By Abak Hussain

When director Richard Matheson took on the ambitious movie project Somewhere in Time (1980), he knew he needed to find a location that looked like it hadn’t changed in about a century. Today, special effects and green screens can create entire worlds as backdrops pretty cheaply, but this was 1979, and an ambitious Matheson, working with the hottest star in Hollywood – a young Christopher Reeve fresh off the success of the first Superman (1978) – knew the location had to look and feel right.

The director didn’t want to recreate it all on a Hollywood lot, like so many period films did. This was a time travel movie, and he wanted to film in a town which really had horse-drawn carriages on the streets and very little if any sign of modern technology.

The island of Mackinac came to the rescue – it was in this car-free Michigan island that the movie was shot, and though the film flopped critically and commercially (so much for Reeve’s desire to break out of that Superman-typecasting), the location remains a thing of intrigue. Even now, 45 years after that movie came out, one can go to Mackinac and feel transported back to the early-1900s. Michigan has long been a global car-manufacturing hub, but in Mackinac you won’t find any. It’s still all horses, and the refreshing absence of carbon monoxide in the air serves up to visitors a poignant reminder of what has perhaps gotten lost in the relentless march of progress.

Not even Teslas – with the company’s dark history of greenwashing and hidden environmental costs – are in the end good for the Earth, and by now most people know that not a word out of Elon Musk’s mouth can be trusted. Needless to say, the electric car revolution has left the people of Mackinac totally unimpressed, and the island’s ways remain unchanged.

Photo Source: Axel Richter

Mackinac has a human population of about 600, and a horse population also of 600. The highway that loops around the island is the only US highway without cars. The only way to get around the island is by foot, horse, or bike. It would be a mistake though, to assume that Mackinac residents are totally against change – other technological innovations certainly do exist, and certainly many of them frequently travel to more mainstream parts of the country and the world, enjoying electric cars and maglev trains, but they always, I imagine, relish coming home to the calm air and the soothing clip-clop of hooves.

They do not fear or misunderstand technology, they simply exercise greater control over what they want in their lives, and resist going with the flow. From the people of Mackinac, to the Amish community, to various isolated groups that live tucked away in the Amazon, there exist, to this day, plenty of people who look at the modern world and say: no thanks.

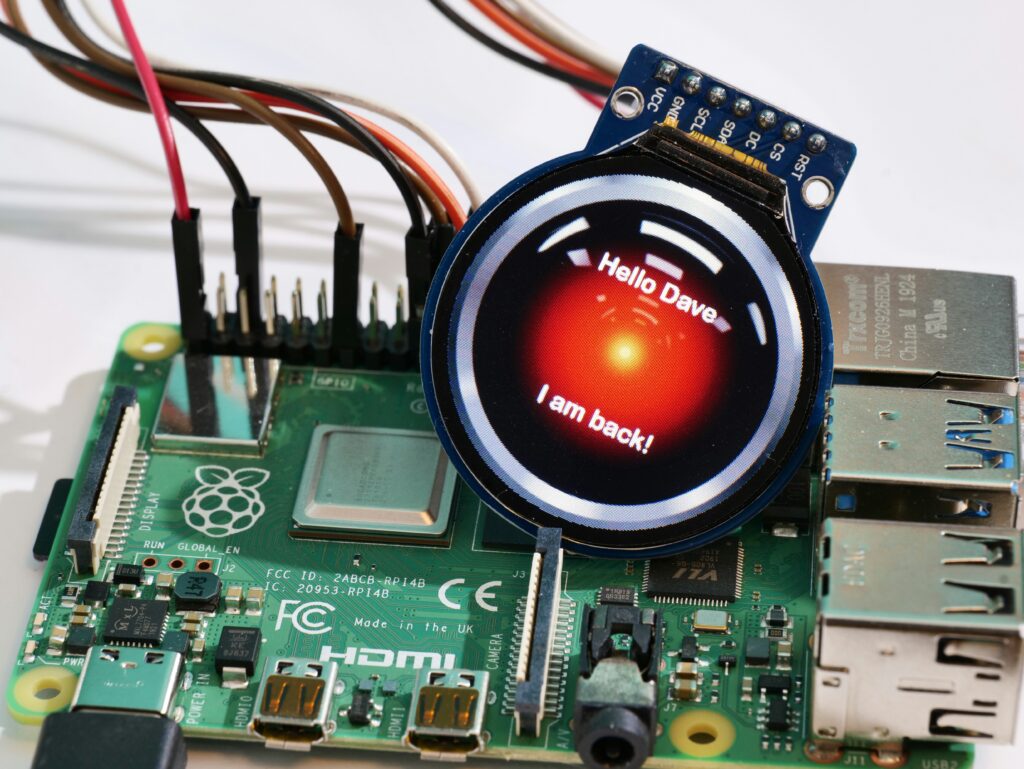

Progress on auto mode

Let me at this point let my thoughts wander for a bit: I don’t really want to get into a this-versus-that type debate about the value of technological progress. If there is one thing about human civilization that is certain it is that tech will move forward and we are hapless in the face of it. Ever since our ape ancestors learnt that beating enemies to death with a bone a la Kubrick’s 2001 was more efficient than using hands, mankind in its unstoppable ingenuity jumped on the superhighway of making tools – things that make life easier. And then more and more tools, which themselves go on to make more and more tools. And here we jump cut Kubrick-style to deep space fantasies and AI villains that are smarter than us. The pace of change is enough to send an existential chill through most people’s spines. From Luddites, to the Catholic Church, to ultraconservative governments and religious communities around the world, many have tried to stop the forward-movement of progress, and at most they have succeeded in slowing down the march, but never stopping it altogether.

Because of its exponential nature, the rate of progress also quickens up, like a rapidly heating saucepan. This causes centuries of innovation to collapse into mere decades, and then into years. These changes are also being normalized into our lives at a frightening speed: just a couple of years ago, no one had heard of ChatGPT, and if you had told them, it would have sounded like pure sci-fi. Now, it’s already old, ubiquitous, almost boring, spawning a countermovement of self-help gurus shouting: “if you’re only using ChatGPT, you are getting left behind! Here are 5 other …” and so on.

The pace is utterly disorienting, and entirely unprecedented in the history of our species. Everyone acts like an expert, like they know where all of this is heading, but the truth is most people are just winging it. Will AI lift us up, abolish work, and make life prosperous for all? Or will it bring about another hellish dystopia? I don’t have a clue, but the widespread misery and inequality we see in the world even after the most glorious wealth-creation makes it hard to be optimistic. For sure, those with jobs high up in the tech ladder will be rich for a while. How others will fare is hard to tell. I find it hard to care about Sam Altman’s net worth.

Recently, I was a speaking at a panel in the city about creative writing – craft, style, that sort of thing. In the Q&A portion, one participant asked a question I had been dreading: “What do you think is the future of creative writing, now that AI can generate writing for us.” Feeling a little deflated, I frankly talked through my personal thoughts and feelings on AI, without much of an urge defend the value of writing done by humans, which I feel deeply in bones. Until recently, it felt like the tech discussion was mostly located in the realm of machinery, efficiency, transportation, robotics – all the manual labor or drudgery that tech can take off our hands so that humans are freed up to be humans. I’m all for cars instead of horses, electric cars instead of gas-guzzlers, better software and smarter smartphones and an interconnected world and financial system. But technology encroaching into the creative space leaves me cold, be it in art, or in writing, or in journalism that smells like the work of an algorithm. Maybe because I’m a writer it feels so personal, and at long last I am face to face with an anxiety that people in other professions have felt for a long time.

And so I now understand better why we sometimes step off the carousel, and we dream. We stop and breathe to avoid the motion sickness. Some communities go back to their analogue roots, re-connect with the earth, some individuals go on digital detoxes or vow not to use AI. Some proudly reclaim the term Luddite, a pejorative applied to anyone apparently too stupid to realize that progress cannot be stopped, as though even beginning to question a Black Mirror-style turn of things is the same as destroying textile machinery, or opposing the discovery of fire or the invention of the wheel.

But just as holding on to the past will doom us, uncritically jumping onto every smart innovation championed by technocrats also may not be the smart thing to do. We can certainly progress in human dimensions, emotionally and spiritually, in paths untouched by tech titans. And so, like Christopher Reeve’s character in Somewhere in Time,we just might fall in love with a time that is lost forever. Like the proud residents of Mackinac, in our own domains, we just might be able to bring back – or preserve – a version of things that was better for the soul, for our lungs, for the health of the planet.

Abak Hussain is Contributing Editor at MW Bangladesh.

Feature Image By Steve Johnson

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman

- mahjabin rahman