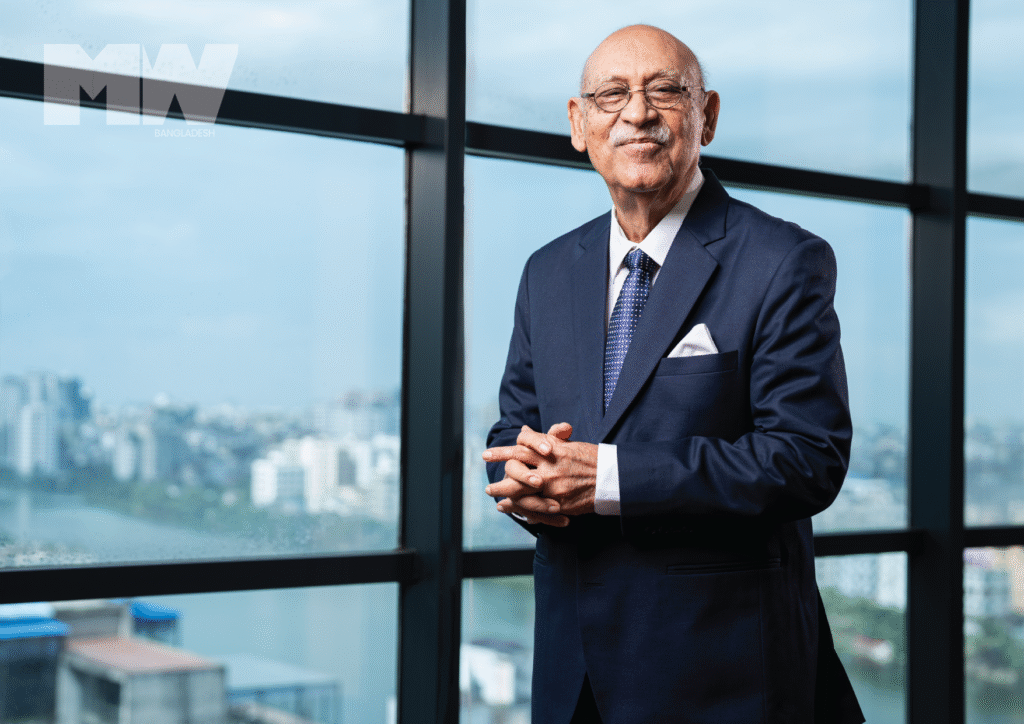

Engineer by training, actor by instinct, director by habit, and writer by curiosity—he has moved through Bangladesh’s cultural landscape like someone quietly rearranging the furniture while the rest of us were too busy watching the show. In a career spanning over five decades, Abul Hayat has been a familiar face across stage, screen, and television—not as a brand, but as a presence. He never chased roles. He just showed up and stayed.

By Ayman Anika

He speaks in a measured tone, pausing often, weighing words not for their weight but for their usefulness. There’s no interest in self-mythology. Childhood, he’ll tell you, was about fabricating curtains out of bedsheets to stage make-believe plays. Acting didn’t arrive as a calling—it simply fit. Engineering paid the bills. Writing came later, not out of ambition, but because some thoughts demanded paper. His belief in discipline is as quiet as it is firm. His advice to younger artists is grounded in lived experience: learn the craft, respect the process, and don’t dream so big that you forget to live small.

There’s a practical elegance to the way he thinks—about work, fame, failure, and what lasts. He doesn’t romanticize the past, nor does he mourn its passing. He’s observed Bangladeshi media shift from makeshift TV sets to the world of OTT, and through it all, has remained anchored—open to change, but never eager to chase it.

In conversation with MWB, Abul Hayat reflects on his childhood, his many roles, and what it means to carry on—not for legacy, but because the next scene still needs doing.

What are your most vivid memories of growing up in Chittagong – did the theatre rehearsals at the Railway Club leave a permanent mark?

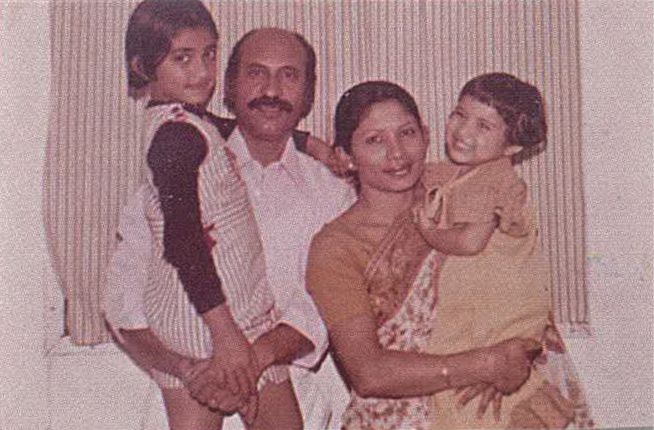

I moved to Chittagong when I was only three years old. I was born in 1944 in Murshidabad, and after the Partition in 1947, our family migrated to what was then East Pakistan. So naturally, I don’t remember much of my life before Chittagong. But everything that shaped me—the foundation of who I am today—started there.

We lived in the railway quarters because my father worked in the railway service. And let me tell you, the railway had its own culture—a vibrant, almost self-contained world. Wherever there were railway headquarters, whether big or small, there were always auditoriums, regular cultural programmes, music, and theatre. Chittagong, being the headquarters of East Pakistan Railway, was no exception. It had a thriving cultural scene. Every month there would be a play, musical night, or variety show. Rabindranath’s and Nazrul’s birth anniversaries were celebrated with great enthusiasm.

This was our childhood. Every railway colony had monthly shows. And once a year, in winter, we’d have sports competitions—100-meter races, sack races, biscuit races. Prizes were given in the evening: maybe a pen, a soap case, or a box of chocolates. These may seem small now, but back then they felt magical. Those community gatherings, the joy of performing, of participating—they shaped my imagination and creative spirit.

The Railway Waziullah Institute in Chittagong, where my father served as elected General Secretary of the Railway Employees’ Club, became the heart of my early exposure to theatre. My mother would attend plays regularly, and I would go with her, holding onto the edge of her sari. I was the only son among four sisters, and I was pampered. That’s when the love for performance first took root.

I remember when I was around 10 years old, I teamed up with my friend. We built a stage ourselves, using planks and bedsheets, and staged a play. That was my first performance. Later, we did comedy sketches at people’s homes, small living-room acts, because we couldn’t get a chance on the main stage with the seniors. Eventually, in Class 10, I was cast in a proper production. After that, I continued acting through college and, eventually, after moving to Dhaka.

That little boy, holding his mother’s hand and watching theatre with wide eyes, has never really left me.

But I often say, my connection to theatre didn’t just come from the stage. It was born out of a certain environment—one filled with stories, community, and cultural resistance. Even the books I read—stories of Kolkata, rural Bengal, and a simpler, pre-industrial time—deepened that world for me. No roads, no buses, just long footpaths, palanquins, and bullock carts. Those images fed my imagination.

Later, after many decades, I returned to Murshidabad in 2012. It had been 56 years since I last visited. Standing in front of my family’s graves, I felt something shift inside me—grief, belonging, history. A sense that this land, too, was once mine. That people, in the name of politics and power, had drawn borders without knowing what they were taking from us.

Still, my heart belongs to the country where I grew up—this Bangladesh. This is where I lived my childhood, my youth, my adulthood. This land raised me. And in all of that, the railway institute in Chittagong was the first stage of my journey—quite literally. That little boy, holding his mother’s hand and watching the theatre with wide eyes, has never really left me.

You staged your own version of Tipu Sultan using household items as props. Do you think that kind of playful experimentation is missing from today’s polished productions?

The difference is quite significant. Today’s theatre productions are built with planning, purpose, and precision. There’s thought behind every element—stage design, lighting, set changes, everything. But back when I started, it was nothing like that.

As children watching those early plays, we sat right in the front row. I was the General Secretary’s son, after all, so I always had the best seat! What we saw on stage was very basic—just a curtain hanging at the back. And we copied that. We figured out how to hang a bedsheet with ropes so it could be pulled like a curtain. That was our first lesson in stage mechanics.

We used two tables and a chair—whatever we could find around the house. That was our set. It was all very improvised, very ‘deshi’. My uncle, who helped us, didn’t know anything about theatre either. But he was older and lived with us, so he guided us: “Say this line like this,” “deliver it that way.” We followed. The play itself wasn’t anything complex, but we did it. And that was the beginning.

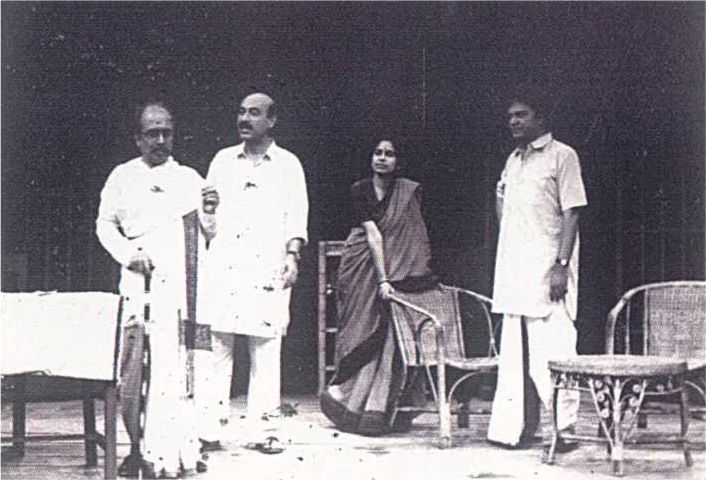

Later, when I joined Nagarik Natya Sampradaya as a founding member, things changed completely. That’s where I really learned what formal theatre means. Everything was methodical. First, the script was chosen. Then there would be a script reading. Roles were assigned, casting done, and responsibilities distributed. We would sit and plan the set—how the stage should look, how it should function. A scaled-down model of the set would be made, like a prototype. We rehearsed with that in mind. Every movement, every entry and exit, every prop—everything was accounted for.

This structured process came much later in my life. In my early days in Chittagong or even Dhaka, we just put up a curtain, placed two wooden boards to mimic a door, maybe cut a hole for a window—and that was our stage. It was raw but full of heart.

But once I entered formal theatre, it became either fully realistic or symbolically suggestive. The design, the performance, the blocking—everything had a reason behind it. And that continues even now. That’s the evolution I’ve witnessed—from instinctive, homespun creativity to disciplined, thoughtful theatre-making.

What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in the media industry since your first stage play?

I think the biggest change has been in the kind of content we create and the way we present it. The stories, the themes, the emotional crises we used to explore back then—those have evolved quite a bit. And so has our approach to staging them.

Take, for example, a classic like Oedipus. When we stage a play like that now, we don’t use realistic sets. We present it through a modern, conceptual lens—often using highly suggestive staging.

The old trend of building fully realistic sets—complete with doors, windows, walls—that’s largely faded. Today, we try to place more emphasis on the performance itself: the acting, the lighting, the sound design, the costumes. The goal is to pull the audience into the story so deeply that they forget about the mechanics of the stage—who opened which door, whether a curtain moved. We want them immersed in the world of the play.

Even in costumes, we now work with subtle shifts. A small change—like putting on a different hat—can signal a transformation in character. These are nuanced, thoughtful changes. I’d call them developments in thought—refinements that reflect a more evolved understanding of theatrical language.

And these aren’t random. We’ve been influenced by global theatre traditions, but we’ve also developed our own innovations. In fact, I’d say a new language of theatre has emerged in Bangladesh. And within that language, some very good work has been done. I feel proud to have witnessed—and contributed to—this evolution.

Your early work in plays like Oedipus on BTV introduced you to a national audience. Did you expect television to become such a defining platform in your career?

To be honest, no—I didn’t think at the time that acting would eventually become my profession. When I first performed in Oedipus on BTV, I didn’t imagine that television would shape the course of my entire career. But over time, I realized that if I truly wanted to sustain myself through acting, if I wanted to remain faithful to this passion, I had to take television seriously.

At that time, the kind of work I wanted to do—the plays I connected with emotionally and intellectually—was more possible on television than in Bengali cinema. The film industry back then was dominated by commercial productions, and most of them didn’t resonate with me. Television, on the other hand, offered more freedom. There were no commercial constraints. You could stage classic dramas, stories of ordinary homes, village life, our people, our country—stories rooted in reality and culture.

That’s what drew me in. Later, of course, out of financial need and circumstance, I also stepped into commercial cinema. I did some films. And then television itself changed. When “package dramas” began—sponsored, advertisement-driven productions—the whole dynamic shifted. Television dramas became commercial too. Plays started depending on brand funding, product placements, and viewership metrics.

And that’s where we are now. Nothing remains static. Everything changes. Even in theatre today, if you want to stage a production, you need a sponsor. And often, the sponsor wants creative input. They might dictate casting, themes, or even titles. This wasn’t the case in our time. Back then, the creative decision rested entirely with the director and the troupe. We chose what we wanted to say. And we said it.

But change is inevitable. We have to adapt to survive. I’ve accepted that. However—and this is very important—we cannot afford to forget the foundation laid by those who came before us.

Today’s television industry is fast-paced and commercial. What do you miss most about the earlier days of TV drama?

Of course, I miss those earlier days—and I’m not alone in that. Audiences still remember those plays, and they still long for them. People often say, ‘We wait for dramas like before.’ But the reality is, when they sit down today to watch something on TV, they often leave disappointed within five minutes. That says a lot. It shows the hunger is still there. The audience hasn’t moved on—they’re just not being offered the kind of storytelling that used to captivate them.

It’s not that we haven’t progressed. In fact, we’ve come a long way—technically speaking. Our industry now has skilled professionals who’ve studied film, production, sound, and lighting. Our artists are formally trained and very capable. Technicians are better equipped. Actors are more polished. On paper, everything looks fine.

But… and it’s a big but—there’s one crucial area where we’ve fallen behind. We’re moving away from our roots, from our own theatrical tradition, our cultural foundation. That soul, that depth that once existed in our stories, is being diluted.

Instead of nurturing what is truly ours, we’re looking outward too much. We’re imitating what we see elsewhere—trying to follow trends from other countries, often without understanding if they fit our social and emotional fabric. And in most cases, this shift is driven by advertising.

Everything now is tailored to attract sponsors or to go viral. And because of that, a kind of compromise has crept in. The storytelling suffers. The originality gets lost. And that’s what hurts the most. Not the change itself—because change is natural—but the way we are letting go of our essence in the name of progress.

So yes, I miss the honesty of earlier television dramas. I miss the stories that reflected our homes, our people, our laughter, our tears. That is what connected with the audience—and that is what they still crave, even if they can’t always articulate it.

You’ve worked with iconic directors like Humayun Ahmed and Abdullah Al Mamun. What was unique about their directing styles?

Both Humayun Ahmed and Abdullah Al Mamun had their own distinct styles—completely different from each other, yet equally powerful. Mamun Bhai directed in his own way, with a certain depth and seriousness. His writing was often rooted in social realism, with strong emotional undercurrents. On the other hand, Humayun Ahmed brought a kind of lyrical simplicity, a quiet magic to his work. His direction had a gentleness that felt intimate and familiar. But what united both of them was their deep connection to our cultural heritage.

“Humayun Ahmed brought a quiet magic. Mamun Bhai had depth and social realism. Both innovated, but never let go of our traditions.”

They never tried to reinvent the wheel by discarding our traditions. Rather, they innovated while embracing what was already ours. Their creativity was layered on a foundation of Bengali culture—its language, its values, its emotional landscape. They created something new, but never at the cost of what came before. That’s where their greatness lies.

Unfortunately, that mindset is increasingly rare today. What I see now is that many are trying to create something ‘modern’ or ‘fresh’ by completely breaking away from that foundation. And in doing so, they often lose relevance to our society. It’s like trying to build a house without a base.

Take language, for instance. Our Bengali—the language for which people gave their lives in 1952—is being distorted. A strange hybrid language has emerged, one that neither reflects proper standard Bengali nor respects our regional dialects. It’s being promoted as “natural Bengali,” but in truth, it isn’t natural at all. It feels artificial and disconnected.

I fully respect our regional languages and dialects. Every region has its own beautiful way of speaking, and that too is part of our mother tongue. I have no issue with that—ten districts can have ten kinds of spoken Bengali. That’s richness. But the standard Bengali language—shuddho bangla—should remain untouched when it comes to literature, television, and public discourse. That’s the core of our linguistic identity.

Humayun Ahmed and Abdullah Al Mamun understood this deeply. They didn’t dilute our language or culture for trends. They carried the past forward, and that’s what made their work timeless. That is what I value most about working with them—and that is what I fear we are gradually losing today.

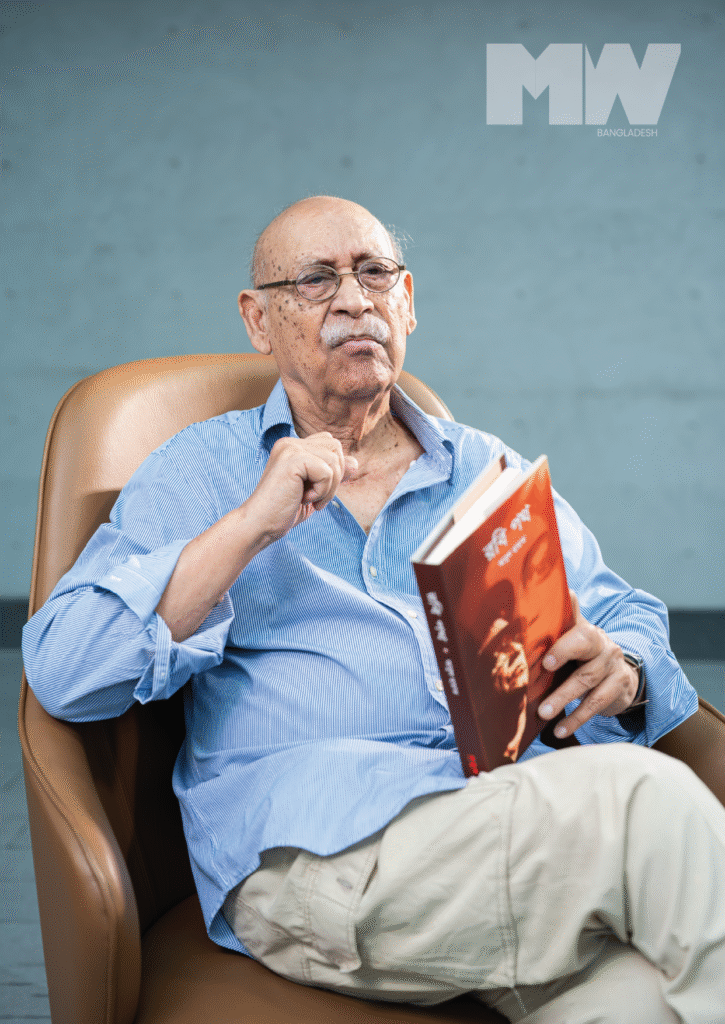

In your autobiography Robi Path, you returned to your childhood nickname ‘Robi’. What memories or parts of yourself did you reconnect with while writing the book?

I won’t say I was able to remember everything clearly. But I tried. You see, when you start writing about your life, it’s impossible to recall every single moment, every incident. If I tried to include it all, the book would have become too vast. Still, I gave it my best.

Whenever I couldn’t remember the sequence of certain events, I reached out—to my elders, the few who are still with us, to old friends, my wife, my sisters. They helped fill in the gaps. Because I’ve never been in the habit of keeping a diary, some things I just couldn’t piece together as accurately as I would’ve liked. But even so, I tried to be honest with the memories I did have.

That said, I don’t consider Robi Path to be anything spectacular. It’s not some grand literary achievement. But those who’ve read it—at least they didn’t say they were disappointed.

As for how writing and acting fulfill me… I think any creative work provides its own kind of joy. Acting pulls you into other people’s worlds. It’s external, performative. But writing—it’s something else entirely. Writing brings you back to yourself. It’s quiet. It reconnects you with your own voice, your own history.

How do acting and writing fulfill you differently?

For anyone engaged in creative work—whether it’s acting, writing, painting, or music—there’s one thing that’s certain: creation brings joy. Real joy. If you’re doing it with a heavy heart or without love, it loses meaning. The process itself must be joyful, but the sense of fulfillment you get after completing something—it’s even greater.

When I create a character in acting, it’s not something that just arrives from nowhere. I have to think about it. I have to imagine it. And that imagination, that ability to see a person who doesn’t exist yet—that’s the root of all acting. But imagination needs nourishment. It needs education. One must observe, read, feel. Without that, your imagination is empty. And without imagination, you cannot create.

The same goes for writing. Great writers always say, ‘You must read, you must study.’ I won’t claim that I’ve read extensively in a scholarly sense, but I’ve always had a love for books. I’ve read since my childhood—short stories, novels—and that passion eventually led me to write. Perhaps I could’ve read more, learned more, but life took its course. Still, the stories I carry inside me—those are not empty. They’re based on experience, emotion, and observation.

One big connection between acting and writing, for me, is people. I’ve always been a sociable person—just like my father. I love being around people. That constant interaction has helped me immensely in acting. Whenever I had to play a new character, I would think: Who does this remind me of? A man I once saw in a market? A relative? A neighbor? And I would bring that person to life on stage or screen.

And I do the same thing when I write. I draw from memory. I create characters based on people I’ve known, people I’ve watched, even people I’ve only passed by once but couldn’t forget. I think—how would this person speak? Which dialect? What setting suits their story? That’s why many of my stories are rooted in the world of railways. I was raised in railway quarters. Even now, when I see a train, I feel something stir in me. It’s not just nostalgia—it’s a connection, like the railway is still mine.

So, in the end, whether it’s acting or writing, the fulfillment comes from the same place: the joy of creating something out of nothing. I don’t see them as separate. To me, creation is creation—just in different forms. And I feel lucky that I get to do both.

Your first film, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, was with Ritwik Ghatak. What was it like to work with such a cinematic visionary so early on?

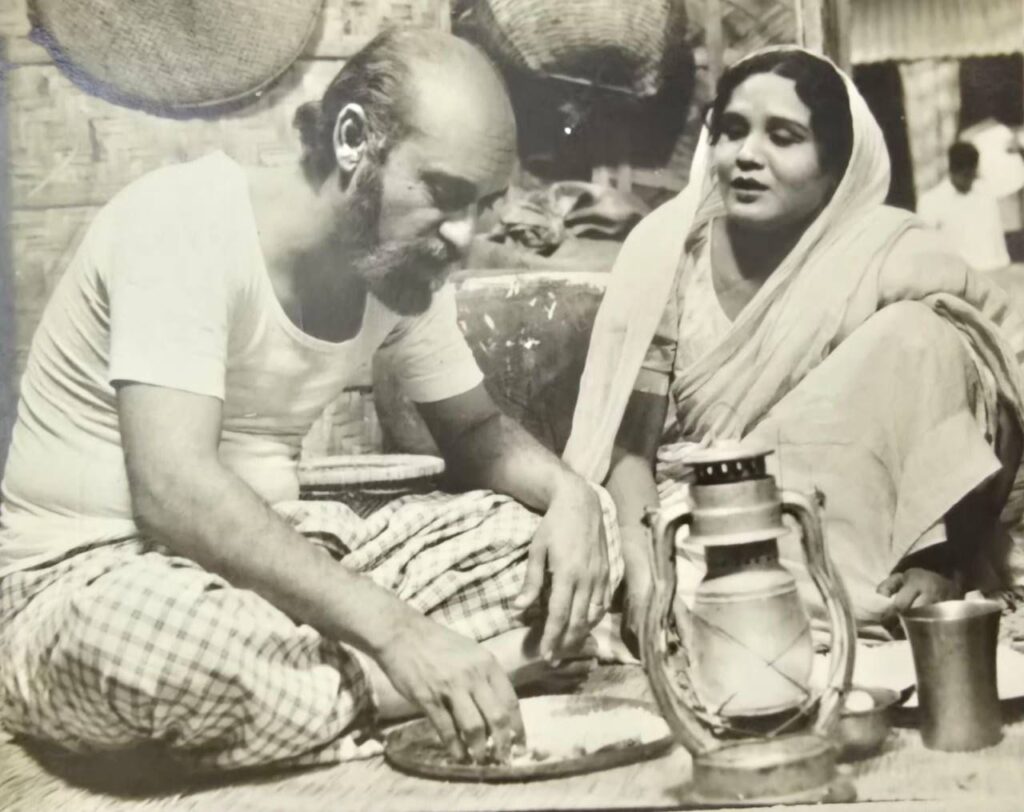

Titash Ekti Nadir Naam was the very first feature film of my life, and to begin that journey under the direction of someone like Ritwik Ghatak, was nothing short of a blessing. He was, and still is in my eyes, a cinematic visionary in the truest sense. When I heard he wanted me for the film, I was overjoyed. He had reached out to me through Syed Hasan Imam, and I didn’t hesitate for a second. I went straight to him and was selected for the role.

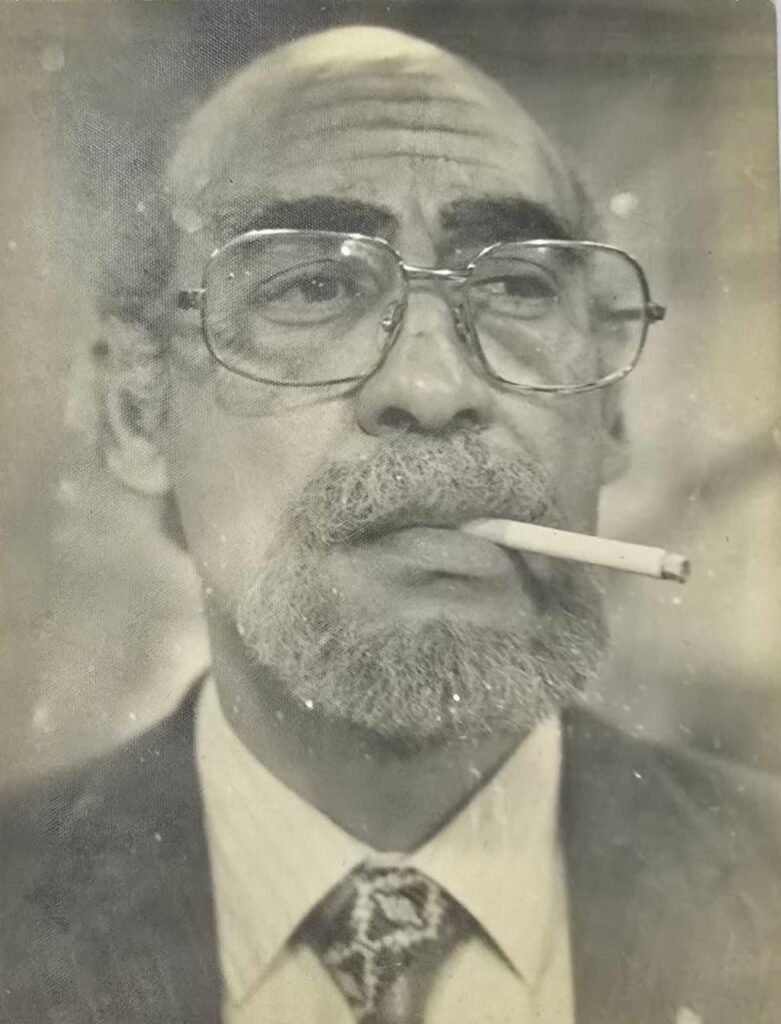

Now, before that, I had worked extensively in theatre. So, I had some understanding of what a director should be like—structured, composed, with a clear vision. But when I started working with Ritwik-da, I was completely taken aback. The man was extraordinarily disorganized. Chaotic, even. Papers lost, scripts misplaced. He would write scenes one day and forget where he’d kept them the next. Then, he would sit down right on the floor—literally on the shooting spot—take a hardboard, and rewrite the scene on the spot. And yet… the brilliance that flowed from that chaos was unforgettable.

I still remember how he would say, “Come, stand here. Move the camera there. Ready?”—calling out to one of his cameramen. It was as if the whole film was unfolding out of his head in real-time. And the extraordinary thing is—it worked. It more than worked. It created something timeless.

“To know that I was part of Titash Ekti Nadir Naam—that’s no small thing. It’s something I’ll carry with pride forever.”

With him, disorder became a kind of magic. I used to think—if someone forced him to work in a structured, formal way, he might lose the very spark that made his films so powerful. His genius didn’t follow traditional rules.

Today, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam is studied all over the world. It has become a textbook in film schools wherever cinema is taught. And to know that I was part of that film—it fills me with immense gratitude. To have been chosen by a master like Ghatak, in the very first film of my life—that’s no small thing. It’s something I’ll carry with pride forever.

Is there a daily ritual, something small you never skip, no matter how busy life gets?

To be honest, in this area, I’ve become a bit lazy. Not when it comes to acting—I’m always fully committed there. But with routines, especially health-related ones, I’ve struggled to maintain consistency. For example, there was a time when I was quite disciplined about walking. I had bought a treadmill, and every morning, I would walk for 40 to 45 minutes. That became a routine for me, especially after I crossed the age of 50.

Before that, I didn’t really need a specific fitness routine. My life was naturally active—I was constantly on the move. Driving, going to the office, running between theatre rehearsals, television shoots, film sets, and clubs. I even did the school and college drop-offs and pickups for my children. But after a certain point, my responsibilities began to lessen. The children grew up, my wife took on many of the daily responsibilities, and I realized I needed to stay active in a different way. That’s when the treadmill came in.

I even tried going to Ramna Park a few times, thinking I’d enjoy walking outdoors.

Unfortunately, after COVID-19, I stopped walking altogether. My health hasn’t been the same since. There’s another illness that I’ve been dealing with and it requires strict medication and lifestyle restrictions. Because of that, my energy and enthusiasm for walking have dwindled. The old zeal I once had is hard to find now.

Still, I know I should walk. My doctors tell me so. I tell myself so. I even managed to lose some weight at one point through great effort. And I do want to stay well—as long as I’m here, I want to be healthy. I’m about to turn 82. At this stage of life, I just want to preserve what I have and live the rest of my days with dignity and a little bit of strength.

What are you reading right now?

I’ve just started reading a book that I’m finding quite fascinating. It’s titled ’47-er Deshbhage: Gandhi o Jinnah—which translates to Gandhi and Jinnah in the Partition of ’47. It’s written by Serajul Islam Choudhury, one of our most respected scholars.

The book focuses on the roles of two towering political figures—Mahatma Gandhi and Mohammad Ali Jinnah—during the Partition of India in 1947.

What the book does beautifully is examine the birth of two nations—India and Pakistan—through the ideological clashes and personal journeys of Gandhi and Jinnah. I’ve only read about ten pages so far, but it’s already drawing me in. It’s the kind of book you want to return to whenever you have a quiet moment. Bit by bit, I’m making my way through it, and so far, it’s been an enriching read.

Many young people today are torn between practical careers and creative dreams—what would you say to someone standing at that crossroads?

Most people are dreamers. That’s something I firmly believe. Every human being carries dreams within them. And my father once told me something that’s stayed with me throughout my life: ‘Dream small dreams.’ It might sound simple, but there’s wisdom in it. If you set small, achievable goals, you’ll find that you succeed 99 percent of the time. You’ll face less frustration. And once you fulfill a small dream, you can dream a bigger one. But if you aim too high from the beginning, you risk being overwhelmed by failure and disappointment.

I’ve lived by that advice. I never dreamed excessively big dreams, nor did I live my life by a rigid plan or roadmap. Things happened organically. I wanted something—I worked towards it—and somehow, with the blessings of my parents, a bit of luck, and God’s grace, it happened.

But young people today are facing a different world. And the world is changing fast. So, if someone today wants to pursue a creative career, they must also be realistic.

So, when you decide to make the arts your profession, especially something like acting, you need to do it with full seriousness. That means studying the craft. You need training. You need to develop your imagination. If you don’t, you risk becoming repetitive—and the audience notices. They’ll say, “He does the same thing in every drama,” and just like that, your journey might stall.

But if you study, learn, read, and expand your creative world, you’ll have much more to give. You’ll rise on your own merit. You won’t need shortcuts.

And let me add this—media is not just about acting. This is something young people often misunderstand. Today’s creative field is broad and full of opportunities. You can become a director, a writer, a set designer, a lighting expert, a costume designer, or a sound planner. There’s immense demand in all of these areas. In our early days, we did everything ourselves—set design, lights, sound cues. But now, the media has become specialized. Each area has its own experts. So don’t limit yourself. Explore.

The field itself has expanded—TV dramas, advertisements, films, OTT platforms—all of it is part of the same ecosystem. If you want to enter, come prepared. Learn the language of the craft. That way, whether it’s film or OTT, drama or commercial work, you’ll know what to do. Skill will set you apart.

And of course, there are the other essentials: discipline, dedication, accountability—to your craft, your colleagues, your audience, and your country. These are not just clichés. In group theatre, we were taught to be on time, to rehearse seriously, and to take responsibility for our roles. That mindset builds lasting artists.

But when someone enters without learning—maybe they’re naturally talented, maybe they get quick fame—what often follows is ego. And ego creates distance, even conflict, between generations. That’s never healthy. Because the older generation laid the foundation. You can’t build a superstructure while ignoring or disrespecting that base. If you try, the whole thing will collapse.

After everything you’ve experienced – as an actor, engineer, writer, and citizen – what do you hope people will remember most about you?

If I’m being honest, I think I’ve been accepted and recognized most widely as an actor. That’s where people know me best. My writing—while meaningful to me—hasn’t reached as many people. I’ve written columns, yes. For a time, I had a regular column in Prothom Alo.

But still, I don’t call myself a writer. I’ve never felt that title fits me. Writing has always been a personal pursuit, something I’ve done for pleasure—for the joy of it. Even now, I write out of habit and interest, not for prestige or position. So, I hesitate to claim the word “writer” for myself, though I do write, and will likely continue to.

But if there’s one identity I do fully embrace, it’s that of an actor. That’s what I am. And I would also say I’m a director, particularly in the world of television and video media. That’s another part of my professional life that I value deeply.

So, if people remember me, I hope it’s as an actor who gave his best and as a director who cared about his work. Those are the roles I hold closest. The rest—engineering, writing, even citizenship—are important chapters of my life, but acting and directing form the heart of it. That’s the part I hope people will remember.

“The older generation laid the foundation. You can’t build a superstructure by ignoring or disrespecting that base.”

Fashion Direction & Styling: Mahmudul Hasan Mukul

Photographer: Mobarak Faisal

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman