today’s generation has immense opportunities—but also greater pressure. Because with so much available, it’s not enough to simply make art. One must now ask: What am I adding to this enormous, noisy, global conversation?

What would be your message to young artists?

Art today has become a puzzle. There are so many forms, so many movements—realism, abstraction, Fauvism, surrealism, pop art, installation, performance, digital. These forms, these mediums—oil, watercolor, charcoal, sculpture, ceramics—they are all just tools of expression. But the real question is: What are you expressing, and why?

Young artists must understand this distinction. Don’t be swept away by trends imported from the West. These movements—what we now consider “modern”—emerged in Europe a hundred years ago. We are late arrivals. But being late is not the problem. The real danger is copying without knowing who you are.

If I play the dotara, I cannot perform a Mozart concerto. It will never work. And if I try to learn both Lalon and Beethoven at once, I will lose both. An artist must anchor themselves in their own rhythm. Find your own tone first—your own soil, your own sky. Otherwise, your expression will be borrowed.

“Instead of painting the rose, I try to paint the scent of the rose.”

In Association With City Bank

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Kaushik Iqbal

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman